Psychometric Properties of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and Prevalence of Alcohol use Among SA Site-based Construction Workers

Paul Bowen1* and Rita Peihua Zhang2

1Department of Construction Economics and Management, University of Cape Town, South Africa

2School of Property, Construction & Project Management, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

Submission: September 21, 2021; Published: October 04, 2021

*Corresponding Author: Paul Bowen, Department of Construction Economics and Management, University of Cape Town, South Africa

How to cite this article: Paul Bowen, Rita Peihua Zhang. Psychometric Properties of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and Prevalence of Alcohol use Among SA Site-based Construction Workers. Civil Eng Res J. 2021; 12(3): 555837 DOI 10.19080/CERJ.2021.12.555837

Abstract

Construction workers in SA are regarded a high-risk group in the context of HIV/AIDS. Excessive alcohol use is associated with risky lifestyles and lack of condom use, decreased uptake of HIV testing, and poor adherence to ARV treatment. Excessive alcohol consumption is also associated with depression and illicit drug use. Screening is widely employed in the detection of problematic alcohol consumption; the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) being extensively used for this purpose. This study examines both the psychometric properties of the AUDIT (one-, two-, and three-factor models) and the prevalence of alcohol use among construction workers. A field-administered survey was used to gather data from 496 male workers drawn from 18 construction sites of 7 construction firms. Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and confirmatory factor analyses were used to analyze the prevalence of alcohol use, as well as the dimensionality, reliability, and construct validity of the AUDIT. Nearly 50% of participants reported never consuming alcohol. Including abstainers, three quarters of participants were classed as low risk (score <8). The at-risk workers were categorized as follows: 17.3% at medium risk (score 8-15); 3.6% at high risk (score 16-19); and 3.8% at very high risk (score 20+). Notably, of the 250 workers who reported using alcohol, 14.8% may be categorized as being at high-to-very high risk. In essence, 24.8% of construction participants were classed as engaging in hazardous or harmful drinking. Internal consistency of the AUDIT was very good. A 1-factor measurement model was indicated, the output indices presenting satisfactory model fit to the data. All factor loadings were significant. Concurrent validity was demonstrated. Further work is indicated in relation to items 9 and 10 of the AUDIT, as these particular items do not perform as well as the remaining items. The contribution of these two items needs to be examined using item response theory (IRT).

Keywords: Hazardous alcohol consumption; The AUDIT; Construction workers; South Africa

Introduction

Construction workers in South Africa are regarded as a high-risk group in the context of HIV/AIDS [1]. Use of alcohol, the most commonly used substance in South Africa [2], contributes to the rapid spread of HIV [3]. Excessive use of alcohol has been found to be associated with risky lifestyles and lack of condom use [4], decreased uptake of HIV testing [5], and poor adherence to ARV treatment [6]. Excessive alcohol consumption is also associated with depression [7] and illicit drug use [8]. Screening is a widely used method for the detection of problematic alcohol consumption [9]. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [10] is extensively used for this purpose [11]. The AUDIT consists of 10 items, covering three domains of at-risk alcohol use, namely, hazardous alcohol use (items 1-3), dependence symptoms (items 4-6), and harmful alcohol use (items 7-10). The AUDIT responses are each denoted a score in the AUDIT table (e.g., ‘Never’ = 0, ‘less than monthly’ = 1, ‘2-4 times a month’ = 2, and so on). The total AUDIT score is determined by adding the score of all of the responses. The maximum score is 40. Total AUDIT scores lower than 8 indicate low-risk alcohol use. Scores in the range 8-15 indicate medium risk and a hazardous drinking pattern, those in the range 16-19 indicate high-risk and a harmful drinking pattern, whilst those 20+ are indicative of very high risk and a dependent drinking pattern. An assessment of hazardous or harmful drinking is made if the score is 8 or more [12]. Although the AUDIT was initially developed as a one-dimensional measure, evidence relating to the factorial structure is equivocal. Whilst the one-dimensional factorial structure has been supported by some studies [13,14,15], numerous other studies have favored a multi-dimensional factorial structure [16,17]. For example, Bergman & Källmén [18], employing CFA to compare one-, two-, and three-factor solutions for a Swedish general population, reported the superiority of multiple factor models over a single-factor model. Tetrick [19] and Depaoli et al. [20] emphasize the pivotal role the measurement of occupational health psychology constructs plays in improving our understanding of occupational health and well-being, and its importance in the design, evaluation, and implementation of interventions in improving employees’ and organizations’ well-being. Given the behavioral associations between the use and abuse of alcohol, risky sexual behaviour, and HIV/AIDS, it is considered necessary to examine both the psychometric properties of the AUDIT as well as estimate the prevalence of alcohol use among construction workers. This is important in terms of targeted management interventions employers can offer.

Methods

Participants and setting

Data were collected from site-based construction employees (n=556), comprising unskilled and skilled workers, and site office-based staff. Participants were drawn from 18 construction sites in the Western Cape, involving 7 construction firms. Of these, 496 were deemed suitable for analysis. The AUDIT data were determined to be positively skewed (non-normally distributed). The demographic characteristics of participants are given below.

Measures

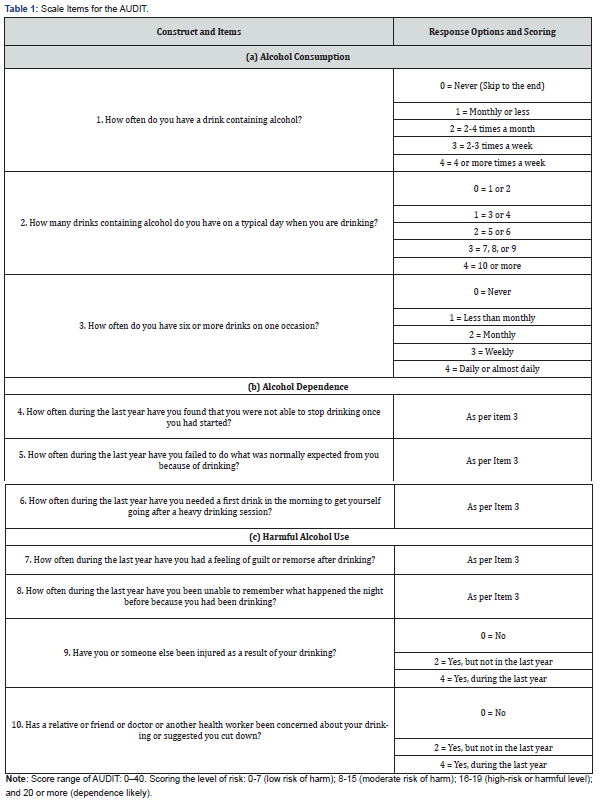

Items comprising the AUDIT, their response options, and associated scoring regimen are depicted in (Table 1). Concurrent validity of the AUDIT was assessed using the 1 factor, 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D-10) Scale [21,22] (= .89) and the 1 factor, 11-item Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) [23,24] (= .93).

Analysis

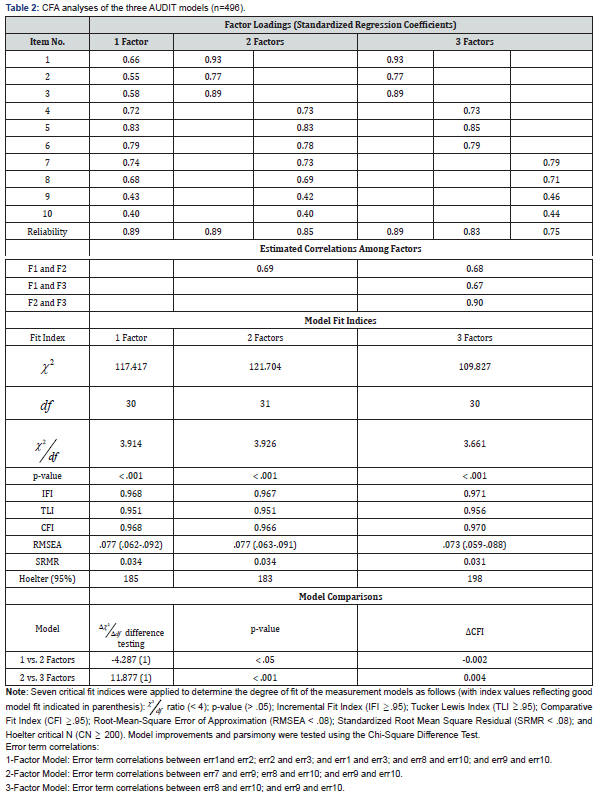

Descriptive, bivariate, and multivariate analyses were performed. Unweighted scale scores were created by summating the scores of the 10 constituent AUDIT items. Internal consistency (reliability) was determined using Cronbach’s alpha and correlation analysis was performed to assess the magnitude, direction, and significance of associations between the factors of interest. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) using AMOS ver. 27 were undertaken to verify the factorial structure of the AUDIT, using the model fit indices shown in (Table 2). It is suggested that the factorial structure of the AUDIT may vary depending on the population of the study [25]. For this reason, the one-, two-, and three-factor models of the AUDIT were tested. Finally, concurrent validity was assessed. The 3-factor model reflects the three conceptual domains of at-risk alcohol use as noted above (items 1-3; 4-6; 7-10). The 2-factor model reflects one factor comprising the consumption items (items 1-3), and a second factor consisting of items reflecting alcohol-related consequences (items 4-10). The 1-factor model comprised the full set of 10 items, aligning with the notion of a total AUDIT score. Correlations among factors were assessed for the two- and three-factor models.

Results

Worker characteristics

Participants were male, ‘Black’ African (59.3%), with ages ranging from 18 - 67 years (M= 35.6; SD=10.1) with a median of 34 years. Most workers were married or living with a partner (48.2%), followed by single persons (43.9%). The remainder were widowed, separated, or divorced. A majority (59.7%) did not possess a matric (school leaving qualification), with less than a quarter (24.1%) claiming to have completed matric. General workers (labourers) were the predominant occupational group (50.4%), followed by skilled workers (14.5%). Supervisory staff accounted for 10.7%. The majority of workers were employed on either a permanent monthly contract (24.8%), a fixed term monthly contract (23.8%), a permanent hourly contract (22.3%), or a fixed term hourly contract (16%). In this context, ‘permanent’ refers to the core, retained workforce of the firm, whereas hourly contracts refer to casual workers.

Assessment of the one-, two-, and three-factor models of the AUDIT

The results of the CFA analyses are depicted in (Table 2). The one-factor model indicated satisfactory

fit to the data,  = 3.914, CFI = 0.968, RMSEA = 0.077, Hoelter = 185,

and reliability of α = 0.89. Error term correlations were permitted as indicated in (Table 2) due to overlaps in these items. This is not problematic as they are conceptualized as part of the same factor

(or sub-factors) as the case may be. Item loadings were satisfactory to good, except for items 9 and 10 (< .50). The fit of the two-factor model

was very similar to that of the one-factor model, with

= 3.914, CFI = 0.968, RMSEA = 0.077, Hoelter = 185,

and reliability of α = 0.89. Error term correlations were permitted as indicated in (Table 2) due to overlaps in these items. This is not problematic as they are conceptualized as part of the same factor

(or sub-factors) as the case may be. Item loadings were satisfactory to good, except for items 9 and 10 (< .50). The fit of the two-factor model

was very similar to that of the one-factor model, with  = 3.926, CFI = 0.966,

RMSEA = 0.077, and Hoelter (95%) = 183 and reliability of α = 0.89 for the drinking habits factor and α = 0.85 for the consequences factor. The estimated

correlation between the two factors was strong (0.69). Item loadings were good, again with the exception of items 9 and 10 (< .50). The Chi-square

change between the two-factor model and the one-factor model was negative, suggesting a deterioration instead of an improvement, lending support to a

one-factor model.

= 3.926, CFI = 0.966,

RMSEA = 0.077, and Hoelter (95%) = 183 and reliability of α = 0.89 for the drinking habits factor and α = 0.85 for the consequences factor. The estimated

correlation between the two factors was strong (0.69). Item loadings were good, again with the exception of items 9 and 10 (< .50). The Chi-square

change between the two-factor model and the one-factor model was negative, suggesting a deterioration instead of an improvement, lending support to a

one-factor model.

The fit of the three-factor model was very similar to both previous models,

with  = 3.661, CFI = 0.970, RMSEA = 0.073,

and an improved Hoelter (95%) = 198. However, in contrast to the good reliability reflected in the previous two models,

the three-factor model indicated= .89 for the drinking habits factor, = .83 for the dependencies factor, and a comparatively

low= .75 for the harmful alcohol use factor. The estimated correlations between the three factors were all strong: 0.67 between

factors 1 and 2; and 0.90 between factors 2 and 3. This latter correlation is very high, suggesting that the second and third factors

show poor discriminant validity and should be grouped together [26], thus disapproving a three-factor structure. Item loadings were good,

again with the exception of items 9 and 10 (< .50). The Chi-square Difference Test indicated that the three-factor model was a significant

improvement upon the two-factor model, albeit very modest.

= 3.661, CFI = 0.970, RMSEA = 0.073,

and an improved Hoelter (95%) = 198. However, in contrast to the good reliability reflected in the previous two models,

the three-factor model indicated= .89 for the drinking habits factor, = .83 for the dependencies factor, and a comparatively

low= .75 for the harmful alcohol use factor. The estimated correlations between the three factors were all strong: 0.67 between

factors 1 and 2; and 0.90 between factors 2 and 3. This latter correlation is very high, suggesting that the second and third factors

show poor discriminant validity and should be grouped together [26], thus disapproving a three-factor structure. Item loadings were good,

again with the exception of items 9 and 10 (< .50). The Chi-square Difference Test indicated that the three-factor model was a significant

improvement upon the two-factor model, albeit very modest.

Both the similarity of the fit indices of the three models, and the chi-square change statistics, indicate supporting a one-factor structure for the AUDIT, thus aligning with a number of previous studies [13,14,15]. In contrast, our results findings do not align with studies favouring a two-factor [27,25,28] or three-factor [29,30] AUDIT framework, respectively. This finding has practical implications. As the total sum of the AUDIT is typically used as a cut-off score to indicate potentially excessive alcohol use [12], this is only appropriate if the AUDIT can be considered one-dimensional. Given the present results favouring a one-factor AUDIT structure, a sum score can continue to be considered as an appropriate indicator of problematic drinking. This decision aligns with the literature, where it is shown that samples with a low prevalence of alcohol dependence report multiple-factor structures for the AUDIT, compared to samples with a high prevalence of alcohol dependence where the AUDIT showed a single factor structure (see Moehring et al. [28] This is relevant as it will be shown below that the alcohol consumption of male construction workers is higher than that of males in the general population [31]. Having established a satisfactory factorial structure for the AUDIT, the concurrent validity of the AUDIT was examined. The AUDIT was shown to be positively associated with both drug use (DUDIT) (r=.30, p<.001) and depression (CESD-D-10) (r=.15, p<.001), indicative of concurrent validity. The magnitude of AUDIT’s association with DUDIT was medium and with depression (CESD-D-10) it was small. Having explored the psychometric properties of the AUDIT, it was then used to estimate the prevalence of hazardous or harmful drinking among construction workers in Cape Town.

Alcohol consumption

Nearly 50% (n=246) of participants reported that they never consume alcohol. Including these abstainers, a total of 373 (75.2%) participants were classed as low risk (score <8). The at-risk workers were categorized as follows: 17.3% (n=86) at medium risk (score 8-15); 3.6% (n=18) at high risk (score 16-19); and 3.8% (n=19) at very high risk (score 20+). However, of the 250 workers who reported using alcohol, 37 (14.8%) may be categorized as being at high-to-very high risk. In essence, 24.8% (n=123) of construction participants are classed as engaging in hazardous or harmful drinking. This information provides pointers for targeted interventions by employers.

Discussion

A one-factor structure of the AUDIT is supported in this study, which aligns with the results from studies using samples with a high prevalence of alcohol dependence [14]. Indeed, construction workers have been consistently identified as an occupation group with elevated risks of alcohol use problems [32,33]. In this study, current alcohol use was reported by 50.4% of male construction workers, markedly higher than the 41.5% prevalence estimate reported by Peltzer et al. [31] in respect of males in the general South African population. Peltzer et al. [31] also noted that hazardous or harmful drinking was reported by 17% of men, whereas in the current study it was reported by nearly a quarter of male construction workers (24.8%). This does not bode well for the health of such workers classified as hazardous or harmful drinkers, nor for their employer organizations. Alcohol consumption problems can cause short-term absenteeism (e.g., due to ‘hangovers’) and long-term absenteeism (e.g., due to alcohol- related injuries and accidents, as well as incapacitation), which lead to substantial productivity loss and financial costs [34]. This is cause for concern and calls for effective targeted interventions by construction employers.

The identification of a one-dimensional structure of AUDIT in this study supports the conventional adoption of AUDIT as a screening instrument for detecting at-risk alcohol drinking [12]. Construction employers can therefore use the AUDIT to screen for hazardous or harmful drinking among construction workers for intervention purposes. Traditionally, workplace alcohol screening and interventions focus on individuals. Employers use alcohol screening to identify workers with problematic alcohol consumption for behavioral control and change, for example, through sanctions or education programs [35]. However, research evidence shows that risky alcohol consumption by construction workers is associated with not only individual characteristics (e.g., low education, norms and attitudes toward alcohol, social-economic status) but also a variety of organizational factors such as workplace psychosocial environment (e.g., abusive supervisory leadership, high workload, high work stress, low social support, low work control), employment quality (e.g., job insecurity, shift work), and normative influences (e.g., workplace drinking norms, use alcohol to unwind after work) [36]. It is recommended that alcohol intervention strategies should be multifaceted and supplementary, changing individual alcohol-related beliefs and behaviours as well as addressing factors relating to workplace culture and work conditions [37].

Despite the AUDIT exhibiting good psychometric properties regarding internal reliability, factorial structure, and concurrent validity in this study, items 9 and 10 of the scale do not perform as well as the remaining items in terms of factor loadings. A similar phenomenon was also detected by Doyle et al. [25], where low factor loadings were reported for items 9 and 10 in different factorial structures across different samples. This phenomenon can possibly be explained by two reasons. First, the consequences depicted in items 9 (i.e., drinking-related injury) and 10 (i.e., others’ concerns about drinking) are extremely severe and thus are low probability events. Second, while all other items assess participants’ own experiences, items 9 and 10 assess the experiences and reactions of other people. The way that the two items were constructed may have led participants to respond to these two items differently compared to the other eight items. It is recommended that the performances of these two items be further examined using the assessment technique of item response theory (IRT), which assesses item properties within and across individuals.

Conclusion

The AUDIT demonstrates promise as a valid, reliable, one-factor scale to measure hazardous or harmful drinking by construction workers. The elevated level of current alcohol consumption by male construction workers, coupled with the greater degree to which workers in the industry engage in hazardous or harmful drinking compared to males in the general population, is cause for concern. Multifaceted interventions by construction organizations are required to change alcohol-related beliefs and behaviours of high-risk drinkers and to create a working environment with a positive workplace culture, good work conditions, and a high awareness of the problems associated with harmful or hazardous drinking. Future studies would usefully be directed at assessing the impact of problem drinking in the construction industry, possibly in terms of health and safety issues, productivity, and social concerns, amongst others.

References

- Bowen PA, Dorrington R, Distiller G, Lake H, Besesar S (2008) HIV/AIDS in the South African construction industry: an empirical study. Construction Management and Economics 26(8): 827-839.

- Shisana O, Stoker D, Simbayi LC, Orkin O, Bezuidenhout F, et al. (2004) South African National Household Survey of HIV/AIDS Prevalence, Behavioural Risks and Mass Media Impact: detailed methodology and response rate results. South African Medical Journal 94(4): 283-288.

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Cain D, Jooste S, (2007) HIV/AIDS risk reduction counseling for alcohol using sexually transmitted infections clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 44(5): 594-600.

- Parry CDH, Plüddemann A, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, et al. (2005) Alcohol use in South Africa: Findings from the first demographic and health survey (1998). Journal of Studies on Alcohol 66(1): 91-97.

- Jooste S, Mabaso M, North A, Shean Y, Simbayi LC (2020) Socio-economic Status and Associated Factors in the Uptake of HIV Testing: Findings from the South African Population-based National Household Survey Conducted in 2017. BMC Public Health.

- Kader R, Govender R, Seedat S, Koch JR, Parry C (2015) Understanding the Impact of Hazardous and Harmful Use of Alcohol and/or Other Drugs on ARV Adherence and Disease Progression. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0125088.

- Kuria MW, Ndetei DM, Obot IS, Khasakhala LI, Bagaka BM, et al. (2012) The Association between Alcohol Dependence and Depression before and after Treatment for Alcohol Dependence. International Scholarly Research Notices.

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kagee A, Toefy Y, Cain D, et al. (2006) Association of poverty, substance use, and HIV transmission risk behaviors in three South African communities. Social Science and Medicine 62(7): 1641-1649.

- Wolford GL, Rosenberg SD, Drake RE, Mueser KT, Oxman TE et al. (1999) Evaluation of methods for detecting substance use disorder in persons with severe mental illness. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 13(4): 313-326.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M (1993) Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT: WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption-II. Addiction 88(6): 791-804.

- Berner MM, Kriston L, Bentele M, Härter M (2007) The alcohol use disorders identification test for detecting at-risk drinking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 68(3): 461-473.

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG (2001) AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care. Second edition World Health Organization Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence.

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Chandra PS (2003) Psychometric evaluation of the alcohol use disorders identification test and short drug abuse screening test with psychiatric patients in India. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64(7): 767-774.

- Skipsey K, Burleson JA, Kranzler HR (1997) Utility of the AUDIT for identification of hazardous or harmful drinking in drug-dependent patients. Drug and alcohol dependence 45(3): 157-163.

- Skogen SC, Thørrisen MM, Olsen E, Hesse M, Aas RW (2019) Evidence for essential unidimensionality of AUDIT and measurement invariance across gender, age and education. Results from the WIRUS study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 202: 87-92.

- Lima CT, Freire AC, Silva AP, Teixeira RM, Farrell M, et al. (2005) Concurrent and construct validity of the audit in an urban Brazilian sample. Alcohol and Alcoholism 40(6): 584-589.

- von der Pahlen B, Santtila P, Witting K, Varjonen M, Jern P, Johansson A, et al. (2008) Factor structure of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) for men and women in different age groups. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 69(4): 616-621.

- Bergman H, Källmén H (2002) Alcohol use among Swedes and a psychometric evaluation of the alcohol use disorders identification test. Alcohol Alcohol 37(3): 245-251.

- Tetrick LE, (2017) Trends in measurement models and methods in understanding occupational health psychology. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 22(3): 337-340.

- Depaoli S, Tiemensma J, Felt JM, (2018) Assessment of health surveys: Fitting a multidimensional graded response model. Supplement, Psychology, Health and Medicine 23(S1): 1299-1317.

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL (1994) Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 10(2): 77-84.

- Baron EC, Davies T, Lund C (2017) Validation of the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) in Zulu, Xhosa and Afrikaans populations in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry 17(6).

- Berman AH, Palmstierna T, Källmén H, Bergman H (2007) The self-report Drug Use Disorders Identification Test-Extended (DUDIT-E): Reliability, validity, and motivational index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 32(4): 357-369.

- Hildebrand M (2015) The Psychometric Properties of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT): A Review of Recent Research. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 53: 52-59.

- Doyle SR, Donovan DM, Kivlahan DR (2007) The factor structure of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 68(3): 474-479.

- Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th), Guilford publications, New York, USA.

- Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Monti PM (2002) Alcohol use disorders identification test: Factor structure in an adolescent emergency department sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 26(2): 223-231.

- Moehring A, Krause K, Guertler D, Bischof G, Hapke U, et al. (2018) Measurement invariance of the alcohol use disorders identification test: Establishing its factor structure in different settings and across gender. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 189: 55-61.

- Blair AH, Pearce ME, Katamba A, Malamba SS, Muyinda H, et al. (2017) The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Exploring the Factor Structure and Cutoff Thresholds in a Representative Post-Conflict Population in Northern Uganda. Alcohol and Alcoholism 52(3): 318-327.

- Morojele NK, Kekwaletswe CT, Nkosi S, Kitleli NB, Manda SO (2015) Reliability and factor structure of the AUDIT among male and female bar patrons in a rural area of South Africa. African Journal of Drug & Alcohol Studies 14(1): 23-35.

- Peltzer K, Davids A, Njuho P (2011) Alcohol use and problem drinking in South Africa: findings from a national population-based survey. African Journal of Psychiatry 14(1): 30-37.

- Cheng WJ, Cheng Y, Huang MC, Chen CJ (2012) Alcohol dependence, consumption of alcoholic energy drinks and associated work characteristics in the Taiwan working population. Alcohol and Alcoholism 47(4): 372-379.

- Mandell W, Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Garrison R (1992) Alcoholism and occupations: a review and analysis of 104 occupations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 16(4): 734-746.

- Pidd KJ, Berry JG, Roche AM, Harrison JE (2006) Estimating the cost of alcohol‐related absenteeism in the Australian workforce: the importance of consumption patterns. Medical Journal of Australia 185(11-12): 637-641.

- Pidd K, Roche AM (2014) How effective is drug testing as a workplace safety strategy? A systematic review of the evidence. Accident Analysis & Prevention 71: 154-165

- Roche AM, Lee NK, Battams S, Fischer JA, Cameron J, et al. (2015) Alcohol use among workers in male-dominated industries: A systematic review of risk factors. Safety science 78: 124-141.

- Cercarelli R, Allsop S, Evans M, Velander F (2012) Reducing Alcohol-related Harm in the Workplace (An Evidence Review: Full Report). Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, Melbourne, Australia.