Abstract

Rare diseases affect millions in India, yet remain largely neglected in health policy, infrastructure, and medical practice. As a practicing genetic counselor, I witness daily the burden rare diseases place not only on patients but also on caregivers and clinicians navigating diagnostic uncertainties, limited treatment options, and deep social stigma. This mini commentary reflects on the ethical, clinical, and emotional challenges of rare diseases in India, highlighting the need to include rare conditions in national healthcare planning. By sharing lived experiences, systemic gaps, and ethical reflections, the article argues that rare diseases are not rare in impact-and must no longer be rare in India’s medical conscience.

Keywords:Rare Diseases; Genetic Counseling; Health Ethics; Psychosocial Burden; National Policy

What is Known About this Topic

Rare diseases affect millions in India, yet families often face delayed diagnoses, limited access to care, and social stigma. Genetic counselors play a critical but under-recognized role in guiding these families.

What this Paper Adds to the Topic

This commentary highlights the ethical and emotional realities of rare disease care in India and calls for national policy inclusion, stronger genetic counseling services, and community advocacy to ensure equity and dignity for affected families.

Main Content

What is “Rare” in India?

Rare diseases are often defined by prevalence affecting fewer than 1 in 2,000 people in the Europe but in India, where such a unified definition is missing, rarity takes on broader, more complex meanings [1]. It can mean being undiagnosed for years, being misunderstood by clinicians, or being stigmatized by society. The National Policy for Rare Diseases (2021) identifies about 450 diseases, though over 7,000 rare conditions exist globally. While individual diseases are uncommon, collectively they affect more than 70 million Indians [2]. In my practice, I frequently meet families from across India-rural Karnataka, Maharashtra to urban Hyderabad who have spent years looking for answers. Their children often suffer from progressive neurological disorders, rare skeletal dysplasias, or inherited metabolic errors. They do not consider their child’s condition “rare.” For them, it is a constant, consuming reality. The term “rare” becomes a misnomer when lived experience is anything but rare.

The Long Road to a Diagnosis

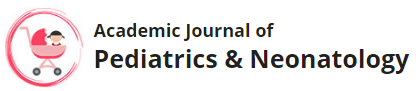

One of the most painful truths in rare disease care is the “diagnostic odyssey.” This refers to the long, uncertain, and often fragmented journey families undertake to find the correct diagnosis. The average time to diagnose a rare disease globally is 5-7 years, and in India, this journey is often longer due to limited awareness among clinicians, lack of diagnostic labs, and geographic inequities in access [3,4] (Figure 1). Families are often passed between neurologists, pediatricians, and other specialties, each treating symptoms in isolation. In many government hospitals, clinicians may never have heard of rare diseases like Canavan disease, CDKL5 encephalopathy, or Pompe disease. Genetic tests such as exome sequencing or chromosomal microarrays, though available in India, are costly and largely concentrated in metropolitan diagnostic centers. This often leads to late diagnosis or complete diagnostic failure [5]. A diagnosis is more than a medical label-it is often the first step toward emotional acceptance, planning for care, and accessing potential therapies. Denial of timely diagnosis is an ethical issue, affecting the principle of beneficence and the right to know one’s medical condition.

The Emotional and Social Weight

Rare diseases do not affect just the body, they affect the mind, the family, and the social environment. I have met parents who were blamed for “giving birth to a cursed child,” couples who were ostracized by extended family, and mothers who contemplated suicide because they felt responsible for their child’s illness. In Indian society, disability and genetic disorders still carry moral judgment. Women often bear the brunt of this stigma, with inlaws and communities questioning their worth or purity. Families with affected children experience social withdrawal, school discrimination, and emotional burnout [6]. Many parents stop working, siblings are neglected, and marriages break down under the weight of caregiving (Figure 2). There is also internalized stigma. Many families choose not to talk about the diagnosis, fearing judgment. Counseling becomes not only about providing genetic information but offering emotional first aid. Ethical genetic counseling must include empathy, cultural sensitivity, and long-term psychosocial support, which remains largely missing from our healthcare system.

Hope vs. Reality in Treatments

Treatment options exist for some rare diseases such as enzyme replacement therapies, gene therapy, or small molecule drugs but they are mostly out of reach for ordinary Indian families. Treatments like Zolgensma (for Spinal Muscular Atrophy) cost upwards of ₹15 crore. The ethical dilemma this creates is profound: should life-saving treatments be available only to those who can pay or gain public sympathy via crowdfunding? India’s National Policy for Rare Diseases created three groups of diseases based on treatment availability and funding need. However, the scheme is limited in scope. It applies only to certain conditions and only for government-empanelled hospitals. Most patients are left outside this net. Even when treatments exist, import processes, lack of trained specialists, and fragmented care models delay or deny therapy. Equity in healthcare is an ethical right. No child should be denied treatment because their disease is rare or their family poor. Public-private partnerships, expanded health insurance, and compulsory price regulation are needed to reduce this gap between science and access.

Navigating Reproductive Decisions

Reproductive choices in families affected by rare diseases are often difficult. As counselors, we must ensure non-directiveness and informed consent. But in many cases, socio-cultural pressures, gender hierarchies, and incomplete information skew decision-making. For instance, a couple may seek prenatal testing in a subsequent pregnancy after losing a child to a genetic disorder. Explaining recurrence risks (e.g., 25% in autosomal recessive inheritance) is crucial, but families may lack the scientific background to fully grasp this. They may be emotionally overwhelmed or culturally influenced to avoid termination. It is ethically essential that counseling does not coerce decisions but empowers families with accurate, culturally sensitive, and compassionate information. In rural settings, this is especially challenging due to language barriers, low health literacy, and the unavailability of follow-up care.

The Role of Support Groups

Despite the challenges, a growing force of hope is visible in rare disease support groups. Parents have organized into advocacy networks like BharathMD Foundation, CureSMA-India, LSDSS,CDKL5 South Asia, LAMA2-CMD and the Organization for Rare Diseases India (ORDI). These groups share medical information, connect families with doctors, push for policy change, and offer critical emotional support [7]. They play a key ethical role in restoring dignity and agency to families. They challenge the medical hierarchy by centering patient voices. As a counselor, I’ve found that linking families to such communities enhances acceptance, reduces isolation, and creates solidarity. Ethics in healthcare is not only about professional codes; it is also about building humane networks of care and trust.

The Policy Landscape: Progress but Not Enough

India’s first National Policy for Rare Diseases (2017) was withdrawn and revised in 2021, reflecting ongoing tension between vision and feasibility. The current policy emphasizes research, newborn screening, treatment support for select diseases, and the creation of a digital crowdfunding platform. Yet implementation is weak. There is no centralized rare disease registry. Newborn screening is not standardized across states. Genetic services are concentrated in cities, leaving large populations without access. The ethical principle of justice is compromised when policy promises are not translated into reality. India must include rare diseases in national health insurance schemes, such as Ayushman Bharat. Rare disease diagnostics should be integrated into maternal and child health programs, and state-level referral networks should be created [8]. Moreover, India must invest in genetic counselor training programs and recognize this profession under national health missions. Ethics begins with inclusion.

Genetic Counseling: Beyond Science, Toward Humanity

As a practicing genetic counselor, I have often sat across from parents whose child has just been diagnosed with a life-limiting condition. In that moment, I am not just a healthcare provider-I am a witness to grief, guilt, confusion, and hope. My job goes beyond interpreting genetic variants. I must explain recurrence risk, answer “why us?”, and support them through loss or decisions about future pregnancies. India needs more trained genetic counselors-not only in tertiary care hospitals, but in district health centers, special education schools, and reproductive clinics. Counseling should not be a luxury service [9]. It is an ethical necessity that brings clarity, compassion, and informed choice to families navigating rare diseases. The role and scope of genetic counselors in India is expanding, but public awareness and formal inclusion into clinical care remain limited. A recent article emphasized the urgent need to integrate genetic counseling into routine healthcare and reproductive services in India, highlighting gaps in professional training, policy recognition, and institutional support [10]. Without systemic investment in this profession, the potential of personalized, ethical care for rare disease families remains underutilized.

Ethical Questions That Cannot Be Ignored

Rare diseases raise fundamental ethical questions:

a) Should cost determine access to treatment?

b) Who decides which diseases get funding?

c) How do we ensure dignity for disabled children in a

society still uncomfortable with difference?

d) What is the role of the state in preventing, screening, and

treating these conditions?

We must approach rare diseases not just as medical phenomena, but as reflections of what kind of society we wish to build. A just society includes its most vulnerable members in its healthcare imagination.

A Call for Inclusion

The core message of this article is simple yet urgent: India must formally and ethically include rare diseases in its national health priorities. These are not fringe conditions-they affect millions and strain families emotionally, financially, and socially. Health equity demands that we do not leave behind those with the rarest needs. We need a national rare disease mission-with dedicated funding, ethical oversight, public awareness campaigns, and systemic capacity building. India cannot wait for perfect solutions. It must begin with practical, scalable steps rooted in compassion, ethics, and scientific integrity.

Conclusion

“How rare is rare?” is no longer a rhetorical question. It is a measure of the ethical resilience of our healthcare system and our societal commitment to equitable care. As a genetic counselor, I witness firsthand the lived realities of individuals and families navigating rare diseases-facing delayed diagnoses, limited treatment options, and pervasive psychosocial burdens. Their struggles are not isolated; their rights are fundamental. It is time to move beyond viewing rare diseases as exceptions. We must recognize them as integral to the broader pursuit of inclusive, patient-centered healthcare. By embedding rare diseases within national health priorities, expanding access to genetic counseling, and addressing systemic gaps in diagnosis and care, we can uphold the dignity and agency of every affected individual. No condition should be too rare to matter. No child, family, or citizen should be left behind.

References

- (2023) Orphanet. About Rare Diseases.

- (2021) Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Policy for Rare Diseases. Government of India.

- Singh J, Verma IC, Gupta N (2023) Rare diseases in India: Overcoming challenges with collaborative frameworks. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 90(4): 320-326.

- Groft SC, De la Paz MP (2010) Rare diseases -avoiding misperceptions and establishing realities. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 9(12): 895-896.

- Ravichandran R, Dhamija RK, Goyal V (2021) Challenges and current landscape of genetic testing in India. Neurology India 69(2): 245-252.

- (2017) Eurordis. The Voice of 12,000 Patients: Experiences and Expectations of Rare Disease Patients on Diagnosis and Care in Europe.

- (2022) Organization for Rare Diseases India. Annual Status Report.

- Baru R, Acharya A (2022) Equity and access in Indian healthcare: The case of orphan drugs and rare diseases. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 7(3): 205-210.

- Skirton H, Cordier C, Ingvoldstad C, Taris N, Benjamin C, et al. (2015) The role of genetic counsellors: a systematic review of research evidence. European Journal of Human Genetics 23(4): 452-458.

- Aman N (2025) The role, importance of genetic counsellors and the awareness of genetic counselling in Indian scenario. Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences 18(1): 45-47.