In Vitro Bactericidal Activity of An Environmentally Isolated Phage Cocktail Against a Characterized Recombinant Endolysin Lysecd7 on Clinical Bacterial Isolates

Idah Sithole-Niang* and Tawanda Ashley Chari

Department of Biotechnology and Biochemistry, University of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe

Submission: November 2, 2022; Published: November 28, 2022

*Corresponding author: Idah Sithole-Niang, Department of Biotechnology and Biochemistry, University of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe

How to cite this article: Idah Sithole-N, Tawanda Ashley C. In Vitro Bactericidal Activity of An Environmentally Isolated Phage Cocktail Against a Characterized Recombinant Endolysin Lysecd7 on Clinical Bacterial Isolates. Curr Trends Biomedical Eng & Biosci. 2022; 21(1): 556055. DOI:10.19080/CTBEB.2022.21.556055

Abstract

Background: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is rapidly spreading, which is pushing humanity into a “post-antibiotic era” where most antibiotics are no longer effective. Scientists are researching bacteriophages as a potential therapy against ESKAPE pathogens, which are a problem in hospital settings, as a result of the development of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. This study assessed the antibacterial efficacy of recombinant LysECD7 and environmental bacteriophage cocktail on bacterial isolates.

Materials and Methods: Environmental water and soil samples were examined for the presence of bacteriophages that were capable of killing the bacteria Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterobacter cloacae. Utilizing environmental isolates, a bacteriophage cocktail was created and its ability to effectively lyse bacterial growth cultures in vitro was examined. A synthetically generated Myoviridae lytic enzyme named LysECD7 was cloned, produced, and demonstrated wide bactericidal efficacy against gram-negative bacterial pathogens. The bacteriophage cocktail and endolysin’s (0.203mg/ml) antibacterial activity were assessed using a spot assay and an antibacterial activity assay in broth culture. Phage and endolysin bacteria samples were taken and their OD600 levels were checked every 30 minutes for phages and every 30 seconds for endolysin.

Results: The average antibacterial activity of isolated bacteriophages was 43.58%, as opposed to the recombinant endolysin’s 31.48%. Bacterial absorbance declined steadily with each subsequent phage replication cycle, however, after six hours, there was a minor improvement in bacterial growth. The Gram-negative E. coli ATCC 25922 and E. cloacae NCTC 134565 exhibited the highest activity for both treatments, while the S. aureus and P. aeruginosa had the lowest activity.

Conclusion: A single dose of low endolysin concentration had a very significant antibacterial activity, bacteriophage treatment of bacterial isolates varied greatly per each species under the same conditions. Under the same circumstances, bacteriophage and endolysin activity change within bacterial isolates, demonstrating that activity is independent of concentration. Lysin activity was highest in E. coli and lowest in the other bacterial species, but it should be emphasized that lysin and bacteriophage activity and efficacy differ with each treatment.f

Background

The ESKAPE group of pathogens, which can cause bacteremia, pneumonia, etc., has repeatedly shown itself to be one of the main offenders among superbugs [1,2]. According to Antonova et al. [1], the ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other Enterobacteriaceae species) group of pathogens require a lot of antibiotics due to the rapid spread of multiple drug-resistant bacteria. Due to selection pressure, some bacteria interact through quorum sensing to adapt and gain resistance genes from other members, especially in a biofilm. AMR is a natural process [3,4]. Due to the lack of pipelines for developing new antibiotics and the global spread of AMR bacteria, there is a need to investigate alternate medicines. Bacteriophage therapy, which uses phages with an obligatory lytic cycle, is one such treatment. In addition to antibiotics, bacteriophage therapy is an effective method of treating bacterial infections [5]. Long before penicillin (“the wonder medicine”) was invented, phages were used to control microbial populations, but after antibiotics were discovered, research and development on their effective use came to an end. Bacteriophages have co-evolved with bacterial species and have helped to select and evolve microorganisms that are better suited to reducing infection [1,6,7]. The co-evolution of microbial genetics with bacteria has significantly shifted bacterial populations to only species better able to fend off illnesses and endure throughout time.

Endolysin, holin, and other phage-encoded lytic proteins help break down the bacterial membrane by cleaving the cells’ peptidoglycan layer, which causes cell death and releases phage partic [8,9]. Today, three different types of phages can be studied: prophage mining and phage sequences embedded in bacterial genomes [10-13]; individual laboratory isolates infecting a single specific bacterial species [14-16]; viral metagenomics of populations harvested in large quantities from the environment [17-19]. The growth of phage-resistant bacterial species, however, also leads to the emergence of antimicrobial-susceptible bacterial species, providing a pathway for phage-encoded endolysins [20- 23]. Bacteriophages have always had an impact on the microbial population, regulating the number of microbes on earth [24,25]. In numerous infectious model organisms, bacteriophage lysins, a group of highly developed peptidoglycan hydrolases, have proven to be effective enzyme antibiotics (enzybiotics). Because of their structure, it is possible to create bioengineered lytic enzymes with desired characteristics, such as increased activity or a wider killing spectrum [14,26].

Additionally, unlike bacteriophage lysins, designed lysins can “lyse from without” (LO) after being applied to the target bacteria externally [27]. The phenomena that occur when the phage lysin kills cells after being applied outside of the cellular matrix are described in LO. Endolysin offers a distinct class of enzybiotics that are potent and easily accessible in this era of rising AMR to combat AMR infections.

The study’s objective was to investigate the dynamics of success while using bacteriophages and endolysin in place of conventional antibiotics. To demonstrate this, LysECD7 and an environmental cocktail of bacteriophages were tested in antimicrobial assays against clinical bacterial isolates that acted as representative members of the ESKAPE group of pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Collection and sample preparation

On either side of the bridge along Simon Mazorodze Road (-17.9814, 30.9624), water samples from the Hunyani River were taken using a 1-liter bottle. Lake Chivero, from which the City of Harare receives some of its water, is where the Hunyani River sips. Five meters from the banks of a tiny creek that flows through the University of Zimbabwe, soil samples were also taken.

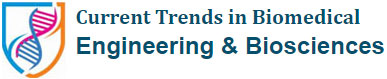

The liquid samples were processed as a crude lysate, and 5ml of the mixture was combined with 50ml of bacteria (in log phase with an OD600 of 0.6), and the mixture was then cultured at 37 oC in a shaking incubator at 150rpm for 12 hours. To completely loosen the particles in solid samples, 50ml of LB broth was added to each 5g of the sample before being shaken at 200rpm for 30 minutes. After the flask had stood for two hours, the supernatant was added to a bacterial suspension, and it was incubated. The culture was transferred into 50ml falcon tubes after incubation and centrifuged at 4000g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. A 10 ml syringe was used to draw the supernatant, and it was filtered using a 0.4μm filter membrane. Figure 1 depicts the whole experimental design (Figure 1).

Preparation of bacteria

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus 25923, Enterobacter cloacae NCTC 13465, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa 2751 were used in this investigation as clinical bacterial isolates from Zimbabwe’s National Microbiology Reference Laboratory. Bacteria were introduced into a 50ml tube of sterile, rich NZCYM medium. The tube was then cultured overnight at 37 °C with mild agitation at 200 cycles per minute. The bacterial culture was centrifuged at 5000 g for 5 minutes at 4 °C, and the pellet was resuspended in 20ml of sterile 0.01M MgSO4 after the supernatant was discarded. The tubes were incubated at 37 oC for an hour with gentle agitation, and they were put into storage at 4 °C (cells will be viable for at least 4 weeks without loss of viability).

Bacteriophage isolation and purification

A modified version of Adams, (1959) approach was used to analyze the bacteriophage lysate. After combining 0.25ml of the phage culture with 1 ml of logarithmic phase cells (OD600 = 0.5 - 0.6) of the host bacterial strains in LB broth supplemented with 0.1M CaCl2, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C in a shaking incubator for 20 minutes. Following incubation, 3ml of 0.7% agarose was aliquoted into the tube, properly mixed, and then poured as an overlay onto already-set agar plates (incubated at 37 °C for 12 hours). The bacteriophages were purified by selecting a single plaque from the initial test plate, inoculating it into a 5 ml culture of the host bacteria in LB broth supplemented with 0.1M CaCl2, and incubating it for 10 -12 hours at 37 °C with minimal agitation. The inoculating loop was then sterilized in alcohol and flamed. A 0.22μm membrane filter was used to filter the liquid culture after it had been centrifuged at 10,000g in a microcentrifuge and added to an SM phage buffer. For 20 cycles, the isolation and reinfection phases were repeated.

Maintenance and storage of bacteriophages

Phages were stored long-term using two different methods: directly at 4 °C and as glycerol stocks. After purification, a phage lysate was obtained. It was kept in sterile 2ml Eppendorf tubes and kept at 4 °C until it was needed. A glycerol stock with a final concentration of between 15-20% was achieved by combining 600μl of the filtered phage lysate with 400μl of 50% glycerol, then freezing the combination at -80 °C until use.

Molecular characterization of isolated bacteriophages

16S ribosomal RNA polymerase chain reaction

Bacteriophage DNA extraction was then carried out using an Invitrogen kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was amplified using the 16S universal primers (Eurofins) 1492R: 5’CGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT3’ and 27F: 5’AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG3’ in a 16S ribosomal RNA polymerase chain reaction. The PCR amplification protocol used in the thermal cycler is as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 60 s, and 72 °C for 2 minutes, and then a final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes. The reaction’s byproducts were run on an electrophoresis gel stained with ethidium bromide.

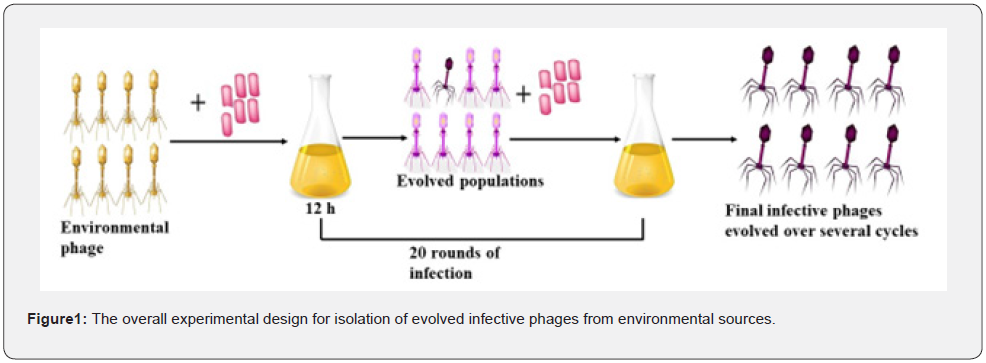

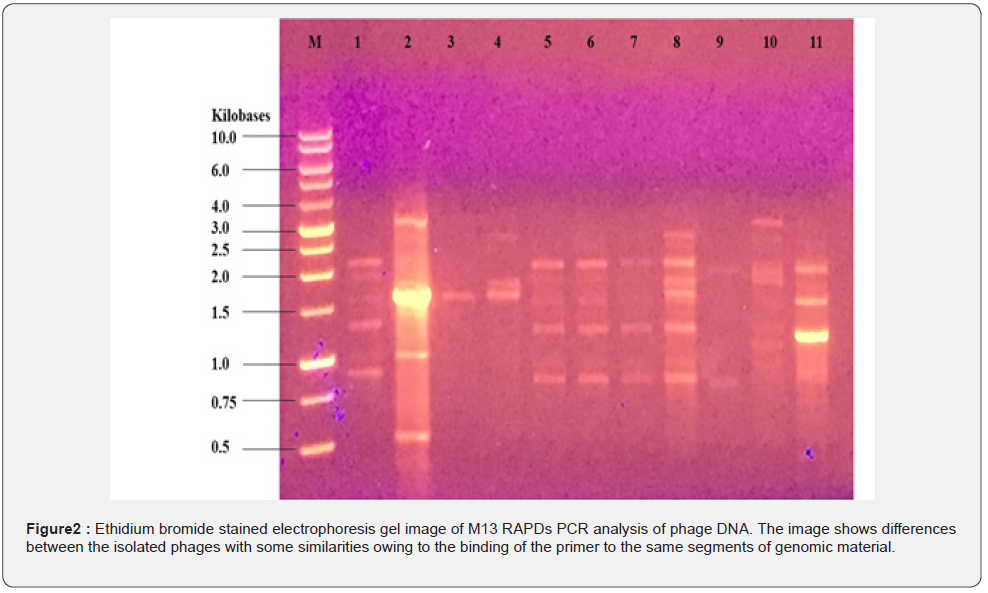

Phylogenetic analysis using M13 RAPDs polymerase chain reaction

Utilizing the M13 F primer, the RAPDs analysis was performed on the extracted viral genetic material. The thermal cycler was used to perform PCR amplification using the M13 F primer, 5’GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC3’. The amplification protocol used was: initial denaturation at 95 oC for 90 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 36 oC for 60 s, and 72 °C for 2min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10min. With the help of DendroUPGMA: Dendrogram construction using the UPGMA algorithm (urv.cat), the 100 bootstraps duplicating the test, and the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean, the bands were scored appropriately and used to draw a phylogenetic tree.

Bacteriophage cocktail preparation

A phage cocktail, which had at least 4 separate bacteriophages, was created by mixing the bacteriophages that showed a wide lytic spectrum across the bacterial species and were unique from one another. To create the bacteriophage cocktails, the bacteriophages were given numbers, and the numbers were chosen at random without replacement.

Construction of the Cloning Vector pUC57-LysECD7- Amp

Using the accession number ASJ80195.1, Antonova et al. [1] sequenced the endolysin gene and acquired the mature endolysin gene sequence (peptidoglycan L-alanyl-D-glutamate endopeptidase [Escherichia phage ECD7]). The immediate 5’ and 3’ of the endolysin gene, respectively, were supplemented with restriction endonuclease sites for BamHI and HindIII. Using Snape Gene software, the restriction site modified gene was in silico cloned into pUC57-Amp at the EcoRV restriction site and assessed. GeneWiz synthesized the modified gene, which was then sub-cloned into pUC57-Amp at the EcoRV restriction site.

Transformation of pUC57-LysECD7-Amp and subsequent in vivo cloning of the gene

According to the procedure described by Sambrook et al. [28], the generated plasmid containing the LysECD7 gene was transformed into E. coli NM522 cells. On the ice, 100μl of chemically competent cells from -80 °C were defrosted in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube. The frozen cells were mixed with approximately 10 μl of the pUC57-Amp- LysECD7 plasmid DNA and incubated on ice for 30 minutes. The cells were placed in a water bath and subjected to a 90-second heat shock at 42 °C before being immediately returned to the ice with 400 μl of LB broth. The cells were then agitated at 180 rpm for 1 hour while being incubated at 37 °C. Cells were divided into 200 and 100μl aliquots and plated out onto LB agar plates treated with ampicillin. The cells were then incubated overnight at 37 °C. To confirm the presence of the recombinant endolysin insert in randomly chosen colonies, colony PCR was carried out using primers that were unique to the insert. Colony PCR was performed as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 oC for 60 s, and 72 °C for 2 minutes, and then a final extension at 72 °C for 10 minutes. The reaction’s byproducts were run on an electrophoresis gel stained with ethidium bromide.

Plasmid Extraction by Alkaline Lysis Method

Striking positive clones on ampicillin-containing LB agar was done. A single colony was selected from each plate and injected into 1ml of ampicillin-supplemented LB broth. The culture was incubated at 37 °C with agitation at 180rpm. Using UV/Vis Spectrophotometry, the cell culture was developed and monitored until it attained an optical density of 0.4 units at 660nm. By using the alkaline lysis technique as described by Sambrook et al. [28], plasmid DNA was extracted from the overnight culture.

Restriction Digest and Cloning into Pdawn

The products of the colony PCR were cleaned and double-digested using BamHI and HindIII enzymes. A light-inducible plasmid, pDAWN, was isolated using the alkaline lysis method [28], and digested using the enzymes BamHI and HindIII in a total volume of 50μl (10μl of DNA, 5μl of NEB Buffer 3.1, 1 μl BamHI, 1μl HindIII, 33μl of ultra-pure water). The digestion mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour and run on an agarose gel to confirm digestion. After complete digestion of the DNAs, the vector (pDAWN) was mixed with the insert (LysECD7), at a ratio of 1:7 respectively forming a ligation mixture. To the ligation mixture, 1μl of T4 DNA ligase, and 2μl of ligation buffer with ATP and water were added to a microfuge tube. The ligation mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 hours and ligation was confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli NM522 cells according to the transformation protocol by Sambrook et al. [28].

Recombinant Protein Isolation

Escherichia coli NM522 cells were cultured in 100ml of LB broth supplemented with kanamycin at 37 °C while being shaken at 200rpm for 3.5 hours in the dark. Induction was then achieved by exposing the broth culture to light at 20 °C for 16 to 24 hours. Using a Japson Benchtop centrifuge, the cells were centrifuged at 5,000g for 30min at 4 °C before being re-suspended in 200l of 20mM Tris HCl, 250mM NaCl, 0.1mM EDTA, pH 8.0, and 100g/ml of lysozyme. The tubes were sonicated after being combined with 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (30 s pulses for 5 minutes), and incubated for 30 minutes at 25 °C. Extracellular debris was eliminated by centrifuging the supernatant at 10,000g for 30min in a microcentrifuge and filtering twice through a 0.22μm filter.

The filtrate was mixed with 1mM imidazole and 50mM MgCl2 before being placed onto a column that had already been preequilibrated with 20mM Tris HCl, 250mM NaCl, and 50mM imidazole, pH 8.0. The fractions were eluted using a G50 Sephadex column and collected using a fraction collector. The collected protein fractions were dialyzed against 20 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5. Protein concentrations were measured using a spectrophotometer at 280nm.

Antibacterial Activity of Isolated Endolysin

The strains for the tests of antibacterial activity were taken from clinical isolates of various bacterial species. To swiftly assess the effectiveness of the recombinant endolytic protein on stationary phase cells on an LB-Agar plate, a spot test was used for the first assay. For the recombinant protein, 1μl of diluted concentrations of 25, 50, 100, and 200μg/ml were added to each quadrant of the plate that had previously been covered with a bacterial culture. The plates were set for 30 minutes at ambient temperature, to allow the endolysin to diffuse into the agar. After that, it was inverted and incubated for a further night at 37 °C. The second test involved adding endolysin to a bacterial culture that was being grown in LB broth. 100ml of LB broth and 1ml of an overnight bacterial culture were combined, and the mixture grew to the exponential phase (OD600 = 0.6). 100ml of the bacterial culture and 100 μl of the expressed endolysin were combined in a 500ml flask. PBS buffer devoid of endolysin served as the negative control. The recombinant endolysin’s antibacterial activity was measured by plating 100μl from each culture after the initial absorbance reading while the mixes were incubated at 37 °C with agitation and examined for changes in absorbance values every half minute. Following is an expression of the antibacterial activity calculated at T = 30 seconds: Recombinant endolysin activity (%) = 100% - (CFUexp/CFUcont) × 100%, where CFUexp is the number of bacterial colonies in the experimental culture plates, and CFUcont is the number of bacterial colonies in the control culture plate.

Antibacterial Activity of Isolated Bacteriophage

The strains for the tests of antibacterial activity were taken from clinical isolates of various bacterial species. To promptly assess the effectiveness of the phage cocktail on stationary phase cells on an LB-Agar plate, a spot test was used for the first assay. Approximately 1ml of the phage cocktail from the original culture was diluted to 10-4, 10-6, 10-8, and 10-10 before being added to each quadrant of an LB-agar plate that had already been spread with a single clinical isolate of bacteria. The plates were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature so that the phage cocktail could diffuse into the media, turned over, and incubated for an additional 12 hours at 37 °C. For the second test, 100ml of LB broth and 1ml of an overnight bacterial culture were combined, and the mixture was allowed to grow to the exponential phase (OD600 = 0.6). 500ml flasks were filled with a mixture of 100ml of the bacterial culture and 1ml of the isolated bacteriophage cocktail (including at least one phage infecting each type of bacteria), with PBS buffer devoid of bacteriophage serving as the negative control. To determine the antibacterial activity of the bacteriophage cocktail, the mixtures were incubated at 37 °C with agitation and monitored for any change in absorbance values every 30 minutes at OD600 and 100μl from each culture plated after the first absorbance reading. Bacteriophage cocktail antibacterial activity was calculated as follows: Bacteriophage antibacterial activity (%) = 100% – (CFUexp/CFUcont) × 100%, where CFUexp is the number of bacterial colonies in the experimental culture plates, and CFUcont is the number of bacterial colonies in the control culture plate.

Results

Isolation of Bacteriophages

Only 38 of the bacteriophage isolates survived through the second phase of bacterial plating, out of a total of 120 isolates that were detected and selected from the first round of plating from the environmental sources. The 16S ribosomal RNA gene was examined in the bacteriophages that had survived the second infection cycle, and any that had it were not employed in subsequent infections. As shown in Figure 1, the 16S rRNA analysis eliminated a total of 27 phages, which were then employed for the remaining infection rounds and described using the RAPDs PCR technique to check for genetic diversity in the isolates. When seen under UV, the phage isolates displayed varying levels of heterogeneity.

To visually examine the genetic variations between the environmental phage isolates, a phylogenetic tree was drawn using dendro UPGMA using the RAPDS-PCR electrophoresis gel for scoring phage genome diversity (Figure 2). The selection of phages from various lineages to create the mixture utilized for assessing bactericidal activity was then done using the phylogenetic tree.

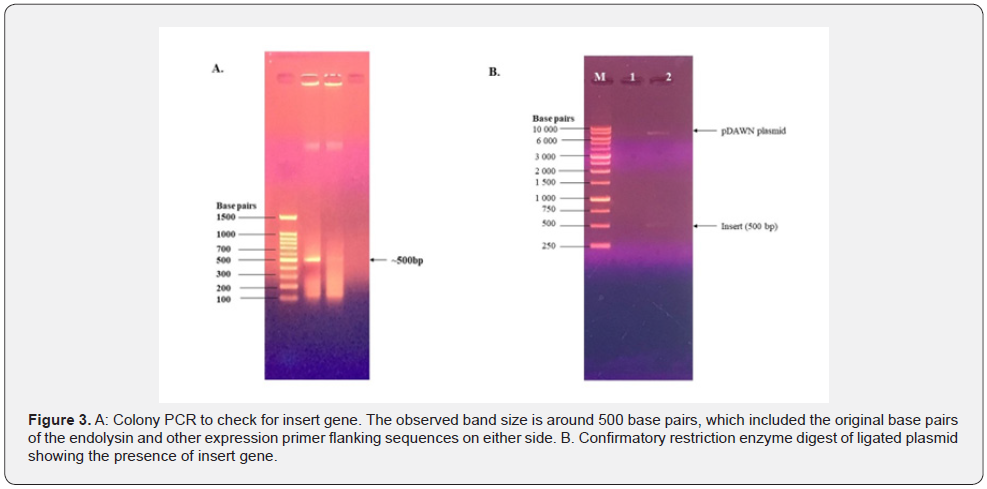

Recombinant Expression and Purification of LysECD7

Bacteriophage lysin, LysECD7, synthetically cloned into pUC57-Amp and transformed into chemically competent E. coli NM522 cells. After overnight incubation at 37 °C, cell growth was seen on LB agar plates supplemented with 50 μl of ampicillin diluted to a final concentration of 20μg/ml. Colony PCR was used to confirm the insert (Figure 3A), and the LysECD7 was ligated for expression in the pDAWN plasmid and a confirmatory plasmid extraction was done after digestion of the pDAWN plasmid with BamHI and HindIII enzymes (Figure 3B).

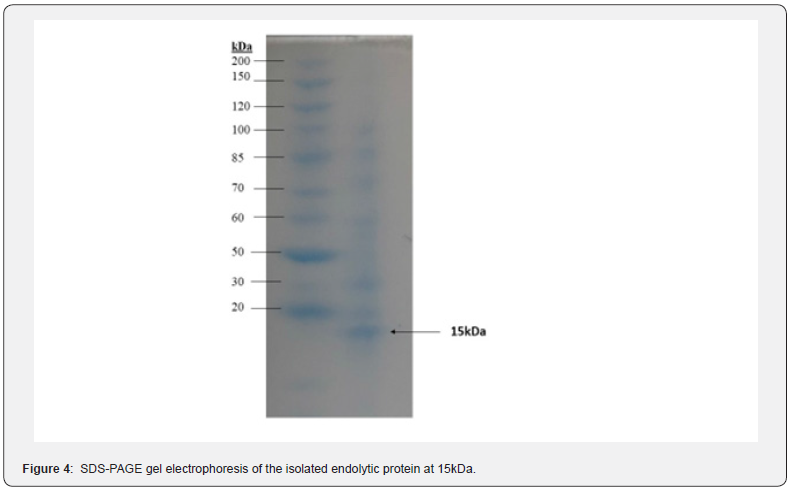

The inducted E. coli cells were sonicated to extract the recombinant protein from the cells. The extract was filtered with a 0.22 μm filter membrane and run on SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis to confirm the presence of the protein, LysECD7 (Figure 4).

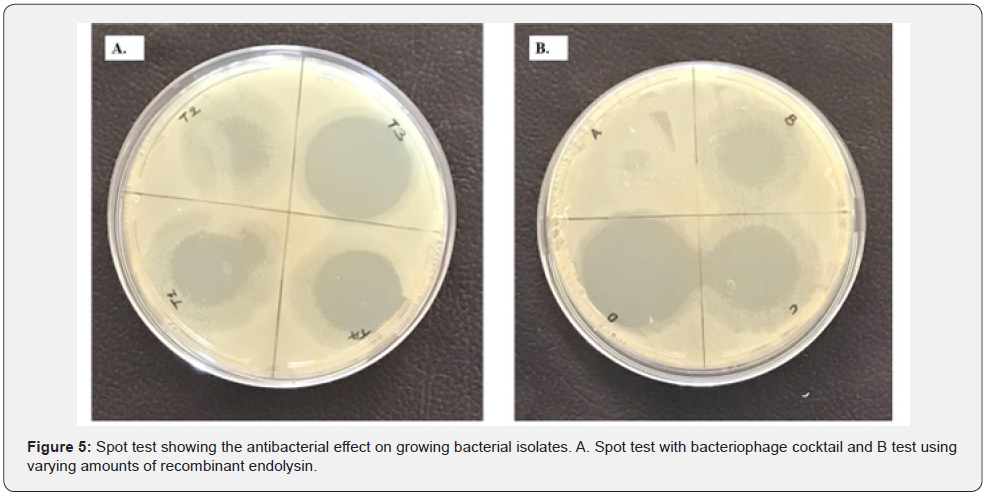

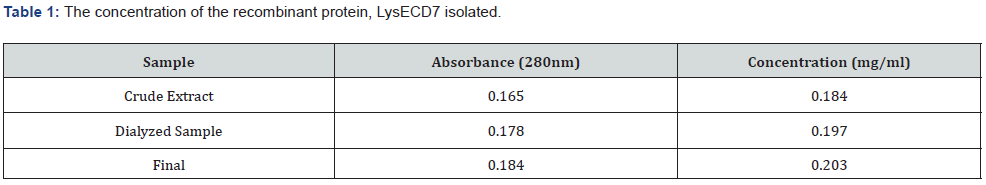

The crude protein was dialyzed three times in a water bath containing 20mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), and the dialyzed fraction’s absorbance was compared with a Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) standard to determine its concentration. The dialyzed sample was additionally concentrated using a speed-vac concentrator to produce the final stock, which is represented in Table 1 as being 0.203mg/ml (200μg/ml). Using a combination of spot tests and an antibacterial assay for activity determination of LysECD7, the extracted lysin sample was put through in vitro testing on bacterial isolates in the same way that bacteriophages from the environment were (Figure 5).

Antibacterial Activity of Isolated Bacteriophages and Endolysin LysECD7

Spot tests were done on culture plates to visually show the bactericidal activity of the phage cocktail (Figure 6A) and recombinant endolysin (Figure 6B).

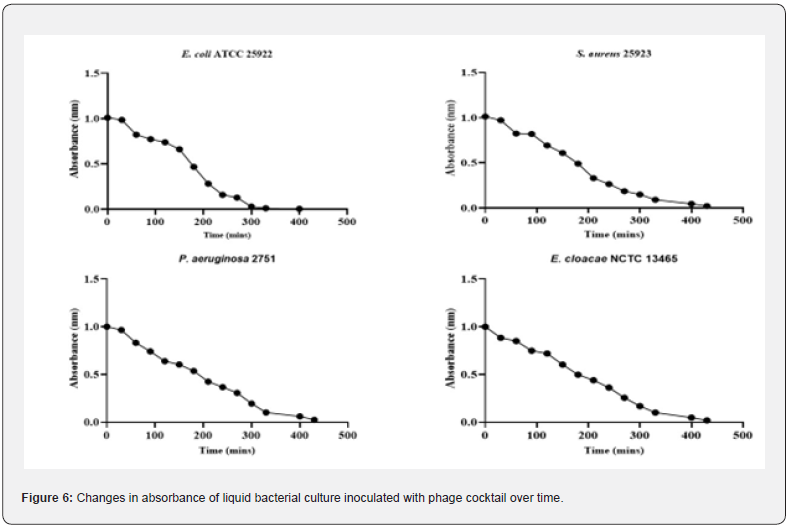

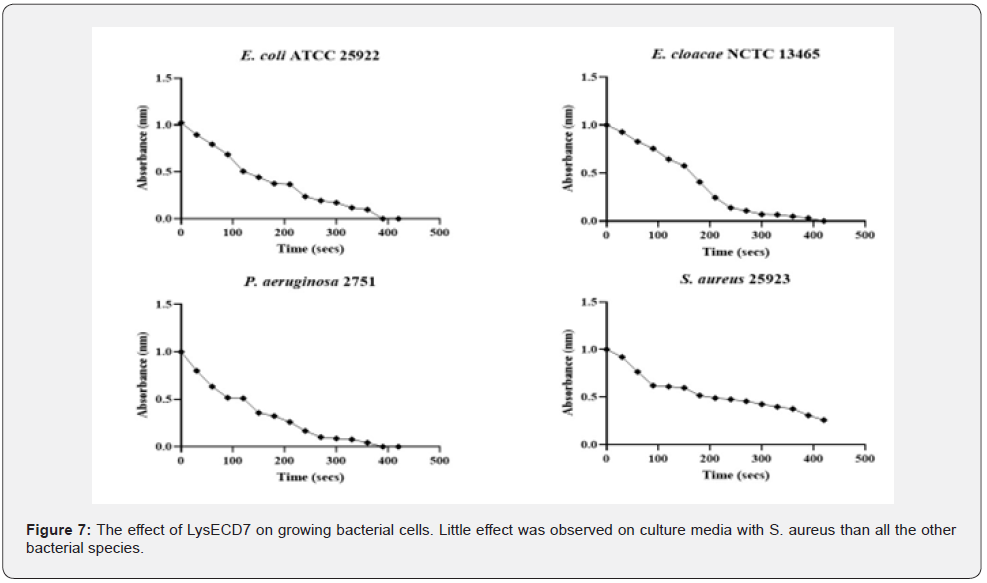

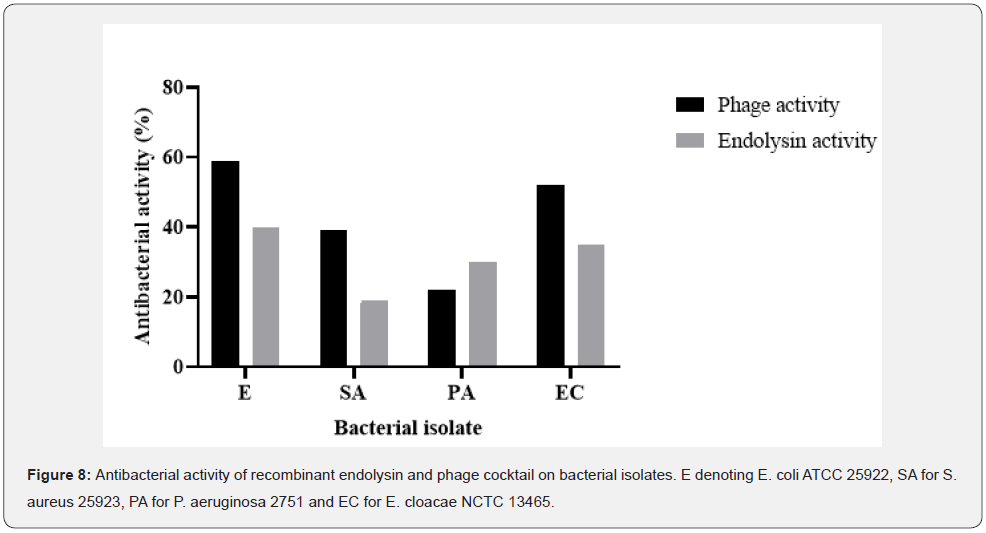

The rise in absorbance at OD600 (Figure 7) indicates that E. coli had the maximum number of bactericidal activities displayed by the phage cocktail and P. aeruginosa had the lowest activity. The endolysin demonstrated the ability to limit the growth of the clinical isolates in vitro, with varied action from the phage cocktail on the bacterial isolates. Endolysins are known to be more effective on developing cells than on cells in the stationary phase, and the effect of the produced lysin is always stronger in liquid culture, as illustrated in Figure 8 On culture plates, a spot test was carried out to demonstrate the presence of the lytic enzyme and the degree of clearance, as shown in Figure 6B. Although lysins are thought to have little effect on bacteria in the stationary phase, the zones of clearance were much greater than anticipated due to the protein’s diffusion in the media.

For this particular investigation, the recombinant endolysin (LysECD7) demonstrated lower antibacterial activity than the bacteriophage cocktail when variations in treatment efficacy were examined (p > 0.005). In comparison to the 200 μg/ml recombinant endolysin, the antibacterial activity of the bacteriophage cocktail and recombinant endolysin was revealed in Figure 8 to have greater activity and affinity to the bacterial species. With an average activity of 50.05% and 43.71%, respectively, E. coli ATCC 25922 and E. cloacae NCTC 13465 had the greatest levels of both activities.

While S. aureus 25923 had low recombinant endolysin activity (19.55% activity), the cocktail of bacteriophages had relatively high activity (39.33%), indicating a higher affinity for the cocktail than for the endolysin. P. aeruginosa 2751 had the lowest antibacterial activity in relation to E. coli ATCC 25922, having an average antibacterial activity of 26.41% for both treatments (Figure 8).

Discussion

The study’s objective was to investigate the dynamics of success while using bacteriophages and endolysin in place of conventional antibiotics. The effectiveness of environmental isolates of bacteriophages and LysECD7 on bacterial growth was examined in antimicrobial assays using clinical bacterial isolates from the ESKAPE group of pathogens as an example. Because the phages recycle and degrade their bacterial host genome for their DNA synthesis, the plaque-forming units show that they lacked integrases. As a result, they lack the molecular basis for coexistence with the host bacteria [29,30]. This characteristic also lowers the possibility of in situ DNA transformation brought on by phage lysis [31], demonstrating a very high susceptibility and effectiveness of phage induction by bacteria. The isolated phages were distinguished from one another by the resultant DNA, which was extracted and examined using molecular techniques, although they all shared a common ancestor. An effective screen was provided by the RAPDs analysis, which revealed variation among the phages. The diversity of the isolated phages was not significant, but it is sufficient to have various phages that evolved in response to competition, phages that originated from the same lineage of ancestors, and phages that evolved as a result of random naturally occurring mutations in the genetic makeup [32,33]. The development of tolerance to any therapeutic agent compromises its efficacy from the first time it is administered [34], and this is true for the majority of medicines used to treat microbial diseases. The synergy of many phages in a cocktail of quickly developing bacterial cells can be the cause of the high activity displayed by bacteriophages, but this cannot be seen in stationary phase cells. Upon induction, cells were lysed quickly, but over time, alterations to the bacterial cell wall due to mutation, CRISPR-Cas-mediated resistance, and/or adjustments to the attachment sites resulted in resistance mechanisms that slowed lysis [35-38].

The lowest bacteriophage activity was observed for Pseudomonas aeruginosa 2751 and the highest bacteriophage activity was observed for Enterobacter cloacae NCTC 13465, which in some ways demonstrates P. aeruginosa’s capacity to quickly evolve a resistance mechanism preventing infection. Endolysins were able to directly target and destroy the peptidoglycan layer of cells without entering the cells due to the effect of lysis from without [39], which reduced the threat posed by bacterial efflux pumps. Under the same circumstances, bacteriophage and endolysin activity fluctuate within bacterial isolates, demonstrating that neither substance’s activity is dependent on concentration. Endolysin action at such a low concentration demonstrates its potency and effectiveness against stationary and developing bacterial cells, making it a possible top-rank alternative therapy to antibiotics that are currently used in medicine [8,9]. The endolysin can function effectively at incredibly low quantities, as seen by the highest endolysin activity observed for Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Pseudomonas aeruginosa 2751, Enterobacter cloacae NCTC 13465, and the lowest endolysin activity observed for Staphylococcus aureus 25923. A single dose of endolysin with such potent antibiotic activity has been shown to lower mortality rates of hospital-acquired infections [40,41], opening up new therapeutic options for Gram-negative infections [42,43].

According to Antonova et al. [44], adding the amino polycarboxylic acid EDTA or changing the pH to a slightly acidic level has been observed to increase the activity of lysins, and the absence of these in the antibacterial assay may have decreased endolysin activity [1,44,45]. Smaller doses of lysins can easily reach most parts of the circulatory system since they disperse faster in media and blood than antibiotics do [46,47]. By immediately attacking the peptidoglycan layer of the bacterial cell wall, lysins can directly attack and lyse colonizing bacteria with a low likelihood of attachment site mismatch [20]. The differences between phages and host bacteria, as well as the laws governing the use and application of lysins for therapy, are the only two factors that currently limit lysin therapy [20,48,49]. However, the bacteriophage mixtures were more active than the endolysin when evaluated for effectiveness against bacterial isolates. Endolysin has the potential to be utilized as an alternative to antibiotics, as evidenced by the modest concentration that was used and the average antibacterial activity of 31.48% across all test pathogens that it produced. LysECD7 demonstrated less antibacterial activity than bacteriophage cocktails on developing cells in culture media, although lysin is known to have a higher antibacterial activity than bacteriophages on growing cells in their mid-log phase. The isolation process and other contaminants that might have contaminated the lab samples and interfered with the activity and folding of the endolytic protein may have contributed to the endolysin’s low efficacy [50-53].

Conclusion

A single dose of low endolysin concentration had a very significant antibacterial activity, bacteriophage treatment of bacterial isolates varied greatly per each species under the same conditions, and a delay in bacteriophage inoculation resulted in high bacterial CFU and low burst size (pfu/ml) of phage. These four findings from this study stand out as particularly interesting. Most nations’ rules surrounding the use of viruses as therapeutic agents in healthcare systems, together with variances in the attachment sites between the host bacterial species and the bacteriophage, are the main causes of bacteriophage therapy’s limits. The selection of combinations that successfully decrease the development of resistance in a bacterial population can be facilitated by our present understanding of phage-bacteria systems. It should be noted that each medication has a different effect on the activity and effectiveness of lysin and bacteriophage. Phage-based techniques, such as phage display and phage typing, have also evolved into standard operating procedures in molecular biology labs and have been adapted to several additional uses, such as serving as drug delivery systems when not being utilized in therapy. Under the same circumstances, bacteriophage and endolysin activity change within bacterial isolates, demonstrating that activity is independent of concentration. Lysin activity was highest in E. coli and lowest in the other bacterial species, but it should be emphasized that lysin and bacteriophage activity and efficacy differ with each treatment.

Author Contribution

TAC and ISN oversaw the study’s conceptualization, project design, initial draft writing, and manuscript editing. ISN edited the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the technical support from Mr. Hillary Zharo and members of the Molecular Biology Teaching Laboratory.

References

- Antonova N, Vasina D, Lendel A, Usachev E, Makarov V, et al.(2019) Broad Bactericidal Activity of the Myoviridae Bacteriophage Lysins LysAm24, LysECD7, and LysSi3 against Gram-Negative ESKAPE Pathogens. Viruses 11: 284.

- Moons P, Faster D, Aertsen A (2013) Lysogenic conversion and phage resistance development in phage exposed Escherichia coli biofilms. Viruses 5:150–61.

- Edgar R, Friedman N, Molshanski MorS , Qimron U (2012) Reversing bacterial resistance to antibiotics by phage-mediated delivery of dominant sensitive genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 744–51.

- Kovalskaya NY, Herndon EE, Foster Frey JA, Donovan DM, Hammond RW (2019) Antimicrobial activity of bacteriophage derived triple fusion protein against Staphylococcus aureus. AIMS Microbiol 5: 158.

- Alves Dr, A Gaudion A, Bean JE, Perez Esteban, Tc PArnot, et al. (2014) Combined Use of Bacteriophage K and a Novel Bacteriophage To Reduce Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation. Appl Environ Microbiol 80: 6694–6703.

- Lehman SM, Mearns G, Rankin D, Cole RA, Smrekar F, et al. (2019) Design and preclinical development of a phage product for the treatment of antibiotic-resistant staphylococcus aureus infections. Viruses 11.

- Weitz JS, Dushoff J (2008) Alternative stable states in host–phage dynamics. Theor Ecol 1: 13-19.

- Fischetti VA (2018) Development of phage lysins as novel therapeutics: A historical perspective. Viruses 10.

- Fischetti VA (2017) Lysin Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus and Other Bacterial Pathogens. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 409: 529–540.

- Brüssow H (2014) Editorial Commentary: Phage therapy: Quo Vadis? Clin Infect Dis 58: 535–536.

- Brüssow H, Canchaya C, Hardt WD (2004) Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68: 560–602.

- Brüssow H, Hendrix R W (2002) Phage Genomics: Small Is Beautiful. Cell 108: 13-16.

- Schmelcher M, Powell AM, Becker SC, Camp MJ, Donovan DM (2012) Chimeric phage lysins act synergistically with lysostaphin to kill mastitis-causing Staphylococcus aureus in murine mammary glands. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 2297–2305.

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, Russell DA, Ford K, et al. (2019) Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Med 25: 730–733.

- Hatfull G, Hendrix RW (2011) Bacteriophages and their genomes. Curr Opin Virol 1: 298–303.

- Tang SS, Biswas SK, Tan WS, Saha AK, Leo BF (2019) Efficacy and potential of phage therapy against multidrug resistant Shigella spp. PeerJ 7: e6225.

- Chan CA, Stanley G, Modak M, Koff JL, Turner PE (2021) Bacteriophage therapy for infections in CF. Pediatr Pulmonol 56: S4–S9.

- Enault P, Briet A, Bouteille L, Roux S, Sullivan MB, et al. (2017) Phages rarely encode antibiotic resistance genes: a cautionary tale for virome analyses. ISME J 11: 237-247.

- Happel AU, Balle C, Maust BS, Konstantinus IN, Gill K, et al. (2021) Presence and Persistence of Putative Lytic and Temperate Bacteriophages in Vaginal Metagenomes from South African Adolescents. Viruses 13: 2341.

- Abedon ST (2011) Lysis from without. Bacteriophage 1: 46–49.

- Connerton PL, Timms AR, Connerton IF (2011) Campylobacter bacteriophages and bacteriophage therapy. J Appl Microbiol.

- Iwano H, Inoue Y, TakasagoT , Kobayashi H, Furusawa T et al. (2018) Bacteriophage ΦSA012 Has a Broad Host Range against Staphylococcus aureus and Effective Lytic Capacity in a Mouse Mastitis Model. Biology (Basel) 7: 8.

- Malik DJ, Sokolov IJ, Vinner GK, Mancuso F, Cinquerrui S et al. (2017) Formulation, stabilisation and encapsulation of bacteriophage for phage therapy. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 249: 100–133.

- Kaur G, Agarwal R, Sharma RK (2021) Bacteriophage Therapy for Critical and High-Priority Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Phage Cocktail-Antibiotic Formulation Perspective. Food Environ Virol 2021 134(13): 433–446.

- Weinbauer MG (2004) Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol.

- Yang H, Yu J, Wei H (2014) Engineered bacteriophage lysins as novel anti-infectives. Front. Microbiol. 5, 542.

- Briers Y, Walmagh M, Van Puyenbroeck V, Cornelissen A, Cenens, et al. (2014) Engineered endolysin-based “Artilysins” to combat multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens. MBio 5.

- Sambrook J, Fritsch E, ManiatisT (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed., Vols. 1,2,3Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA.

- Bobay LM, Rocha EPC, Touchon M (2013) The adaptation of temperate bacteriophages to their host genomes. Mol Biol Evol 30: 737-51.

- Colavecchio A, Souza YD, Tompkins E, Jeukens J, Freschi L, et al. (2017) Prophage Integrase Typing Is a Useful Indicator of Genomic Diversity in Salmonella enterica. Front Microbiol 8: 1283.

- Ghosh P, Wasil LW, Hatful GF (2006) Control of Phage Bxb1 Excision by a Novel Recombination Directionality Factor. PLoS Biol 4: e186.

- Corbel MJ (1997) Brucellosis: An Overview. Emerg Infect Dis 3: 213–221.

- Xia G, Wolz C (2014) Phages of Staphylococcus aureus and their impact on host evolution. Infect Genet Evol.

- Walsh TR (2006) Combinatorial genetic evolution of multiresistance. Curr Opin Microbiol 9: 476–482.

- Bull JJ, Levin BR, DeRouin T, Walker N, Bloch CA (2002) Dynamics of success and failure in phage and antibiotic therapy in experimental infections. BMC Microbiol 2: 35.

- Khan Mirzaei M, Nilsson AS (2015) Isolation of Phages for Phage Therapy: A Comparison of Spot Tests and Efficiency of Plating Analyses for Determination of Host Range and Efficacy. PLoS One 10: e0118557.

- Maciejewska B, Olszak T, Drulis Kawa Z (2018) Applications of bacteriophages versus phage enzymes to combat and cure bacterial infections: an ambitious and also a realistic application? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102: 2563–2581.

- McDonnell B, Mahony J, Hanemaaijer L, Kouwen TRHM, van Sinderen D (2018) Generation of bacteriophage-insensitive mutants of Streptococcus thermophilus via an antisense RNA CRISPR-Cas silencing approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 84.

- Abedon Sk, Kuhl SJ, Blasdel BG, Kutter EM (2011) Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage 1: 66-85.

- Gutiérrez D, Fernández L, Rodríguez A, García P (2018) Are phage lytic proteins the secret weapon to kill staphylococcus aureus?

- Vázquez R, García E, García P(2018) Phage Lysins for Fighting Bacterial Respiratory Infections: A New Generation of Antimicrobials. Front Immunol 9: 2252.

- Ghose C, Euler CW (2020) Gram-Negative Bacterial Lysins. Antibiotics 9: 74.

- Kovalskaya N, Foster Frey J, Donovan DM, Bauchan G, Hammond RW, et al. (2016) Antimicrobial Activity of Bacteriophage Endolysin Produced in Nicotiana benthamiana Plants. J Microbiol Biotechnol 26: 160–170.

- Antonova N, Vasina D, Rubalsky E, Fursov M, Savinova A, et al. (2020) Modulation of Endolysin LysECD7 Bactericidal Activity by Different Peptide Tag Fusion. Biomolecules 10: 440.

- Oliveira H, Boas DV, Mesnage S, Kluskens LD, Lavigne R, et al. (2016) Structural and enzymatic characterization of ABgp46, a novel phage endolysin with broad anti-gram-negative bacterial activity. Front Microbiol p. 7.

- Maciejewska B, Zrubek K, Espaillat A, Wisniewska M, Rembacz KP, et al. (2017) Modular endolysin of Burkholderia AP3 phage has the largest lysozyme-like catalytic subunit discovered to date and no catalytic aspartate residue. Sci Rep 7: 14501.

- Pastagia M, Schuch R, Fischetti VA, Huang DB (2013) Lysins: The arrival of pathogen-directed anti-infectives. J Med Microbiol 62(pt10): 1506–1516.

- Domingo Calap P, Delgado Martínez J (2018) Bacteriophages: Protagonists of a Post-Antibiotic Era. Antibiotics 7: 66.

- Storms ZJ, Sauvageau D (2015) Modeling tailed bacteriophage adsorption: Insight into mechanisms. Virology.

- Hatfull G, Hendrix RW (2011) Bacteriophages and their genomes. Curr Opin Virol 1: 298–303.

- Adams MH (1959) Methods of study of bacterial viruses. Bacteriophages.

- Brüssow H, Canchaya C, Hardt WD (2004) Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 68: 560–602.

- Chan CA, Stanley G, Modak M, Koff JL, Turner PE, et al. (2021) Bacteriophage therapy for infections in CF. Pediatr Pulmonol 56: S4–S9.