Abstract

Background: Malnutrition remains a critical public health issue in Tanzania, particularly among children under five, contributing to high morbidity and mortality rates. This study investigates the prevalence and risk factors associated with malnutrition among under-five children at Temeke Regional Referral Hospital (TRRH) in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and compares nutritional status between preterm and full-term children.

Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted from February to March 2025, at TRRH, involving 83 children under five years. Data was collected using semi-structured questionnaires and anthropometric measurements (weight, height, mid-upper arm circumference). Prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight was assessed using WHO Child Growth Standards (2006). Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests (p < 0.05) were analyzed via SPSS version 20.0 to identify risk factors and compare preterm and full-term children.

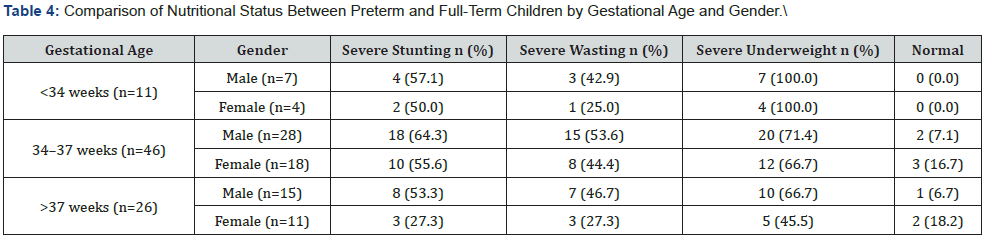

Results: Among 83 children, 63.9% were severely underweight, 54.2% severely stunted, and 50.6% severely wasted. Key risk factors included lack of exclusive breastfeeding (33.7%, p = 0.012), poor maternal nutrition knowledge (27.7%, p = 0.045), and comorbidities (20.5%, p = 0.210). Preterm children (<37 weeks gestation) had higher rates of stunting, wasting, and underweight than full-term peers (p < 0.05). Males were more affected than females, potentially due to higher metabolic demands.

Conclusion: Malnutrition is highly prevalent at TRRH, driven by inadequate breastfeeding, low maternal education, and health challenges. Preterm children and males are particularly vulnerable. Interventions should prioritize maternal education, exclusive breastfeeding promotion, and specialized preterm care to reduce malnutrition.

Keywords:Exclusive breastfeeding, Malnutrition; Preterm infants; Stunting, Tanzania; Temeke Regional Referral Hospital; Under-five children; Underweight; Wasting

Abbreviations: TRRH: Temeke Regional Referral Hospital; NMNAP: National Multisectoral Nutrition Action Plan; MUAC: Mid-Upper Arm Circumference; WHO: World Health Organization; SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; KIUT: Kampala International University in Tanzania

Introduction

Malnutrition among children under five is a critical global health challenge, contributing to 45% of deaths in this age group, with an estimated 45 million cases of wasting and 149 million cases of stunting worldwide [1]. It manifests as stunting (low height-for-age), wasting (low weight-for-height), and underweight (low weight-for-age), driven by poverty, food insecurity, inadequate maternal nutrition, and infectious diseases such as diarrhea and pneumonia [2]. These conditions impair immune function, increase susceptibility to infections, and cause developmental delays, reducing productivity and increasing chronic disease risk in adulthood [3]. Sub-Saharan Africa bears a significant burden, accounting for one-third of global malnutrition cases, with over 204 million affected, primarily due to poverty, illiteracy, large families, and infectious diseases [4]. In East Africa, severe malnutrition is prevalent among hospitalized children, with a 16% prevalence reported at Kilifi Hospital in Kenya and higher rates of edematous malnutrition at Muhimbili National Hospital in Tanzania, with boys more affected than girls [5]. Tanzania ranks third in malnutrition prevalence after Ethiopia and Congo, with 42% of under-five children affected, including 2.7 million malnourished and 600,000 with acute malnutrition [6]. National data indicate 34% stunting, 14% underweight, and 5% wasted, with rural areas like Iringa and Rukwa particularly affected due to poor feeding practices and low maternal education [7,8]. Despite interventions like Tanzania’s National Multisectoral Nutrition Action Plan (NMNAP) 2016–2021, 31.8% of under-five children remain stunted, exceeding the African average of 30.7% [9,8]. Malnutrition is especially severe in rural Tanzania, where limited healthcare access and food insecurity persist [8,9]. Hospital-based studies, such as one reporting over 60% malnutrition prevalence among admitted children in urban Tanzanian hospitals, highlight the issue’s severity in clinical settings [10]. However, most research focuses on national or community surveys, with limited hospital-specific data, particularly for urban facilities like Temeke Regional Referral Hospital (TRRH) in Dar es Salaam [7]. TRRH serves a diverse population, including urban and rural communities, making it an ideal setting to study malnutrition prevalence and risk factors among under five children visiting its pediatric ward. This study addresses the research gap by investigating hospital-based malnutrition at TRRH, examining associated risk factors, and comparing nutritional outcomes between preterm and full-term children. The findings will inform targeted interventions to reduce the malnutrition burden in urban hospital settings and contribute to Tanzania’s ongoing efforts to improve child nutrition.

Methodology

Study Setting

This study was conducted at Temeke Regional Referral Hospital (TRRH) in Temeke District, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, from February 17 to March 7, 2025. Temeke District, one of five administrative districts in Dar es Salaam, spans 150.4 km² with a population of 1,346,674, yielding a density of 8,957 people per km² according to the 2022 Tanzania Population and Housing Census [9]. The district encompasses urban, peri-urban, and rural communities, with TRRH serving as a primary healthcare facility offering specialized pediatric care to approximately 1.3 million residents.

Study Design

A cross-sectional descriptive study with a quantitative approach was employed to assess the prevalence and risk factors of severe malnutrition among children under five years attending the malnutrition clinic at TRRH. This design enabled data collection at a single time point, capturing nutritional status and associated sociodemographic and health-related factors.

Study size determination

The sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula:

where: n is a required sample size,

Z score corresponds to desired confident level=1.96 for 95% confidence,

p is the estimated proportion of an attribute that is present in a population, where by 5.74% of children under five years are underweight. Bagamoyo District Hospital study in 2016.

Selection Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Eligible participants were children under five years of age attending the malnutrion OPD clinic at TRRH with a confirmed or suspected diagnosis of malnutrition, based on clinical assessment or anthropometric measurements.

Exclusion Criteria

Children readmitted during the study period or receiving treatments (e.g., surgery, parenteral nutrition) that could alter nutritional parameters were excluded to ensure data accuracy.

Sampling Technique

A simple random sampling method was utilized. The process involved:

(1) defining the study population as all children under five visiting the malnutrition clinic;

(2) calculating the sample size (n=83);

(3) compiling a sampling frame from a list of eligible children meeting inclusion criteria;

(4) assigning unique numerical identifiers to each child; and

(5) randomly selecting 83 participants using a random number generator.

Data Collection

Data were collected over a three-week period (February 17– March 7, 2025) using validated semi-structured questionnaires administered to caregivers in English or Swahili, adapted from previous malnutrition studies. The questionnaires included open-and closed-ended questions on sociodemographic characteristics, feeding practices, and health history. Anthropometric weight (using calibrated digital scales), height/ length (using meter rulers or infant meters), and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC, using standardized tapes)-were performed by trained healthcare workers following World Health Organization (WHO) protocols. Data was sourced from primary methods (caregiver interviews and anthropometric measurements) and secondary sources (medical records). All tools were pre-tested for reliability in a pilot study involving 10 participants, with adjustments made to ensure clarity and cultural appropriateness.

Data Analysis

Data were cleaned, coded, and entered the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations, were used to summarize sociodemographic characteristics, nutritional status, and risk factors. Chi-square tests assessed differences in nutritional status between preterm and full-term children, with statistical significance defined at p < 0.05. Anthropometric data were converted to Z-scores using WHO growth standards to classify stunting, wasting, and underweight.

Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, prioritizing the welfare and rights of vulnerable participants, including children under five and their caregivers, with ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Kampala International University in Tanzania (KIUT) and permission from Temeke Regional Referral Hospital (TRRH). Informed consent, obtained verbally and in writing in Swahili or English based on caregivers’ preferences, was voluntary, with clear explanations ensuring participants understood their right to withdraw without affecting healthcare access. Non-invasive methods (anthropometric measurements, interviews) and nutritional counselling minimized risks. Confidentiality was ensured through unique identifiers, encrypted data storage, and restricted access, with only de-identified results reported, maintaining integrity and cultural sensitivity under KIUT oversight.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

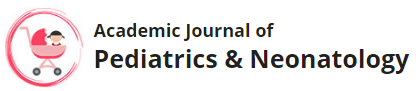

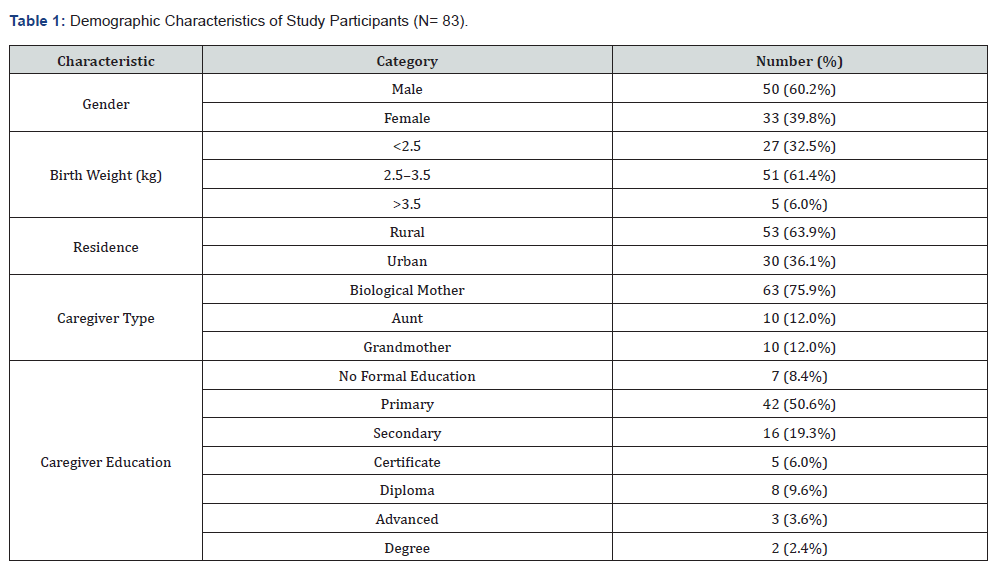

A total of 83 children under five years of age were enrolled in the study. The majority were male (50, 60.2%), with females comprising 33 (39.8%). Most had a birth weight of 2.5–3.5 kg (51, 61.4%), followed by 3.5 kg (5, 6.0%). Participants predominantly resided in rural areas (53, 63.9%) compared to urban areas (30, 36.1%). Caregivers were mainly biological mothers (63, 75.9%), with aunts and grandmothers each at 10 (12.0%). Caregiver education levels were primarily primary (42, 50.6%), followed by secondary (16, 19.3%), diploma (8, 9.6%), no formal education (7, 8.4%), certificate (5, 6.0%), advanced (3, 3.6%), and degree (2, 2.4%) (Table 1, Figure 1).

Prevalence of Malnutrition

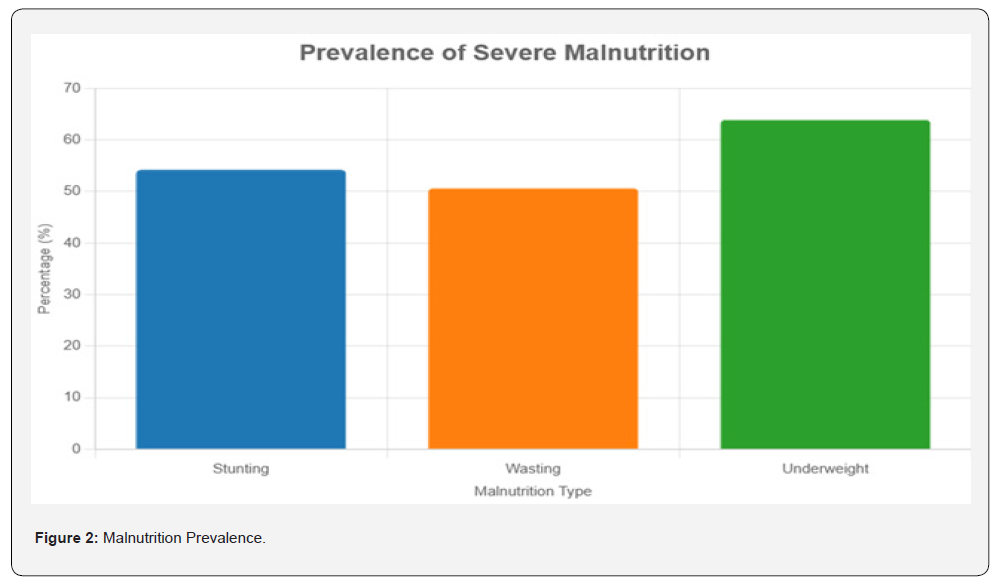

Anthropometric measurements indicated significant malnutrition. The mean age was 17.61 months (SD = 10.55, range: 5–58 months), mean mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) was 11.85 cm (SD = 1.62, range: 4.6–16.4 cm), mean height/length was 72.73 cm (SD = 10.47, range: 53–120 cm), and mean weight was 6.94 kg (SD = 1.79, range: 2.0–12.6 kg). Severe stunting (height-for-age Z-score < -3) affected 45 (54.2%) children, with 19 (22.9%) classified as normal. Severe wasting (weight-for-height Z-score < -3) was observed in 42 (50.6%) children, with 6 (7.2%) normal. Severe underweight (weight-for-age Z-score < -3) was prevalent in 53 (63.9%) children, with 4 (4.8%) normal (Table 2, Figure 2).

Risk Factors Associated with Malnutrition

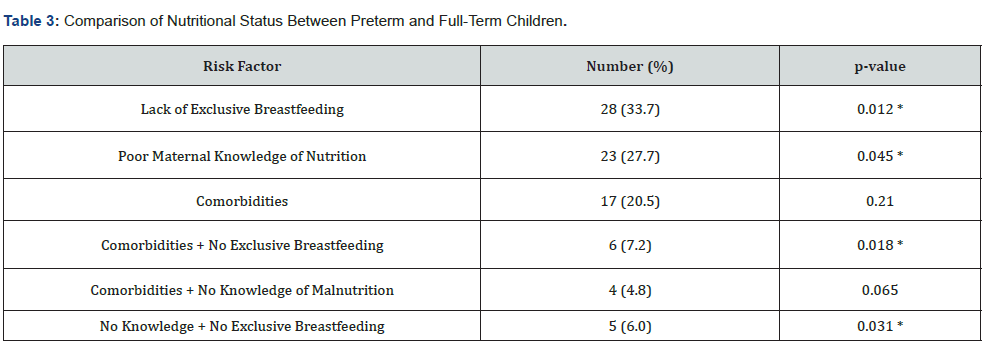

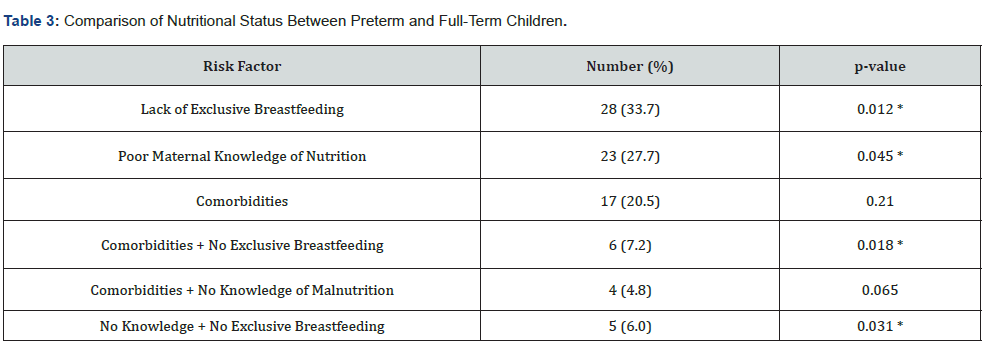

Primary risk factors for malnutrition included lack of exclusive breastfeeding (28, 33.7%), poor maternal knowledge of nutrition (23, 27.7%), and comorbidities (17, 20.5%). Combined factors, such as comorbidities with no exclusive breastfeeding (6, 7.2%), comorbidities with no knowledge of malnutrition (4, 4.8%), and no knowledge of malnutrition with no exclusive breastfeeding (5, 6.0%), were less prevalent (Table 3).

*Statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Comparison of Nutritional Status Between Preterm and Full-Term Children

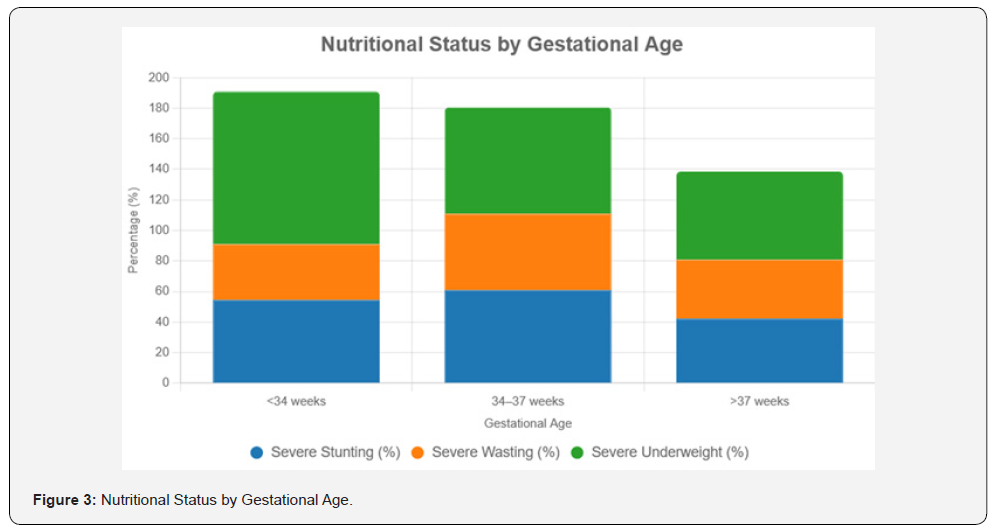

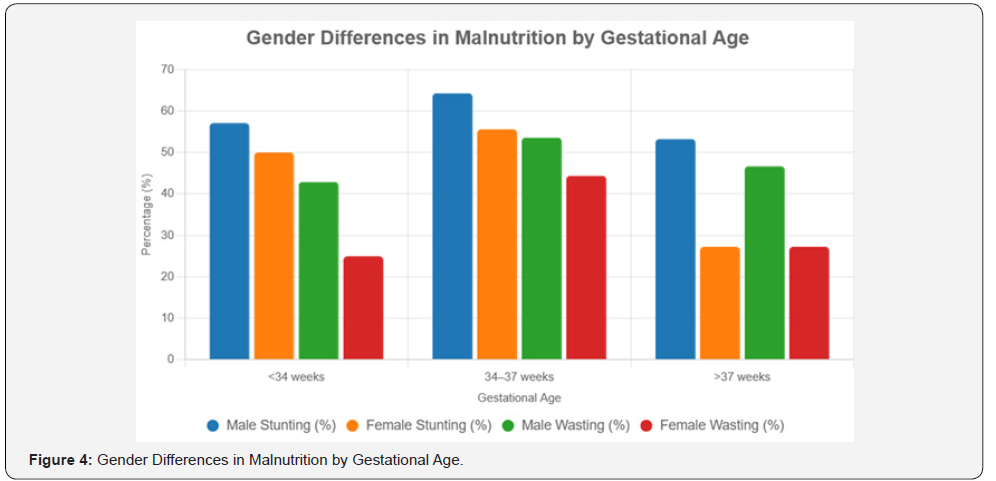

Gestational age distribution showed 46 (55.4%) children born at 34–37 weeks, 26 (31.3%) at >37 weeks (full-term), and 11 (13.3%) at <34 weeks. Severe stunting was most prevalent among children born at 34–37 weeks, while wasting was lowest at <34 weeks. Underweight was widespread, with no children at <34 weeks classified as normal. Males exhibited higher rates of stunting, wasting, and underweight across all gestational age groups compared to females (Table 4, Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

The severe malnutrition observed among young children at Temeke Regional Hospital underscores a pressing public health crisis in Tanzania, particularly in the urban-rural transition zone where access to nutritious food and healthcare remains limited, especially for rural families [10]. Unlike previous studies in other Tanzanian regions that reported less acute nutritional deficits, this research highlights a disproportionate burden in Temeke, likely driven by socioeconomic constraints. The prevalence of caregivers with only primary education reveals a critical barrier: limited knowledge of optimal child-feeding practices. This finding aligns with global evidence linking maternal education to improved nutritional outcomes, suggesting that educational interventions could significantly enhance child health [11]. Each malnourished child represents a family facing systemic challenges, urging the development of targeted, community-based solutions. The study identifies early cessation of exclusive breastfeeding, inadequate maternal nutritional knowledge, and childhood illnesses as key drivers of malnutrition, consistent with established risk factors. Research demonstrates that premature weaning disrupts early growth, increasing vulnerability to nutritional deficits [12]. Caregivers’ limited schooling often restricts their ability to provide balanced diets, exacerbating these risks [13].

Concurrent health conditions, such as infections, further deplete children’s nutritional reserves, a pattern observed in similar low-resource settings [14]. The interplay of these factors underscores the need for comprehensive interventions that address multiple dimensions simultaneously. Programs combining breastfeeding support with nutrition education and health screenings could effectively mitigate these interconnected risks, offering a pathway to healthier outcomes for children. Preterm infants, particularly those born near term, emerge as especially vulnerable, facing heightened nutritional challenges due to immature physiological systems. In resource-constrained settings like Temeke, where specialized care is scarce, these children struggle to meet their elevated nutritional demands, a trend seen across developing countries [15]. While very preterm infants may benefit from targeted medical attention, their small numbers limit definitive conclusions. Compared to full-term peers, preterm children are at greater risk of growth faltering, which can lead to long-term developmental impairments without intervention [16]. These findings emphasize the necessity of tailored nutritional support, such as fortified feeds and regular growth monitoring, to safeguard the health of preterm infants and support their families. The observed gender disparity, with boys experiencing worse nutritional outcomes than girls across gestational ages, introduces a complex dimension to the crisis. Biological factors, such as boys’ higher metabolic demands, may contribute to this vulnerability, as noted in prior research [17]. However, cultural practices in some Tanzanian communities, potentially prioritizing girls in food allocation or care, warrant further exploration [18]. This gender gap highlights the importance of designing interventions that account for both biological and social dynamics. To address malnutrition effectively, Tanzania must implement policies that prioritize the most at-risk groups-preterm infants, boys, and rural families-through accessible education, early detection, and caregiver support, fostering equitable health outcomes for all children.

Conclusion

This study at Temeke Regional Hospital illuminates a critical malnutrition crisis among young children, fueled by early weaning, limited caregiver knowledge, and health challenges, with preterm infants and boys disproportionately affected. It underscores the urgent need for robust nutritional policies in Tanzania, promoting breastfeeding, maternal education, and specialized preterm care. A limitation is the potential for inaccuracies in anthropometric measurements, which may affect data reliability. Future research should integrate precise measurements and community perspectives to design interventions that resonate deeply, ensuring every Tanzanian.

References

- World Health Organization (2023) Malnutrition: Key facts.

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, et al. (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet 371(9608): 243-260.

- Victora CG, Adair L, Fall C, Hallal PC, Martorell R, et al. (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: Consequences for adult health and human capital. The Lancet 371(9609): 340-357.

- UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group (2023) Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates.

- Talbert A, Thuo N, Karisa J, Chesaro C, Ohuma E, et al. (2012) Diarrhoea complicating severe acute malnutrition in Kenyan children: A prospective descriptive study of risk factors and outcome. PLoS ONE 7(6): e38321.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2018) Tanzania national nutrition survey 2018. Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2016) Tanzania demographic and health survey and malaria indicator survey 2015–2016. National Bureau of Statistics.

- United Republic of Tanzania (2016) National multisectoral nutrition action plan (NMNAP) 2016–2021. Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children.

- National Bureau of Statistics, Tanzania (2022) 2022 Tanzania population and housing census. Dar es Salaam: NBS.

- Mlay GA (2021) Nutritional status of under-five children in a rural setting of Tanzania. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 67(3): fmab042.

- Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, et al. (2013) Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 382(9890): 427-451.

- Khan MN, Islam MM (2017) Effect of exclusive breastfeeding on selected adverse health and nutritional outcomes: A nationally representative study. BMC Public Health 17(1): 889.

- Walson JL, Berkley JA (2018) The impact of malnutrition on childhood infections. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 31(3): 231-236.

- Sania A, Spiegelman D, Rich-Edwards J, Okuma J, Kisenge R, et al. (2014) The contribution of preterm birth to the Black-White infant mortality gap, 1990 and 2000. American Journal of Public Health 104(7): 1255-1261.

- Christian P, Lee SE, Donahue Angel M, Adair LS, Arifeen SE, et al. (2013) Risk of childhood undernutrition related to small-for-gestational age and preterm birth in low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Epidemiology 42(5): 1340-1355.

- Thurstans S, Opondo C, Seal A, Wells J, Khara T, et al. (2020) Boys are more likely to be undernourished than girls: A systematic review and meta-analysis of sex differences in undernutrition. BMJ Global Health 5(12): e004030.

- Hadley C, Lindstrom D, Tessema F, Belachew T (2008) Gender bias in the food insecurity experiences of Ethiopian adolescents. Social Science & Medicine 66(2): 427-438.

- Bhutta ZA, Akseer N, Keats EC, Vaivada T, Baker S, et al. (2020) How countries can reduce child stunting at scale: Lessons from exemplar countries. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 112(Supplement_2): 894S-904S.