Abstract

Isolated epispadias is a rare congenital urological anomaly that can be easily missed, particularly when associated with a concealed penis and intact prepuce. We report the case of a 4-year-old boy who presented with continuous urinary dribbling and a hidden penile shaft. The condition was first noticed during a failed circumcision attempt, but no diagnosis was made until further evaluation at a tertiary care center. Examination revealed a dorsally located urethral meatus and unretractable foreskin, consistent with isolated epispadias. Investigations showed mild anemia and pyuria, with normal renal function and imaging. Surgical correction was performed using the Inverted Preputial Glanuloplasty and Meatoplasty (IPGAM) technique, along with corporoplasty and tuboplasty. The procedure was successful, with no complications. This case highlights the importance of early recognition of atypical penile anatomy, especially during circumcision, and the need for improved paediatric surgical services and awareness in resource-limited settings to prevent diagnostic delays and functional impairment.

Key Clinical Message:Isolated epispadias can remain hidden behind an intact foreskin, making early diagnosis especially difficult-often only discovered during circumcision attempts. This case highlights the importance of careful genital examination in infants and the need for greater awareness among healthcare providers. With timely recognition and a tailored surgical approach like IPGAM, even children in resource-limited settings can achieve excellent functional and emotional outcomes.

Keywords: Isolated Epispadias; Buried Penis; Concealed Epispadias; Paediatric Urology, Circumcision Complication; IPGAM Technique; Urethral Reconstruction; Urinary Incontinence

Abbreviations: BEEC: Bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex; GE: Glanular epispadias; PPE: Penopubic epispadias; IME: Isolated male epispadias; PE: Penile epispadias; QHAMC: Qazi Hussain Ahmad Medical Complex; IPGAM: Inverted Preputial Glanuloplasty and Meatoplasty; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; BEEC: Bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex

Introduction

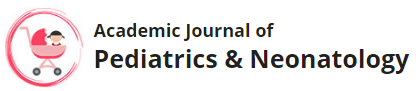

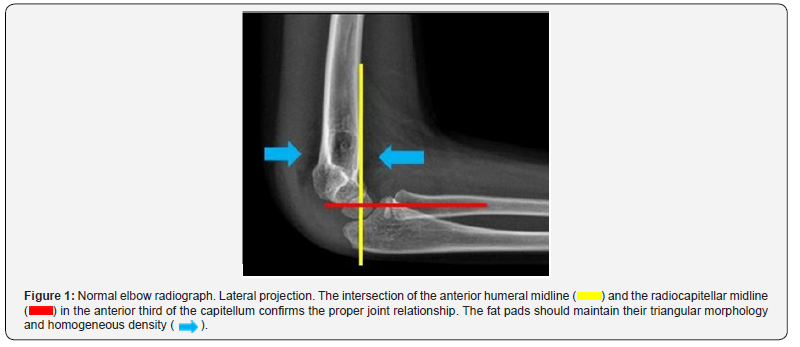

Elbow trauma in children is the second leading cause of emergency department visits, with supracondylar fracture being the most common diagnosis, affecting between 5 and 7 years of age [1]. Correct identification, classification and timely intervention will reduce morbidity, as consolidation in the immature skeleton of children occurs quickly. They usually affect the area most proximally to metaphysis, i.e., the hypertrophic, vascularized and provisionally calcified area with a high risk of neurovascular complications [1,2]. Clinical suspicion begins with a history of trauma in forced extension (more than 97% of cases), while the flexion type is much less common; as well as data on physical examination such as functional limitation, exclusion of the limb and edema [1,3]. The diagnosis supported by diagnostic images is made by means of elbow radiography, which consists of anteroposterior and lateral projections, the latter being the most important and relevant in the diagnosis (Figure 1) [4]. For the imaging findings we first familiarized ourselves with the identification of the ossification nuclei, facilitated by the CRITOE menometechnics (Figure 2), (Capitellum, radius, internal epicondyle, trochlea, olecranon, external epicondyle) with their age of appearance 1-3-5-7-9-11 years, respectively [5]. Findings associated with trauma include the fat pad sign, which is defined as bulging and/or effacement of the fat pad, joint effusion, loss of joint relationship and most importantly the fracture line for subsequent Gartland classification. Complementary tomography is relieved for cases with negative radiographs and clinical suspicion as well as for surgical planning due to complexity in some cases [1,6].

Results

A deliberate search was carried out in the PACS for elbow X-rays with supracondylar fracture performed on patients of any gender aged 2 to 18 years between January 2024 and February 2025, obtaining 150 patients, where men with an age range between 6 and 10 years (mean 7 years) and the left elbow (70%) were the most affected, they attended the emergency room 4 hours after the trauma due to persistent pain, with a maximum of 12 hours. The Gartland fracture Type Ia was the most common fracture, followed by type III. Conservative management was the most prevalent.

Discussion

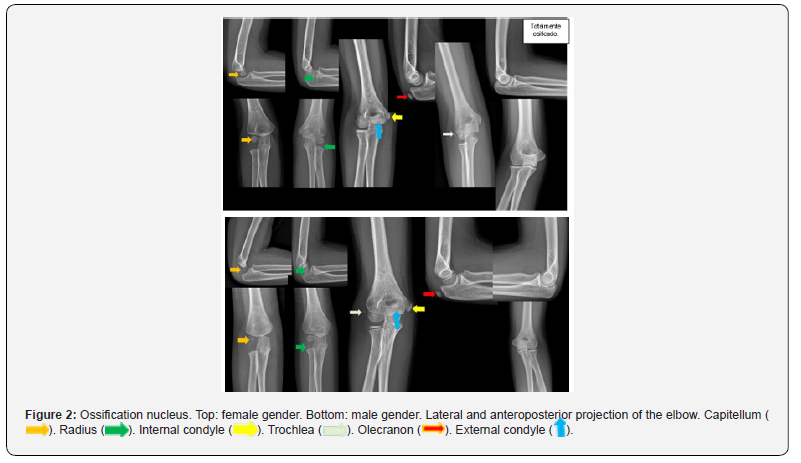

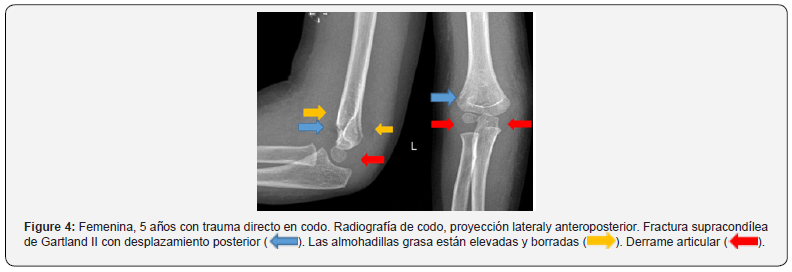

Upper extremity injuries are estimated to account for 65% of all fractures in children. The modified Gartland classification system for supracondylar fractures includes non-displaced type I, where the fracture line or fat pad sign is seen on the lateral radiograph (Figure 3) [5-8]. Gartland I supracondylar fracture. Top: Female, 2 years old. Bottom: Male, 7 years old, initial elbow radiograph and 20-day follow-up. Lateral and anteroposterior elbow radiograph. Incomplete fracture at the posterior humeral border ( ) associated with joint effusion (

) associated with joint effusion ( ), widening and effacement of the posterior fat pad (

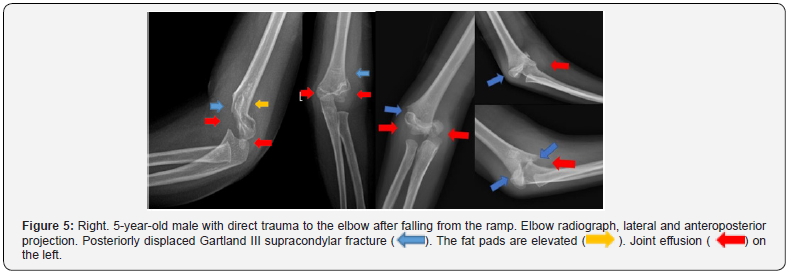

), widening and effacement of the posterior fat pad ( ). Type II shows moderate displacement, where the posterior cortex remains in continuity (IIa without rotation, IIb rotation). (Figure 4) [2,3,8]. Type III shows complete displacement (Figure 5) and type IV is unstable in flexion/extension (intraoperative evaluation). Elbow radiograph, lateral and anteroposterior projection. Posteriorly displaced Gartland III supracondylar fracture (

). Type II shows moderate displacement, where the posterior cortex remains in continuity (IIa without rotation, IIb rotation). (Figure 4) [2,3,8]. Type III shows complete displacement (Figure 5) and type IV is unstable in flexion/extension (intraoperative evaluation). Elbow radiograph, lateral and anteroposterior projection. Posteriorly displaced Gartland III supracondylar fracture ( ). The fat pads are elevated (

). The fat pads are elevated ( ). Joint effusion (

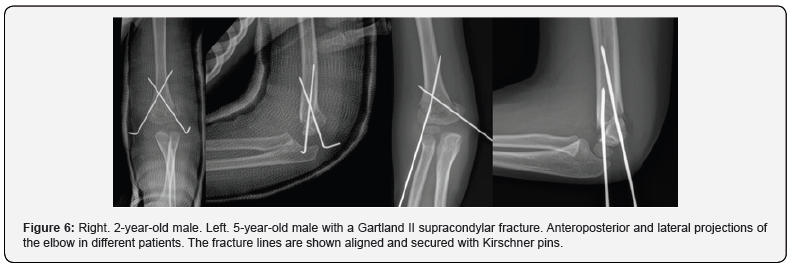

). Joint effusion ( ) on the left. Early correction prevents valgus deformity of the ulna as well as biomechanical alterations of the elbow. Management includes, for the most part, conservative (closed reduction) and surgical, which includes reduction and fixation with osteosynthesis material (Figure 6) [4].

) on the left. Early correction prevents valgus deformity of the ulna as well as biomechanical alterations of the elbow. Management includes, for the most part, conservative (closed reduction) and surgical, which includes reduction and fixation with osteosynthesis material (Figure 6) [4].

Conclusion

Correct identification and classification of the supracondylar fracture allowed for timely intervention and short follow-up without evidence of deformity or refracture.

References

- Zaidman M, Eidelman M, Abu-dalu K (2023) Pediatric Supracondylar Fracture of the Humerus with Sideward Displacement 12(3): 107-118.

- Duffy S, Flannery O, Gelfer Y, Monsell F (2021) Overview of the contemporary management of supracondylar humeral fractures in children. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 31(5): 871-881.

- Dalrymple J (2024) Doctors in Training Pediatric supracondylar fractures: assessment and management 85(2): 1-7.

- Poggiali P, Carlos F, Nogueira S, Paula M, Nogueira DM (2022) Management of Supracondylar Humeral Fracture in Children Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo) 57(1): 23-32.

- Shenoy PM, Islam A, Puri R (2020) Current Management of Pediatric Supracondylar Fractures of the Humerus 12(5): e8137.

- Ihsan M, Dias Y, Saleh MR, Sakti M, Asri M, et al. (2020) International Journal of Surgery Open Analysis of radiological alignment and functional outcomes of pediatric patients after surgery with displaced supracondylar humerus fracture: A cross-sectional study. Int J Surg Open 24: 136-142.

- Azzam W, Catagni MA, Ayoub MA, El-sayed M, Thabet AM (2020) Early correction of malunited supracondylar humerus fractures in young children. Injury 51(11): 2574-2580.

- B Kappelhof, BL Roorda, MA Poppelaars, B The, D Eygendaal, et al. (2022) Occult Fractures in Children with a Radiographic Fat Pad Sign of the Elbow: A Meta-Analysis of 10 Published Studies. JBJS Reviews 10(10).