Abstract

Genetic advancements have revolutionized the landscape of pediatric cardiology by enhancing our understanding of the molecular and hereditary basis of congenital heart disease (CHD) and cardiomyopathy. With the advent and integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS), whole exome sequencing (WES) and PCR. Clinicians now have powerful tools for identifying pathogenic variants that contribute to a variety of pediatric cardiovascular conditions. This narrative review explores the evolving role of genetic testing in pediatric cardiology, highlighting its applications in diagnosis, individualized management, and risk stratification. this review also throws light on functioning and contribution of genetic sequencing techniques in pediatric cardiology. The ability to identify the variants early in life offers a significant opportunity for timely intervention, prevention of complications, and improved long-term outcomes. In clinical practice, genetic findings are increasingly influencing patient management, including pharmacologic strategies, surveillance protocols, and decisions regarding the implantation of cardiac devices in cases of arrhythmias.

Despite these advances, challenges remain. A major barrier to clinical implementation is the interpretation of variants of uncertain significance (VUS), which requires a deep understanding of gene-disease associations and often requires additional studies. Moreover, ethical dilemmas such as the management of incidental findings, issues of informed consent in pediatric populations, and the psychological impact of genetic diagnoses on families demand careful navigation. These concerns require the need for multidisciplinary collaboration between cardiologists, geneticists, and genetic counselors. The current variability in access to genetic testing, both geographically and socioeconomically, further highlights the necessity of establishing equitable and standardized protocols for genomic integration in pediatric care. The evidence reviewed supports the routine incorporation of genetic testing into the diagnostic workup of children with CHD. As precision medicine becomes increasingly central to cardiovascular care, there is a growing need for clinician education on genetic principles and data interpretation. Ultimately, the application of genetic insights in pediatric cardiology holds the promise of transforming patient care from reactive to proactive, with earlier diagnosis, tailored therapy, and better long-term quality of life. Broader adoption of these technologies, along with continued research and policy development, will be essential for translating genetic discoveries into tangible clinical benefits for children with heart disease.

Key words:Cardiology; Paediatrics; Congenital heart disease; Genetic Syndrome; Cardiomyopathy; Next-generation sequencing; Variants of uncertain significance; Diagnosis; Congenital heart Illnesses; Anatomy; Physiology; Geneticists; Genetic counselors

Introduction

Determining the molecular features of various heart problems requires an understanding of the genetic causes of cardiomyopathies and other congenital heart illnesses. Our understanding of the molecular specifics underlying these disorders has advanced significantly as a result of investigating these hereditary origins. Understanding the genetic and molecular patterns that account for the causes of cardiomyopathies has replaced the previous emphasis on the anatomy and physiology of the heart. Contemporary genomic technologies present an excellent opportunity for early diagnosis, identifying problems before they manifest clinically. However, the complexity of genetic information and the rapid pace of study are posing problems for the profession.

Due to its critical role in early disease detection and individualized treatment, genetic testing is transforming pediatric cardiology. Its significance in detecting congenital and acquired heart diseases in their early stages is shown by numerous scientific studies. Novel therapies are made possible by this early recognition, which enhances clinical results and avoids problems. The results highlight how genetic testing might inform individualized treatment regimens according to a person’s genetic composition, improving the effectiveness of therapies. Additionally, genetic markers are essential for risk stratification because they offer information that makes it possible to make more accurate predictions about the chance of acquiring cardiac problems. All of these data points to genetic testing as a crucial instrument influencing pediatric cardiology’s future and offering early, accurate, and customized patient care.

Genetic testing is proving to be a valuable tool in routine

pediatric cardiology practices, particularly in the diagnosis and

management of various cardiomyopathies in children. Significance

of genetic approach in cardiology is as:

• Determining Genetic Causes: Genetic testing helps

in determining the precise genetic origins of childhood

cardiomyopathy. This is necessary for a definitive molecular

diagnosis, which enables medical practitioners to comprehend

the underlying genetic components causing the illness.

• Growing Clinical Genetic Testing: This availability gives

medical professionals the ability to incorporate genetic data into

standard procedures, providing a more thorough approach to

pediatric cardiology.

• Role in Diagnosing Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: Genetic

testing has been useful in helping medical professionals to better

understand restrictive cardiomyopathy and adjust treatment

regimens by examining the genetic components that contribute

to the condition.

• Etiological Diagnosis for Pediatric Cardiomyopathies:

Determining the diagnostic and treatment paths for pediatric

cardiomyopathies requires etiological diagnosis, in which genetic

analysis is essential [1-4]. Understanding the condition’s genetic

foundation enables a more focused and efficient treatment

strategy, which may enhance patient results.

Based to this futuristic perspective, genetic testing is leading the way in changing the scenario of pediatric cardiology. Future developments in cutting-edge techniques and technologies promise a revolution in this sector. The collaboration of pediatric cardiologists and geneticists is to be emphasized, with a focus on cooperative efforts. Along with improvements in research and diagnosis, this collaboration promises a more thorough and allencompassing approach to pediatric cardiac health management.

Discussion

Significance of Genetic Testing in Pediatric Cardiology

Managing pediatric cardiac disease presents a multifaceted challenge for emergency physicians, given its tendency to manifest symptoms resembling other systemic conditions.

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are of significant importance in pediatric cardiology. Previously undiagnosed cardiac diseases in children can mimic other conditions, making early identification and treatment crucial. Electrocardiographic screening in childhood allows for the early detection and treatment of life-threatening arrhythmic heart diseases [5-8]. Dilated cardiomyopathy in the pediatric age group is associated with heart failure, and early diagnosis is essential for appropriate management. High blood pressure in childhood and adolescence, often associated with sedentary lifestyles and obesity, can lead to cardiovascular risks in adulthood, emphasizing the need for early interventions [9]. Early diagnosis of congenital heart disease through fetal echocardiography offers advantages such as parental counseling and optimized perinatal care, reducing mortality and morbidity [10]. Through a comprehensive retrospective chart review spanning 5.5 years,36 cases were identified, indicating one patient per 4838 pediatric ED presentations. The spectrum of chief complaints, triage categories, and diagnoses in pediatric patients encompasses undiagnosed congenital lesions, acquired cardiac disease, dysrhythmias, and infectious heart diseases. Noteworthy is the significant requirement for surgical intervention at 22%, coupled with a 6% mortality rate, underscoring the high-risk nature of these cases. Despite their collective occurrence at a noteworthy rate, individual instances are infrequent, posing a challenge to pattern recognition for clinicians. Effectively managing these cases necessitates a keen index of suspicion and exceptional clinical acumen to facilitate timely diagnosis and optimal care within the pediatric emergency department [7].

Risk stratification plays a crucial role in familial cardiovascular health. It helps identify individuals who are at high risk for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and enables personalized prevention and treatment strategies. Various approaches have been proposed for risk stratification, including the use of risk scores, genetic analysis, and biomarkers. The in-depth analysis of risk stratification for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) presented on The College of Family Physicians of Canada emphasizes the critical evaluation of both traditional and non-traditional risk factors. With a focus on a comprehensive methodology, the page advocates for a patient-centered approach, emphasizing the significance of shared decision-making and effective communication. Moreover, it explores the substantial influence of risk stratification on treatment decisions, including key elements such as lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy [11]. Genetic testing plays a pivotal role in the landscape of pediatric cardiology, exerting a profound influence on the strategies employed for treatment and interventions. One cannot overstate its significance in the etiological diagnosis of pediatric cardiomyopathies, offering a personalized gateway to diagnostic and therapeutic pathways [12]. A noteworthy facet is its capacity to unveil molecular diagnoses in pediatric patients grappling with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), even in the absence of overt clinical suspicions of a genetic syndrome. This not only broadens our comprehension of the disease but also extends its impact well beyond the realms of mere diagnostics or prognostics. This extension encompasses the formulation of disease-specific guidelines and the determination of eligibility for participation in clinical trials [13].

Within the realm of pediatric cardiovascular diseases, clinical genetic testing emerges as a pivotal linchpin, playing a crucial role in informing diagnosis, guiding clinical management, and forecasting prognosis. However, it is incumbent upon us to recognize a critical gap in the existing landscape: a conspicuous absence of pediatric-focused guidelines. This underscores a compelling need for further dedicated research tailored to this particularly vulnerable population [14]. The pivotal role of genetic testing becomes even more pronounced in the sphere of pediatric inherited cardiomyopathies and channelopathies, where conventional evaluation methods often fall short of establishing a conclusive diagnosis. Yet, a judicious and cautious approach is warranted due to the absence of uniform recommendations and the potential psychological impact associated with genetic diagnoses [15]. Unveiling its multifaceted utility, genetic testing also proves to be instrumental in the investigation of survivors of pediatric sudden cardiac arrest. Beyond providing valuable diagnostic insights, it exercises a tangible influence on longterm outcomes and shapes critical treatment decisions [16]. The expanding role of genetic testing in pediatric cardiology not only highlights its current significance but also underscores the pressing need for comprehensive research and guidelines meticulously tailored to address the unique challenges presented by this particularly sensitive patient population.

Genetic Syndromes in Pediatric Cardiology Down syndrome and its cardiac anomalies

Down syndrome (DS) stems from the trisomy of chromosome

21 (Hsa21) and intertwines intricately with congenital heart

defects (CHD) [17-20]. A noteworthy statistic discloses that

around 40-60% of infants identified with DS concurrently manifest

CHD. This prevalence underscores the repercussion of Hsa21 gene

overexpression, with a specific emphasis on those genes entangled

in the organization of the extracellular matrix (ECM), acting as a

probable catalyst in the genesis of CHD. The most common form

of CHD observed in Down syndrome is atrio-ventricular Septal

Defect [17]. Triplication of chromosome 21 genes is a significant

factor contributing to the incidence of congenital heart defects

(CHDs) in Down syndrome (DS). The extra copy of chromosome

21 leads to:

• an increased dosage of genes involved in cardiac

development, which can disrupt normal heart development and

contribute to the occurrence of CHDs in DS.

• The specific genes on chromosome 21 that are triplicated,

such as GATA1, DYRK1A, and ERG, have been implicated in cardiac

development and have been associated with CHDs in DS.

• The triplication of these genes can lead to dysregulation

of signaling pathways involved in cardiogenesis, affecting the

formation and function of the heart. The increased dosage of

chromosome 21 genes, along with interactions with other genetic

and environmental factors, contributes to the variable phenotypic

expression of CHDs in DS [17].

The genetic architecture of CHD in DS is complex, involving multiple genes and genetic events. Further research is needed to fully understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the cardiac anomalies in DS.

Turner’s syndrome and its cardiovascular ties

Turner syndrome (TS) is a genetic disorder characterized by

the partial or complete absence of an X chromosome in females.

It is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases

(CVD) [19]. Cardiovascular manifestations in Turner syndrome

(TS) include:

• Congenital heart diseases, such as coarctation of the

aorta, bicuspid aortic valve, and atrial septal defects.

• Acquired heart diseases, including acute aortic

dissection, stroke, myocardial infarction, and hypertension.

• A higher risk of aortic dilation and aortic valve

abnormalities, which can lead to aortic regurgitation and stenosis.

• Increased prevalence of atherosclerosis and early

development of coronary artery disease.

• Impaired left ventricular function and diastolic

dysfunction [18].

22q11.2 deletion Syndrome (22q11.2 DS)

The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, characterized by an estimated prevalence of 1 in 4–6,000 live births, exhibits a spectrum of features encompassing facial dysmorphia, hypocalcemia, palate and speech disorders, feeding and gastrointestinal issues, immunodeficiency, recurrent infections, neurodevelopmental, psychiatric disorders, and congenital heart disease. Among individuals with the syndrome, approximately 60-80% manifest cardiac malformations, particularly conotruncal defects that manifest from birth. These heart problems encompass conditions like tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect, truncus arteriosus, and interrupted aortic arch. The likelihood of having the 22q11.2 deletion in the presence of conotruncal heart issues varies significantly, ranging from 4.3% to 100%, contingent upon the existence of other complications such as a weakened immune system or distinctive physical features [21]. Fortunately, advancements in genetics, diagnostics, and medical procedures have significantly improved outcomes for individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and associated heart problems following surgery [22]. Notably, approximately 19% of children exhibiting both heart issues and distinctive facial features are diagnosed with the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome [23]. Among the various cardiac complications associated with 22q11.2 deletion, conotruncal defects and aortic issues are the most prevalent [24]. While individuals with 22q11.2 deletion and heart problems do not exhibit a heightened risk of mortality during surgery, they may encounter heightened challenges around the time of the surgical procedure]. Recent guidelines advocate for screening 22q11.2 deletion in patients with specific cardiac malformations, such as tetralogy of Fallot, truncus arteriosus, interrupted aortic arch type B, conoventricular septal defects, and isolated aortic arch anomaly. Early identification, even in neonates or infants lacking apparent syndromic features, enables timely parental screening for reproductive counseling and comprehensive evaluation of cardiac and noncardiac features [25].

Other Lesser-Known Genetic defects in Pediatric Cardiology

Pediatric heart issues cover a lot of different genetic problems. Some lesser-known ones include Noonan’s and cardiofaciocutaneous syndromes (CFCS). These conditions not only affect the heart but also cause developmental delays, short stature, and physical differences [26]. The most common cardiac abnormality in Noonan syndrome is pulmonary valve stenosis, which is seen in a high percentage of cases. Other cardiac abnormalities include atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [27] [28]. The cardiac phenotype in CFCS includes cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias. In some cases, CFCS can also present with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [29]. In the area of pediatric cardiomyopathies, a myriad of phenotypes can emerge, often rooted in genetic causes such as mutations in sarcomeric proteins [30]. Extensive genetic testing of children suffering from cardiomyopathy has revealed that pathogenic variants predominantly reside in genes encoding sarcomere proteins. Some specific variants have even been linked to more severe clinical outcomes [31,32]. Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in children, too, has genetic origin. Mutations in genes governing the structure or function of sarcomere, desmosomal, and cytoskeletal proteins have been implicated in pediatric DCM cases. Notably, the titin (TTN) gene is a big player, with changes found in a good number of cases [33].

The Genetic Toolkit

Chromosomal Microarray Analysis

The chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), particularly the micronucleus assay, is an essential component of contemporary cytogenetic testing methodologies. CMA is a technology used for the detection of clinically-significant micro deletions or duplications, with a high sensitivity for submicroscopic aberrations [30]. The micronucleus assay, distinguished for its sensitivity and reliability, occupies a pivotal position in genotoxicity assessment. The micronucleus assay, often used alongside the chromosomal aberration test, provides valuable insights into genetic alterations caused by various compounds [31]. It is able to detect changes as small as 5-10Kb in size - a resolution up to 1000 times higher than that of conventional karyotyping. Micronuclei serve as clear indicators of cytotoxic damage, revealing chromosomal aberrations and genetic instability from environmental factors [32]. Advancement in CMA has led to identification of new microduplication and microdeletion in patients with Intellectual Disability (ID), Global Developmental Delay (GDD), epilepsy and congenital anomaly. CMA has become a first-tier test in the evaluation of individuals with ID and GDD. CMA can also detect well known microdeletion syndromes such as chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome.

This assay has become a key tool in both research and regulatory contexts, advancing our understanding of genotoxicity. With the ability to be performed in vitro or in vivo, the assay benefits from automation technologies like image analysis and flow cytometry, making it adaptable and efficient [34]. Its integration into biomonitoring efforts strengthens our capacity to evaluate occupational exposure to genotoxic substances and improve workplace safety measures.

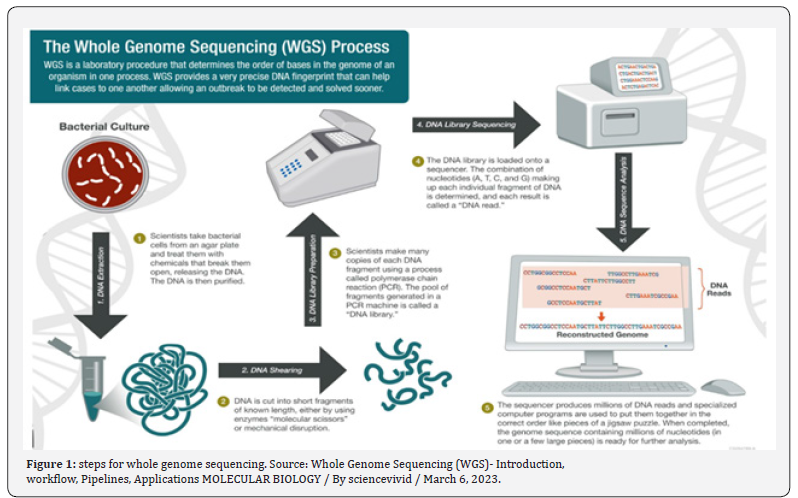

Next-Generation Sequencing Techniques

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) encompasses cutting edge DNA and RNA sequencing methodology designed to efficiently and comprehensively analyse genetic material. Within this field, Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) are prominent methodologies. WES selectively targets the protein-coding regions, or exons, of the genome, whereas WGS offers a comprehensive analysis of both coding and non-coding regions, serves as a guiding force in shaping diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for pediatric cardiomyopathies, facilitating the implementation of personalized and precision-based treatment modalities.

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) can be used in the genetic approach for pediatric cardiology to diagnose and understand the underlying causes of pediatric cardiomyopathies. Pediatric cardiomyopathies are rare and heterogeneous diseases with diverse clinical presentations and etiologies [35]. Genetic analysis, including WES, plays a crucial role in identifying the genetic substrate of these diseases, which is essential for accurate diagnosis, prognosis, and personalized treatment [36]. WES allows for the analysis of the entire exome, which includes protein-coding regions of the genome, using next-generation sequencing technology [37]. This comprehensive approach enables the identification of pathogenic coding variants in known cardiomyopathy genes, as well as non-coding variants that regulate gene expression and function [38- 39].

WES is done by following steps:

• WES starts with the extraction of DNA from the patient’s

sample, followed by the enrichment of the exome using capture

probes that specifically target these regions.

• The enriched exome is then sequenced using nextgeneration

sequencing (NGS) technology, which generates

millions of short DNA sequences.

• These short sequences are aligned to a reference genome,

and the resulting data is analyzed using bioinformatics tools to

identify genetic variants, such as single nucleotide variants (SNVs)

and small insertions or deletions (indels).

• The identified variants are then compared to databases

and literature to determine their potential clinical significance

[35].

WES can help in the diagnosis of genetic diseases by identifying disease-causing variants in known genes or by discovering new genes associated with the condition. It is particularly useful for conditions with genetic heterogeneity, where multiple genes can be responsible for the same phenotype. WES can also be used for cascade screening in family members of the (Figure 1) proband and for reproductive planning [35]. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) can be used in the genetic approach for pediatric cardiology by identifying both protein-coding and non-coding variants that contribute to cardiomyopathy (CMP)[35-37]].Whole genome sequencing (WGS) confirmed causal variants previously identified on clinical genetic testing but also detected additional protein-coding variants, cryptic splice site variants, and copy number variants in CMP genes.WGS also identified patients with rare, functionally active high-risk regulatory variants in known CMP genes and patients with high-risk LoF variants in additional candidate CMP genes [35]. WGS allows for the analysis of the entire genome, providing a comprehensive view of genetic variations. In pediatric CMP patients, WGS has revealed pathogenic coding variants in known CMP genes, as well as high-risk loss-offunction variants in novel cardiac genes [38-39]. Additionally, WGS has identified high-risk regulatory variants in promoters and enhancers of CMP genes, particularly in genes involved in α-dystroglycan glycosylation and desmosomal signaling.

PCR amplification

PCR amplification is a useful tool in pediatric cardiology for the detection of viral infections and copy number variations (CNVs) associated with congenital heart disease (CHD). Several studies have shown the prevalence of viral DNAemia in children with myocarditis, with PCR positivity being higher in infants compared to older children [40]. PCR can aid in the diagnosis of viral infections in heart transplant recipients, especially in cases of late-onset rejection or chronic rejection [41]. PCR is a sensitive and specific technique used to detect and amplify small amounts of viral nucleic acid in a patient’s blood sample, allowing for the identification of viral infections. The study mentioned in the provided sources found that infants with clinical myocarditis had a high rate of blood viral positivity when tested using PCR, suggesting that viral blood PCR may be a useful diagnostic tool in identifying patients who would potentially benefit from virusspecific therapy [41]. Additionally, PCR can be used to screen CHD patients for CNVs in specific genomic regions, leading to early diagnosis and identification of syndromic patients [40-41].The technique of PCR involves multiple steps, including denaturation, annealing, and extension, to amplify specific regions of the viral genome .PCR uses specific primers that bind to complementary sequences in the viral DNA or RNA, allowing for the selective amplification of viral genetic material .The amplified viral DNA or RNA can then be detected using various methods, such as gel electrophoresis or fluorescent probes, to confirm the presence of the viral infection.

Steps for PCR:

• Denaturation: The DNA sample is heated to separate the

double-stranded DNA into single strands.

• Annealing: Short DNA primers that are complementary

to the target DNA sequence are added. These primers bind to the

specific regions of the DNA template.

• Extension: DNA polymerase enzyme adds nucleotides

to the primers, synthesizing new DNA strands that are

complementary to the template DNA.

• Amplification: The denaturation, annealing, and

extension steps are repeated multiple times in a thermal cycler

machine, resulting in the exponential amplification of the target

DNA sequence.

• Detection: The amplified DNA can be visualized using

various methods, such as gel electrophoresis or fluorescent

probes, to confirm the presence of the target DNA sequence.

Challenges and Considerations

Pediatric genetic testing raises a range of ethical issues that need to be carefully considered. The use of rapid genome-wide sequencing (rGWS) in critically ill newborns and children presents new ethical challenges, including issues related to clinical utility, medical uncertainty, impact on family, data security, informed consent, and resource allocation [42].

Ethical challenges in genetic testing for children include:

• Balancing the benefits and risks of genetic testing in

childhood, considering the challenges posed by mainstreaming

genomics and advancements in laboratory technology and

bioinformatics.

• Dealing with the generation of variants of uncertain

significance and unexpected findings during genetic testing.

• Supporting colleagues during the process of

“mainstreaming” genetic testing, as genetics specialists may need

to provide guidance and assistance.

• Carefully considering proposals for genomic screening

of healthy children before implementation, as the ethical

implications need to be weighed.

• Ensuring that the primary goal of genetic testing in

children is to benefit the child and not solely to benefit other

family members [42].

Genomic Stories: Case Studies and Applications

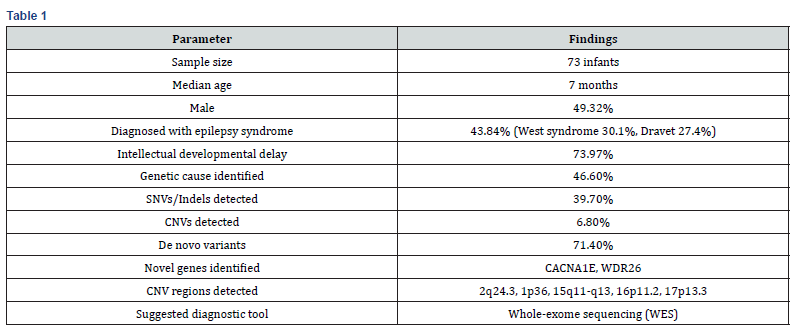

Zhou et al. (2021) studied a group of 73 babies with earlyonset epilepsies (EEs), 49.32% of whom were male and whose median age was 7 months. West syndrome (30.1%) and Dravet syndrome (27.4%) were the most common epilepsy syndromes, accounting for 43.84% of cases. In 73.97% of patients, intellectual developmental delay was noted. 46.6% of the group had pathogenic or possibly pathogenic variants, according to genetic analysis; 39.7% had insertions-deletions (Indels) or single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), and 6.8% had copy number variants (CNVs). The majority of variations that caused disease (71.4%) happened from scratch. The primary etiological factors were variations in ion channel-encoding genes, and two new genes linked to the disease- CACNA1E and WDR26-were discovered. Array comparative genomic hybridization was used to confirm five CNV deletions (2q24.3, 1p36, 15q11-q13, 16p11.2, and 17p13.3) [43]. Another case study was done of a 10-year-old boy who showed the sign of syncope, decreased ejection fraction and dilated cardiomyopathy. (Fung et. Al.,2024). A history of atrial septal defect (ASD) and mild cardiac dilatation at age two was found by retrospective assessment; however, at that time, no genetic evaluation had been carried out. A unique multi-exon loss in the NEXN gene, linked to DCM, was later discovered by thorough genetic testing. This genetic diagnosis had a direct impact on therapeutic decisionmaking: a single-chamber implanted cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was inserted to lower the risk of arrhythmia, and medicinal therapy guided by guidelines was started right away. The case study shows how important early genetic testing is in pediatric cardiology for directing treatment interventions, prognosis, family counseling, and continuous monitoring. The necessity of including genetic analysis in the routine examination of pediatric cardiomyopathy is further supported by the possibility that early identification of the genetic etiology could have changed the course of the disease [44] (Table 1).

Future in Paediatric Cardiology Genetics

The future of paediatric cardiology is being redefined by the new innovations. Highly efficient and wellput next generation platforms (NGP) are now capable of delievering whole-exome or whole-genome data. The field of pediatric cardiology genetics is undergoing a revolution due to rapid technical advancements. Deep intronic mutations, epigenetic variations, and structural variants that were previously unreachable can now be found thanks to whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and long-read sequencing technology [45]. Unprecedented insights into heart development at the cellular level are made possible by developments in singlecell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics. To anticipate disease onset, severity, and treatment effects, genetic data is rapidly being combined with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) models [46]. Additionally, early detection of congenital heart disease (CHD) even before birth is expected by non-invasive fetal whole-genome sequencing. These technologies are advancing from research to normal clinical practice as costs come down and computer power increases, bringing in a new era of thorough and early genetic identification. Better risk assessment, individualized surveillance, and proactive management techniques for juvenile cardiac patients will be made possible by this shift.

Genetic Testing’s Integration with Pediatric Precision Medicine

Clinical care is being altered by the use of genetic testing into pediatric precision cardiology. Finding genetic alterations improves diagnosis and enables treatment targeting and patientspecific prognostication. For example, the use of customized medical therapy and the timing of interventions such as implanted cardioverter-defibrillators are guided by the genetic analysis used to differentiate between sarcomeric and non-sarcomeric forms of cardiomyopathy [47]. For family members who are at risk, cascade genetic testing allows for early identification and preventive care. Pharmaco-genomic methods are also becoming more popular; for example, knowing ion channel mutations can help choose antiarrhythmic medications for channelopathies. The care paradigm is increasingly reliant on multidisciplinary genetic heart teams, which bring together geneticists, cardiologists, and genetic counsellors [48]. Crucially, automated decision-support systems will be made possible by the real-time integration of genetic data into electronic health records (EHRs), simplifying precision medicine techniques. Such integrative approaches will guarantee that each juvenile cardiac patient receives care that is as distinct as their genetic makeup in the future. Pediatric cardiology could benefit greatly from genetic therapy. For hereditary cardiac disorders such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy-related cardiomyopathy, gene replacement, gene editing (CRISPR-Cas9), and antisense oligonucleotide therapy are entering early clinical trials [49]. The goal of cutting-edge techniques like in vivo genome editing is to directly fix harmful variations in cardiac tissues. Studies for heart regeneration are also presented by gene editing in conjunction with stem-cell-based treatments [49]. But longterm safety issues, delivery difficulties, and ethical issues need to be carefully handled. As our knowledge grows, these treatments could eventually change the paradigm in pediatric cardiology from managing diseases to actually curing them.

Conclusion

Today, the genetic revolution in pediatric cardiology is actively changing clinical practice rather than being an abstract concept. The use of genetics is significantly changing the treatment of pediatric heart disorders, from improving early diagnosis through next-generation sequencing to directing daily therapy choices and opening up new avenues for gene-targeted medicines. Advances in technology like artificial intelligence, whole-genome sequencing, and precision medicine frameworks are setting the stage for proactive, individualized care that is based on each child’s own genetic makeup. Additionally, the development of stem cell and gene editing technology portends the intriguing prospect of not just treating but possibly curing inherited heart disorders. However, there are still obstacles to overcome, including as cost, accessibility, ethical concerns, and the requirement for thorough long-term research. Multidisciplinary cooperation, ongoing innovation, and a strong dedication to patient-centered care will be essential as we proceed.

Pediatric cardiology can bring in a new era when genetics gives us the ability to permanently alter the course of young lives by seizing these chances.

References

- Rachel Hart, Angus John Clarke, Alison Hall (2022) 309 Genetic testing in childhood: ethics in practice. BMJ 107(2).

- Lauren Chad, Diana Cagliero, Robin Z Hayeems, Linh Ly, Anna Szuto (2022) Rapid Genetic Testing in Pediatric and Neonatal Critical Care: A Scoping Review of Emerging Ethical Issues. Hospital pediatrics 12(10): e347-e359.

- Yael Ben-Haim, Ajanthah Sangaralingam, Alan M Pittman, D Johnson, Sam Mohiddin, et al. (2023) Whole genome sequencing in the 100,000 Genomes project identifies a RYR2 variant associating with dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden unexpected death in the young. Europace 25(Supplement_1).

- Francesca Girolami, Maria Iascone, Laura Pezzoli, Silvia Passantino, Giuseppe Limongelli, et al. (2022) [Clinical pathway on pediatric cardiomyopathies: a genetic testing strategy proposed by the Italian Society of Pediatric Cardiology]. Giornale italiano di cardiologia 23(7): 505-515.

- Robert Lesurf, Abdelrahman Said, Oyediran Akinrinade, Jeroen Breckpot, Kathleen Delfosse, et al. (2020). Whole genome sequencing delineates regulatory and novel genic variants in childhood cardiomyopathy. medRxiv.

- Jay D Fisher, Robert J Bechtel, Korrina N Siddiqui, David G Nelson, Ahmad Nezam (2019) Clinical spectrum of previously undiagnosed pediatric cardiac disease. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 37(5): 933-936.

- A Elhyka, J Fumanelli, Giovanni Di Salvo, Sabino Iliceto, Loira Leoni (2022) P170 value of electrocardiographic screening for early detection of arrhythmic and malignant heart disease in children. European Heart Journal Supplements 24(Supplement_C).

- Luciane Piazza, Angelo Micheletti, Diana Negura, Carmelo Arcidiacono, Antonio Saracino, et al. (2012) Early Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease: When and How to Treat. Springer 569-576.

- Vanessa Costa, Marilia Loureiro (2021) Paediatric hypertension: The importance of prevention and early diagnosis. Interventional Cardiology 13(1): 216.

- Daniel Esau, Beth L Abramson (2022) Approach to risk stratification of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Canadian Family Physician 68(9): 654-660.

- Francesca Girolami, Maria Iascone, Laura Pezzoli, Silvia Passantino, Giuseppe Limongelli, et al. [Clinical pathway on pediatric cardiomyopathies: a genetic testing strategy proposed by the Italian Society of Pediatric Cardiology]. Giornale italiano di cardiologia 23(7): 505-515.

- Dana B Gal, Ana Morales, Susan Rojahn, Tom Callis, John Garcia, et al. (2021) Comprehensive Genetic Testing for Pediatric Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Reveals Clinical Management Opportunities and Syndromic Conditions. Pediatric Cardiology 43: 616-623.

- Andrew P Landstrom, Jeffrey J Kim, Bruce D Gelb, Benjamin M Helm, Prince J Kannankeril.et al, (2021) Genetic Testing for Heritable Cardiovascular Diseases in Pediatric Patients: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Genom Precis Med 14(5): e000086.

- Nicoleta-Monica Popa-Fotea, Cosmin Cojocaru, Alexandru Scafa-Udriste, Miruna Mihaela Micheu, et al. (2020) The Multifaced Perspectives of Genetic Testing in Pediatric Cardiomyopathies and Channelopathies. Journal of Clinical Medicine 9(7): 2111.

- Shuenn-Nan Chiu, Jyh-Ming Jimmy Juang, Wei-Chieh Tseng, Wen-Pin Chen, Ni-Chung Lee, et al. (2021) Impact of genetic tests on survivors of pediatric sudden cardiac arrest. Archives of Disease in Childhood 107(1): 41-46.

- Agnish Ganguly, Pinku Halder, Upamanyu Pal, Sujay Ghosh (2023) An insight into genetics of congenital heart defects associated with Down syndrome. Medical research archives 11(4).

- Nunzia Mollo, Roberta Scognamiglio, Anna Conti, Simona Paladino, Lucio Nitsch, et al. (2023) Genetics and Molecular Basis of Congenital Heart Defects in Down Syndrome: Role of Extracellular Matrix Regulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24(3): 2918.

- Leslye Venegas-Zamora, Francisco Bravo-Acuña, Francisco Sigcho, Wileidy Gomez, José Bustamante-Salazar, et al. (2022) New Molecular and Organelle Alterations Linked to Down Syndrome Heart Disease. Frontiers in Genetics 12: 792231.

- Carmela Rita Balistreri, Claudia Leonarda Ammoscato, Letizia Scola, Tiziana Fragapane, Rosa Maria Giarratana, et al. (2020) Susceptibility to Heart Defects in Down Syndrome Is Associated with Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in HAS 21 Interferon Receptor Cluster and VEGFA Genes. Genes 11(12): 1428.

- Sultan Ozcelik, Osman Baspinar, Gülper Nacarkahya (2022) Investigation of DEL22 Frequency with Fluorescent in Situ Hybridization Method in Children with Conotruncal Heart Anomaly. European journal of therapeutics 28(3): 242-246.

- Carolina Putotto, Flaminia Pugnaloni, Marta Unolt, Stella Maiolo, Matteo Trezzi, et al. (2022) 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome: Impact of Genetics in the Treatment of Conotruncal Heart Defects. Children (Basel) 9(6): 772.

- Manisha Agarwal, Vivek Kumar, Aradhana Dwivedi (2022) Diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in children with congenital heart diseases and facial dysmorphisms. Medical journal Armed Forces India79(Suppl 1): S196-S201.

- Marta Unolt, Giulio Calcagni, Carolina Putotto, Paolo Versacci, Maria Cristina Digilio, et al. (2022) congenital heart disease and cardiovascular abnormalities associated with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Academic press 78-100.

- Elizabeth Goldmuntz (2020) 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and congenital heart disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C-seminars in Medical Genetics 184(1): 64-72.

- Divya Kumari, Deepti Chaudhary, Inusha Panigrahi, Manoj Kumar Rohit (2020) Genetic Defects in Children with Cardiac Anomalies/Malformations: Noonan and CFC Syndromes. Journal of pediatric genetics 12(1): 86-89.

- RD Bagnall, ES Singer, J Wacker, N Nowak, J Ingles, et al. (2022) Genetic Basis of Childhood Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 15(6): e003686.

- I Novgorodova (2023) Possibilities of using micronucleus analysis to detect gene mutations in animals. Agrarnaâ nauka 23-29.

- L Palanikumar, N Panneerselvam (2011) Micronuclei assay: A potential biomonitoring protocol in occupational exposure studies. Russian Journal of Genetics 47(9): 1033-1038.

- Anne Vral, Michael Fenech, Hubert Thierens (2011) The micronucleus assay as a biological dosimeter of in vivo ionising radiation exposure. Mutagenesis 26(1): 11-17.

- RD Bagnall, ES Singer, J Wacker, N Nowak, J Ingles, et al. (2022) Genetic Basis of Childhood Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 15(6): e003686.

- Richard D Bagnall, Emma S Singer, Julie Wacker, N Nowak, Jodie Ingles, et al. (2022). Genetic Basis of Childhood Cardiomyopathy. Circ Genom Precis Med 15(6): e003686.

- Yan Wang, Bo Han, Youfei Fan, Yingchun Yi, Jianli Lv, et al. (2021). Next-Generation Sequencing Screening Reveals Novel Genetic Variants for Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Pediatric Chinese Patients. Pediatr Cardiol 43(1): 110-120.

- V Michalová, M Galdíková, Beáta Holečková, S Koleničová, Viera Schwarzbacherová (2020) Micronucleus Assay in Environmental Biomonitoring. Sciendo 64(2): 20-28.

- Robert Lesurf, Abdelrahman Said, Oyediran Akinrinade, Jeroen Breckpot, Kathleen Delfosse, et al. (2022) Whole genome sequencing delineates regulatory, copy number, and cryptic splice variants in early onset cardiomyopathy. npj Genomic Medicine 7(1):18.

- Robert Lesurf, Abdelrahman Fekry, Abdelrahman Said, Oyediran Akinrinade, Jeroen Breckpot, et al. (2022) Whole genome sequencing delineates regulatory, copy number, and cryptic splice variants in early onset cardiomyopathy. npj Genomic Medicine 7(1): 18.

- Yael Ben-Haim, Ajanthah Sangaralingam, Alan M Pittman, D Johnson, Sam Mohiddin, et al. (2023) Whole genome sequencing in the 100,000 Genomes project identifies a RYR2 variant associating with dilated cardiomyopathy and sudden unexpected death in the young. Europace 25 (Supplement_1).

- Francesca Girolami, Maria Iascone, Laura Pezzoli, Silvia Passantino, Giuseppe Limongelli, et al. (2022) [Clinical pathway on pediatric cardiomyopathies: a genetic testing strategy proposed by the Italian Society of Pediatric Cardiology]. Giornale italiano di cardiologia 23(7): 505-515.

- Robert Lesurf, Abdelrahman Said, Oyediran Akinrinade, Jeroen Breckpot, Kathleen Delfosse, et al. (2020) Whole genome sequencing delineates regulatory and novel genic variants in childhood cardiomyopathy. medRxiv.

- Simpson KE, Storch GA, Lee CK, Ward KE, Danon S, et al. (2016) High Frequency of Detection by PCR of Viral Nucleic Acid in The Blood of Infants Presenting with Clinical Myocarditis. Pediatric Cardiology 37(2): 399-404.

- Calabrese F, Rigo E, Milanesi O, Boffa G, Angelini A, et al. (2002) Molecular diagnosis of myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy in children: clinicopathologic features and prognostic implications. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology 11(4): 212-221.

- Rachel Hart, Angus Clarke, Alison Hall (2022) 309 Genetic testing in childhood: ethics in practice. Archives of Disease in childwood 107(2).

- Sun D, Liu Y, Cai W, Ma J, Ni K, et al. (2021) Detection of Disease-Causing SNVs/Indels and CNVs in Single Test Based on Whole Exome Sequencing: A Retrospective Case Study in Epileptic Encephalopathies. Front Pediatr 9: 635703.

- Fung EC, Collins R, Dellefave-Castillo L, et al. (2024) The critical role of clinical genetic testing in pediatric dilated cardiomyopathy: A case report. Genetics in Medicine Open.

- Manickam K, McClain MR, Demmer LA, Biswas S, Kearney HM, et al. (2021) Exome and genome sequencing for pediatric patients with congenital anomalies or intellectual disability: an evidence-based clinical guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med 23(11): 2029-2037.

- Topol EJ (2019) High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med 25(1): 44-56.

- Ingles J, Goldstein J, Thaxton C, Caleshu C, Corty EW, et al. (2019) Evaluating the clinical validity of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy genes. Circ Genom Precis Med 12(2): e002460.

- Palmen R, Walton M, Wagner J (2024) Pediatric flecainide pharmacogenomics: a roadmap to delivering precision-based care to pediatric arrhythmias. Frontiers in Pharmacology 15:1477485.

- Nelson CE, Hakim CH, Ousterout DG, Thakore PI, Moreb EA, et al. (2021) In vivo genome editing improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science 362(6410): 403-407.