Safety as Project Success Factor in a Civil Project: A Case Study

Hans Bakker1*, Marcel Hertogh1 and Ton Vrijdag2

1Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands

2Project Director N62 at Province of Zeeland, Netherlands

Submission: July 19, 2017; Published: September 22, 2017

*Corresponding author: Hans Bakker, Delft University of Technology, Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences, Stevinweg 1, 2628 CN Delft, Netherlands, Email: H.L.M.Bakker@TUDelft.nl

How to cite this article: H Bakker, M Hertogh, T Vrijdag. Safety as Project Success Factor in a Civil Project: A Case Study. Civil Eng Res J. 2017; 2(3): 555587. DOI: 10.19080/CERJ.2017.02.555587

Abstract

The civil industry is clearly lagging behind in safety performance compared to the chemical and process industry and more specifically to the oil & gas industry. Already for years the oil and gas industry is advocating a zero incident policy and they are making visible progress towards an incident free working environment for own staff as well as contractor staff. In many situations a project will be considered failed in that industry if an incident with lost time occurred. This is in sharp contrast with the civil industry where even last month you could hear people say that zero incidents is impossible to attain. With the present case study it will be shown that with simple measures and a real attention to staff and their well-being this goal zero is attainable and actually creating the boundary conditions for overall project success.

Keywords: Safety; Civil construction; Infrastructure; Project management; Contracting; Bowtie

Highlights

a. Civil construction projects can have a good safety record like the process industry

b. A goal of zero incidents is attainable in the civil industry

c. Real attention to people on a project and the working conditions makes a difference

d. The safety approach has to be fit for purpose, adapted to the specific industry

Introduction

For people who work or have worked in the chemical and process industry personal safety as well as process safety has become a second nature. This has taken many years and a lot of attention, but safety statistics of this industry clearly show that major steps forward have been made although not all companies have an impeccable record yet. However, over the last 20 to 30 years the improvements have been impressive. Incidents unfortunately still do happen, but are getting scarcer luckily, and these incidents do have a huge impact not only on the life and the personal circumstances of the victim(s) but also on the personal norms, values and beliefs of both managers and staff. Once you have lived through an incident with severe consequences such as permanent disability (or worse fatalities) of your staff, people always pledge “once, but never again”.

Unfortunately for some of them that insight might have come too late. People who are educated and trained in this way almost always change their behaviours with respect to safety and apply their learning in every situation, being at home, on a journey or when taking up work in a different industry. They do act as safety champions and are trying to make a difference in that new industry. The firm belief in the process industry is that when you are able to control safety, you are also controlling quality, time, budget and the like. After all with a clear focus on safety, you start thinking in risks, their consequences and the mitigating actions. And these apply equally well to the other areas that you are supposed to control or monitor. When people complain that all these safety measures are driving the costs up, the reply should simply be that the measures are far cheaper than dealing with the consequences of an incident, an accident or a fatality. On top of that, most of the measures are actually already legal requirements in most countries. Complying with the laws on labour legislation will be the first step towards an improved safety performance, but more still has to be done.

In the present study a project executed in the civil construction industry has been evaluated in more detail. The civil industry has traditionally been lagging behind in their adherence to safety legislation and compliance with the safety rules. There is still a bit of a macho culture, doing things based on years of experience where taking precautions, the lowest level of safety awareness, is already seen as a weakness. Within the project under study it has been shown that the performance on the subject of safety can drastically be improved and consequentially the performance of the project overall is at the same time much better than other projects in the civil industry. The study will not only be focussing on safety but also on the overall management of the project, since the authors strongly believe that the two are closely interconnected.

The present case study is based on the experience of the project team, gathered via interviews and observations, and has been evaluated based on interviews with staff, interviews with management of all the participating companies and by discussions with experts in the field of project management, safety and contract management. In the second paragraph a brief overview ofthe development of the safety approach in the process industry and the civil industry will be highlighted. In the third paragraph the approach followed in managing this particular project will be detailed after which in the fourth paragraph the specific approach for improved safety is explained. In the fifth paragraph the experiences of the management teams of the participating companies will be evaluated via interviews. The study and the learning will be concluded in the final paragraph.

Literature

The literature on safety is abundant. It is not the intent to summarise it all here, but a few of the important elements used in the present project will be highlighted. As will be shown later, staff coming from the process industry has triggered the present approach. Starting from the present thinking in the process industry, the switch will be made to the civil industry. In order to set the scene a quick scan has been done on the reported safety statistics in the two industries that we have been talking about up to now. The oil and gas industry versus the building sector. The international organisation of Oil and Gas Producers reports the safety statistics for the whole of the sector annually [1].

The lost time injury frequency, the number of incidents with loss of labour of more than 24 hours per million hours worked, is for the whole of the sector 0.45. This is in sharp contrast to the building industry. The Dutch Investigation Council for Safety reports a LTIF of 33 over the years 2001 to 2011 [2]. Almost two orders of magnitude difference. Admittedly the number for the oil and gas industry is not equal to zero, so accidents do still happen, but it is a marked difference to on the one hand the statistics for that same industry 10 or 20 years ago and on the other hand the present day statistics of the building sector. OGP is counting in their statistics all workers in the industry, both company staff as well as contractor staff. The Safety Council has looked at all workers on the payroll. These data are therefore comparable.

More statistics can be gathered once a deep dive is taken into the annual reports of the various construction companies, the owner companies and suppliers. Unfortunately in that case the data are certainly not comparable. Most of the construction companies report the statistics for their own staff in the annual reports and leave the statistics for their contracted staff conveniently out. So looking at all those statistics will give a wrong and clearly too optimistic impression, but for completeness sake the LTIF figures are summarised in Table 1 for a selection of companies. The companies are listed in alphabetical order.

These statistics do trigger for the experienced safety supervisors another concern. Once there are more than 30 lost time incidents things are bound to get worse. The theory of Heinrich, by now maybe somewhat dated and not always straightforwardly applicable, tells us that a more serious incident is going to happen. This is not a fatalistic view of the world, but the statistics develop in this direction according to the theory. The original theory is published by Heinrich [3] in 1931 in an article title "Industrial Accident Prevention: A Scientific Approach". Heinrich showed in this article that every accident with severe injuries (or worse) is preceded by 29 incidents with a light injury and 300 incidents without injury. This has been graphically represented in Heinrich's triangle.

In 1969 Bird [4] has adapted the ratios to 600:30:10:1 representing incidents without injury, incidents with damage, incidents with light injuries and incidents with heavy injuries. At the moment the process industry is using the ratio 3000:300:30:1 in which also the severity has been adjusted. The top of the triangle nowadays represents the number of fatalities.

Although over 80 years old, the theory of Heinrich is still referred to. Within safety science it is almost seen as a law of nature, although there is also some criticism. Since publishing the theory the number of small incidents has clearly dropped, but the larger or heavy incidents with serious injuries are not declining with the same pace. So preventing the smaller incidents is not the approach to also reduce the larger incidents. The opposite is truer: when a serious incident has taken place, investigation afterwards shows that a number of smaller incidents following a similar pattern have preceded the large incident but with less or without any consequential damage. In these cases some of the barriers between cause and effect have actually worked.

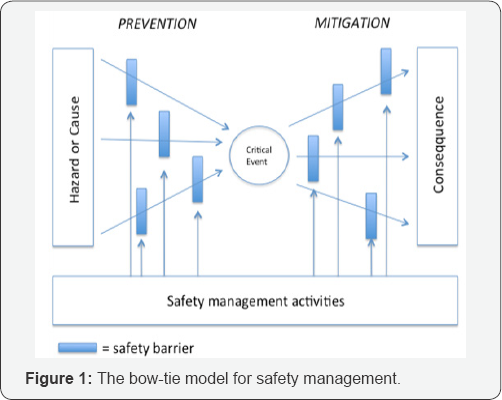

Supported or not the triangle has focussed the attention on the human behaviour, in organising the processes as well as in the execution of work. Since mistakes can always be made, the utmost has to be done to design the processes as far as possible as “fail-safe”. So only focussing on labour safety is not enough, but certainly a first step to improving overall safety statistics. At the end the whole organisation has to be studied in order to operate safely, meaning incident free. A mature organisation will have to be managed on the basis of impending incidents (near- misses) and not only on the basis of actual incidents. And clearly that is a tough job, since these signals are weak and difficult to discriminate between the information overload that the organisation is suffering from on a daily basis (Figure 1).

The thinking in barriers is based on the bow-tie model sometimes also called the Swiss cheese model [5-7]. The model combines the concepts of cause, event and effect. Every event can have a number of causes and once the event is triggered it can lead to a variety of effects. The bow-tie model is highly structured and a nice way to schematically represent the whole process. The emphasis in the bow-tie model is on the barriers, between cause and event and between event and effect. Preferably in this approach the intent is to prevent an event to happen by throwing in a number of barriers to prevent the cause triggering the event. Those barriers can be physical, but also behavioural.

In case an initial barrier did not work or was omitted, the cause might trigger the event and the next set of barriers is meant to prevent the consequences of the event, the effects, by throwing in barriers between event and effect. To give a simple example, think about driving a car. Driver training, traffic rules, speed limits are all barriers for preventing collisions. The safety belts and air bags and the like are all barriers to prevent injuries once an event, a collision, has happened. Modern incident investigation is aimed at identifying the barriers and whether they have worked or not. With the benefit of hindsight an incident can then be followed up by improving the safety systems in case a barrier was missing or retraining staff in case a barrier was broken deliberately, to prevent the accident from happening again.

The two key words in the bow-tie model are: barrier and scenario. The origin of the term barrier is probably associated with the energy barrier model that can be traced back to Gibson [8]. The term safety barrier can now be found in regulations, standards and scientific literature [9]. The bow-tie model visually combines fault tree analysis on the left side and event tree analysis on the right side. The critical event sits in the middle. Between the critical event and the two ends, barriers can be put in the paths that run from cause to event to affect, the so called scenario. For a critical event there can be multiple causes, consequences and scenarios [10]. The scenarios are the paths/arrows going through the critical event. The bow-tie model emphasises the importance of managing the barriers. This highlights the fact that accidents can be prevented as long as the barriers are managed in the proper way, from design, via specification, construction to operation, maintenance and final abandonment. Another solution could be to totally change the working method so that the scenario does not apply anymore.

The most important step towards an improved safety performance is the change in the behaviour of both staff and management. Many companies have accepted that and have developed their own ways of changing behaviour. Programmes to reach the hearts and minds of staff are examples of this approach. The most important message is that the bigger the belief that safety is not just a coincidence, an act of luck, but a dedicated choice that is highly dependent upon the interaction between staff. Changing the behaviour is not something that can be done overnight. The company Dupont is a good example that this can be done, but it has taken something like 20 years to reach the excellent safety statistics that they have today.

The Dupont Bradley curve [11] is a good example of the growth process that staff and management have to go through to meet the objectives: a goal of zero incidents is possible. In the words of Dupont: “In a mature safety culture, safety is truly sustainable, with injury rates approaching zero. People feel empowered to take action as needed to work safely. They support and challenge each other. Decisions are made at the appropriate level and people live by these decisions. The organisation, as a whole, realises significant business benefits in higher quality, greater productivity and increased profits." The Dupont Bradley curve supports the understanding of the mind- shift that is required by all involved and the actions that go with this shift to realise a mature safety culture. The attitude changes gradually from reactive, via dependent and independent to interdependent. In the final stage people feel ownership for safety and take responsibility for themselves and others as they are firmly convinced that real improvement can only be realised as a group.

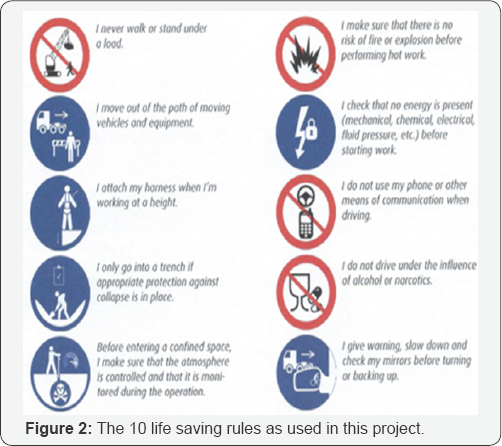

Finally, based on experience and a thorough analysis of incidents, accidents and fatalities that have happened in the process industry over the last few decades, has led to a number of so-called life saving rules. The most important causes of accidents and fatalities have been translated in this set of rules. You could call it the do's and don'ts of working safely in the industry. These rules originate from the oil and gas industry and as a consequence care has to be taken when applying these rules in a different industry. For instance the main causes of fatal incidents in the construction sector can be slightly different than the main causes of fatalities in the process industry. So other rules will apply. Workers should be able to relate to the rules and recognise them otherwise it will be counterproductive. In some instances translating them into a number of different languages is a necessity when the majority of the workforce consists of workers coming from abroad (Figure 2).

The project

The project and its participants will be kept anonymous. Reason for doing that is that the authors would like to tell a more generic story. Coming up with a detailed story with all the project specifics might put people off and prevent them from looking into the real learning. The article aims to enable other project managers to adopt or adapt the learning to their own project and special circumstances. Furthermore, by naming companies, contractors, subcontractors and suppliers, the wrong impression might be given. The project is not the result of individual behaviour or excellence, but a result of a joined effort of a number of companies who worked closely together to reach this result.

The project under study is an infrastructural project somewhere in the Netherlands. The total capital expenditure was 300 million Euros and the planned duration was 54 months. The works were a combination of civil works, technical installations, road works including the commissioning and start-up. The principal was a limited company with the regional government as their single shareholder with the director and the project manager as the only two staff members. All other staff of the principal's project team was direct hires and freelance professionals hired for and by the project team and 2 staff seconded by the regional government. The works were tendered as a design and construct contract and rewarded at the lowest price. The final construction company selected was a consortium consisting of four individual companies. The principal stated as one of the tender requirements that the installation contractor should be an integral part of equal partner in the consortium and would be participating from day one. Most often in these types of infrastructural projects, the start-up of the product is seriously delayed because of the installations. By having them already onboard from the word "go" this risk was recognised, controlled and minimised.

The project manager originated from the process industry where he learned the trade. He had previous experience in executing similar projects for the regional government. The safety statistics of the earlier projects made him and the director look for a better way of managing this project, with less incidents, better statistics and an overall better project performance. He came to the conclusion that in order to deliver a better project performance, safety had to be managed. As a consequence right from the start of the project safety got priority. Quite often safety is seen as a responsibility for the contractor, which is indeed an important part of the Dutch labour laws. But the principal took also a part of the responsibility in this project. The principal declared the boundary conditions within which the works will be executed. The project manager and the director challenged the contractor's right from the start to work safely and stated their ambition to have no fatalities and a LTIF of less than 5 at the end of the project. That clearly requires an attitude that assumes that accidents and incidents are not a part of the job, that they are not just a reality in civil construction projects. They made safety a deliberate choice. The stronger the conviction that safety is not just a coincidence but the result of interaction between staff, the less accidents will happen. So the intent was to shift to the right on the Dupont Bradley curve to a more interdependent behaviour towards safety.

It was the firm belief of both the director and the project manager that by getting the safety behaviour right the project would also perform much better. That has been the guiding principle for the project management. By thinking in risks that could jeopardise the execution you are dealing with safety, but as a next step you also translate these risks into the planning and in that way you also control quality, costs and time. So safety first has more than one meaning for this project.

The practical side of changing behaviour

After selecting the successful bidder, on the lowest price, principal and project manager made an incentive available for improved safety performance of the project. This was deliberately done after the award so that the various contractors would not price in that incentive in their bids. So in this situation the price of the contract was clear and an additional incentive was put on the table for improved safety. The second step that was taken that is essential for the success of the project is that the principal, the project manager, the project team of the principal and the project team of the consortium were all housed in one barrack at the construction site. They were sitting next to each other under one roof and sharing the social areas, canteen and the entire infrastructure required for a seamless execution. They were literally acting as one team [12]. In a recent study on collaborative relationships between owner and contractor in capital project delivery [13], it was concluded that these owner-contractor relationships should be based on affective trust, shared vision, open and honest communication and senior leadership involvement. One could argue that these are indeed the essential elements in the successful cooperation in this project as well.

Safety performance can be influenced at a number of levels and in all phases of the project:

a. Design: In the design phase attention should already be given to safe operations after completion and safe execution during the construction phase;

b. Technical: The materials and the tools that are used during the construction have to be safe and fit for purpose;

c. Organisation: Procedures have to be in order, correct, clear and workable and have to be complied with;

d. Behaviour: Staff has to work safely with all the tools and procedures at their disposal.

The technical and organisational steps can be realised quite simply. The most important safety rules, the ten life saving rules were made clear to all staff (and visitors), when entering the construction site, and they are spread around the construction site and the office building as a constant reminder. Furthermore, there is a detailed system of work instructions for the construction site. They start with instructions at the entrance gate and are extended to detailed work instruction and risk inventarisation.

Also a Last Minute Risk Assessment, to be done just prior to starting the work, is an essential part of the safety culture on site. Close attention is also paid that the correct and safe materials and tools are being used. When the materials or tools are not in order the work will be stopped and only continued once the right materials and tools are available. This is typically a role for the contractors because these are already prescribed in the labour legislation. Unfortunately not every site adheres as strict to these rules as should be done. On this project everything is checked and stopped when necessary.

Strict compliance is adhered to. However, influencing the behaviour is the most challenging part of the safety journey. When you are able to influence the behaviour, you will make a difference. Looking back at the situation in Dupont it took them 80 years to go from a LTIF of 80 in the 1920's to a LTIF of 0.2 in 2000. So much time is normally not available in a project. So different measures have to be taken. Rewarding the right type of behaviour and punishing the wrong behaviour can accelerate behavioural change. This project has chosen the positive approach. An incentive system has been set-up after the finalisation of the contract. The incentive system knows a few reward levels: the consortium level, the individual workers/ teams and the staff in general.

A word of warning is justified at this place. It is a good thing to make sure that everybody is working towards the same goal. That all noses are pointing in the right direction. But you have to be absolutely sure that that holds for everybody. Principals have a tendency to crank up the pressure in order to be ready on time. This will always go at the expense of the safety when the contractors are still too much reactive, situated on the left side of the Bradley curve. Short cuts are taken, precautions forgotten and accidents are waiting to happen.

The consortium could earn a safety bonus every month that could total up to one million over the course of the project. The monthly percentage was established on the basis of safety plans and inspections and observations on the construction site. Those inspections were again executed together. Small and large issues were addressed and reported. Small because many small issues can lead to a disaster conform the Heinrich triangle. By controlling the small, it was believed that the big issues could be prevented. Three types of issues were recognised, so called A, B and C observations. A C is a small imperfection, a B is something unsafe but not immediately dangerous, but to be corrected before it could grow out of control. An A is an imminent danger. Work will have to be stopped and corrective actions taken.

The scores observed during the inspection were the basis for calculating the bonus. The procedure also contained a form of punishment. A lost time injury would cost the consortium 50.000 Euro and a fatality half a million. That would mean that even in the worst case of a fatality the consortium could still earn the bonus if the rest of the work was done well and safe. For the external experts that we consulted for their opinion on the overall approach of managing this project, this was actually a sore point. With this penalty system it looks like the principal is putting a price on a human life, which could never be the intent. Furthermore, they found that it is remarkable that the principal is rewarding something that is a legal requirement anyhow.

In order to make sure that not only the consortium would benefit from a safe execution on a monthly basis an excelling worker or an excelling team in the field of safety would be put in the limelight in the monthly safety meetings. They would receive a "safety certificate" and a money award. The certificate would be granted after close consultation between the principal, his project team and the consortium and officially handed over in the presence of all staff. This became something to strive for. Every team, every worker, every company wanted to receive this reward. In this way safety and safety performance became a living subject for all workers. People were proud to receive a certificate, and actually the management of the subcontractors came to the meetings to receive the awards for the company. It clearly attracted attention.

But safety awards alone were not enough to change the culture. The consortium issued strict rules and procedures for the management of safety. Subcontractors with more than 20 staff on-site had to have a safety advisor. The supervisors on the construction site had to be able to communicate in Dutch, English or German and to instruct their staff in their own language. In this way it was made sure that language would not pose a barrier to improved safety performance.

Finally, all workers received a present when the monthly safety score would be above 75%. These statistics were made visible in the canteen and people kept a close track on the performance in this way. A simple safety thermometer was developed consisting of a number of transparent tubes for each month and balls representing the inspections. Above 75% the balls would turn green, between 50 and 75% the balls were blue and under 50% the balls would turn red. The presents were simple, for example a safety hammer or are freshment. By handing out the presents there was again a moment to focus on safety. Every opportunity to focus on safety has been taken. All workers of the principal had full basic safety certification. Meetings, periodicals and a website were utilised to spread the message. No escape possible. Also externally the message was communicated, not only to inform other projects about this approach but also because the internal acceptation becomes bigger once stimulating external reactions are received. Not only have presentations been given to other projects, they have also been invited to visit the construction site and experience the approach via direct contact with the workers.

The approach taken by the principal and his project team has definitely paid off. The project was delivered with a safety statistic that was one order of magnitude better than the reported statistics in the building construction sector. The LTIF for the project was 3.1. But that was not the only accomplishment: the project was delivered 6 weeks ahead of schedule and the budget was under spending by 25 million Euros or 8%. A truly remarkable result. Not yet a zero incident result but certainly showing that also projects in the civil infrastructural industry can be delivered safely, as long as the intent and the belief that such a result is feasible is there and communicated, advocated and shown throughout the whole project.

Evaluation and Analysis

In the final stages of the execution of the project the authors have had the opportunity to interview a number of involved staff of bothproject teams, the construction manager, the principal and the management teams of the parties making up the consortium. Across the board the experiences are positive. There is of course pride in the result obtained. Some of the remarks of the members of the management teams clearly indicate to us that they still have a long journey ahead of them. Their behaviour is still highly reactive and clearly positioned on the left side of the Dupont Bradley curve.

A lot of the credit is given to the project team of the principal. According to all management teams they made it happen and all management team members are uncertain whether the same results can be realised with a different principal. They openly advocate now that they see the benefits but they are not certain yet that they can pull it off on their own. ]

The principal and his project manager have clearly taken the initiative in this project. The fact that they were so convinced that an incident free project is feasible has made a world of difference. They have shared their ambition, showed their beliefs and conviction and in this way pulled along with them all the individual management teams. This clearly resonates in the interviews and discussions with the managers of the consortium and their parent companies. The interviewees admit wholeheartedly that making the incentive available after awarding and signing the contract was a wise decision. In any other situation the price of the incentive would have been absorbed in the bid and would not have had the same power as it now had. They have shown together that safe operations in the civil construction industry are feasible and they do believe that the incentive is not a necessity to make this happen but it definitely eased the process.

They all support the fact that the increased attention for safety has elevated the whole execution of the project to a different, higher level. It is not only the safety statistics that show an improvement, the whole management and execution of the project has improved, with visible and positive results. A proper work preparation is seen as a necessary condition that results in a more stable and prepared work place and thus a safer workplace.

They have seen now what is possible and it is up to them to continue this behaviour on the next project of their company together with the same companies or in different constellations as theyappear in projects. They owe it to their staff and shareholders to continue the approach. The building sector is different from and possibly more dynamic than the process industry. But that offers opportunities for innovation and improvement. Unfortunately these innovations are hardly ever taken in the field of safety. When the companies are not able to learn from this approach and hold on to it, then they will never shift to the right side of the Bradley curve. And that is they should be. That is what staff should be demanding.

Conclusion

The learning of the project understudy is loud and clear. What will happen with this experience in the near future is very uncertain. The management teams of the consortium partners, the contractors that have to carry the torch, are somewhat ambiguous in their approach: they say the right things, but their actions should show their change in behaviour. As long as in the building industry in the Netherlands fatalities are still accepted as a given, then there is still a long road ahead. Contractors' main purpose in life seems to be making money, logically. But not only the contractors are to blame, not all principals clearly steer the contractors on the basis of their legal responsibilities to organise the works in such a way that it is executed safely Instead the principal is paying a bonus to work safely. That is the world upside down, but as long as the contractors are as reactive as they are, this probably will work. From our other studies and observations we are convinced that as long as the principal steers on the legal requirements (safety behaviour), quality, costs, planning and work preparation the works will be executed more efficiently (less rework that was already budgeted for) and the final performance will be that the quality of the work delivered and the accompanying safety performance will be better. In short, the contractor will have worked more efficiently and saved money as a consequence (profit). In our view, safe working is efficient working and will lead to additional profit.

The approach as described in this case study is very much in line with results of earlier studies [14] into improving labour safety. In that study 17 improvement trajectories have been evaluated. The most important lesson from that study has been that it is not only about reward and punishment, but it is about holding the dialogue: a lively dialogue about safety in all layers and between all layers of the organisations that are working together. The ultimate aim of these dialogues or interventions is that all involved are learning from it, that is the central theme. A few of the tips from this study have clearly been practised in the present project. The involvement of senior management is essential, rewarding good behaviour, learning from each other and advertising results are some of the practices.

The present project team has handled a number of things very well. However, it should be realised that every project might need a different approach. Solutions fitting the situation will have to be used and the tools developed for the specific industry should be used. One should also realise that small companies are not just small “big companies” and small projects are different from large projects. Building a road is different from building a house, and painting works are clearly different from installation works. The organisation is different so the work circumstances have to be arranged differently. As a consequence, a transfer of practice from one industry to the next will not automatically work. One size does not fit all and the approach has to be fit for the purpose and fitting the industrial environment.

The main learning that can be and should be transferred to other projects are: 1) an integrated front-end development with all the main players present from the start (the installation contractor as equal partner in the consortium); 2) all the parties acting as one team throughout the whole project and 3) senior management commitment from all parent organisations for the approach chosen. These learning are generally applicable and should be practised more by other projects, big or small, to guarantee a better project performance in the future.

Acknowledgement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors would like to thank the project team and the management board for their cooperation in and openness during the interviews. Without their support this article would not have been feasible.

References

- (2013) International Association of Oil & Gas Producers. Safety Performance Indicators-2013 data (OGP Data Series).

- Loo Mvan H, lpenburg DC, Verhallen PJJM (2013) Willeboordse EV in perspectief. Onderzoeksraad voor Veiligheid, Den Haag.

- Heinrich HW (1931) Industrial accident prevention: a scientific approach McGraw-HiII, New York.

- Bird FE (1992) Germain GL Practical Loss Control Leadership. Loganville Georgia; International Loss Control Institute

- Ale BJM, Bellamy LJ, Papazoglou IA, Hale A, Goossens L, et al. (2006) ORM: Development of an integrated method to assess occupational risk, International Conference on Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management, ASME, New York , US, p.10.

- Hale AR (2003) Safety management in production. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing 13(3): 185-201.

- Hale AR, Bellamy LJ, Guldenmund F, Heming BHJ, Kirwan B (1997) Dynamic modelling of safety management. Advances in Safety and Reliability: ESREL 1997 International Conference on Safety and Reliability, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Gibson JJ (1961) The contribution of experimental psychology to the formulation of the problem of safety-a brief for basic research. Behavioral Approaches to Accident Research, Association for the Aid of Crippled Children, New York, USA, p. 77-89.

- Sklet S (2006) Safety barriers: Definition, classification and performance. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 19(5): 494-506.

- Ale BJM (2007) Causal model for air transport safety interim report Risk Centre TU Delft.

- Dupont Bradley (1995) Dupont.com website, proprietary system helped enable safety success within DuPont, and for their clients around the world.

- Bakker HLM, de Kleijn JP (2014) Management of engineering projects- People are key.

- Suprapto M, Bakker HLM, Mooi HG, Moree W(2015) Sorting out the essence of owner-contractor collaboration in capital project delivery. International Journal of Project Management 33: 664-683.

- Guldenmund FW (2011) Hale AR Weten wat werk tien tips voor de vergroting van arbeids veiligheid Arbo oktober, pp. 22-25.