Abstract

The aim of this multisite randomized controlled trial (RCT) with an intention-to-treat analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing-Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress (EMDR-IGTP-OTS) in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and loss of PTSD or Complex PTSD (CPTSD) diagnostic status, in polytraumatized children and adolescents affected by prolonged adverse childhood experiences, neglect, and maltreatment. A total of 109 children and adolescents (15 males and 94 females) living in 12 social assistance centers under the Mexican government’s protection met the inclusion criteria and participated in a two-day intensive treatment program. Participants’ ages ranged from 7 to 17 (M =11.84 years). A two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) design was applied. Regarding PTSD and CPTSD diagnoses, 63.33% of the Treatment Group participants fulfilled the diagnostic criteria at pre-treatment, whereas only 11.66% still met the criteria at follow-up. This reflects a diagnostic loss of 51.67%. In contrast, 57.14% of the Control Group fulfilled the criteria at pre-treatment, and 69.39% at follow-up, indicating an increase of 12.25% in diagnostic status.

A Chi-square test confirmed that the proportion of participants meeting diagnostic criteria at follow-up differed significantly between groups, χ² (1) = 35.88, p < .001. Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant effects for time (F (2,196) = 147.87, p < .001, η² = 0.60), group (F (1,98) = 12.34, p = .001, η² = 0.11), and a time × group interaction (F (2,196) = 45.67, p < .001, η² = 0.32), indicating significant differences between groups. Independent t tests showed no baseline differences between groups (p = .997, d = 0.001). However, post-treatment (p < .001, d = −1.28) and follow-up (p < .001, d = −2.04) scores were significantly lower in the treatment group, showing a reduction of symptoms. Paired t tests within the treatment group demonstrated substantial reductions from pre-treatment to post-treatment (p < .001, d = 1.14), post-treatment to follow-up (p < .001, d = 0.53), and pre-treatment to follow-up (p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.72). The control group exhibited no significant within-group changes across time points. Results on the Reliable Change Index (RCI) and the Clinically Significant Change (CSC) Margin showed that the ASSYST-I treatment intervention exhibited reliable change on PTSD symptom reduction and clinically significant change. Regarding safety, no adverse effects or events were reported by the participants during the treatment procedure administration or at follow-up. None of the participants showed clinically significant worsening/exacerbation of symptoms after treatment. Participants in the control group received the intervention treatment after the follow-up assessment, fulfilling our ethical criteria.

Keywords:Polytraumatized Children and Adolescents; Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT); EMDR; EMDR-IGTP-OTS; EMDR Intensive Treatment; Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); Complex PTSD (CPTSD)

Abbreviations: RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial; RCTs: Randomized Controlled Trials; EMDR: Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing; EMDR-IGTP: EMDR-Integrative Group Treatment Protocol; EMDR-IGTP-OTS: EMDR-Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress; PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; CPTSD: Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; RCI: Reliable Change Index; CSC: Clinically Significant Change; ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; GDP: Gross Domestic Product; BH: Butterfly Hug; ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision; ITQ-CA: International Trauma Questionnaire: Child and Adolescent Version; IRB: Institutional Review Board; ICMJE: International Committee of Medical Journal Editors; CONSORT: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; SPIRIT: Standard Protocol Items: Recommendation for Interventional Trials; PCL-5: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; DSO: Disturbances in Self-Organization; CAPS-5: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5; NCPTSD: National Center for PTSD

Introduction

Childhood trauma and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs),

which are broadly defined as abuse, neglect, maltreatment, and

household dysfunction, are considered a global epidemic that led

to neurobiological alterations resulting in detrimental impacts on

physical, mental, emotional, and psychosocial health in children,

adolescents, and adults who have experienced ACEs [1]. One way

in which we can see the manifestation of these negative impacts is

in physical health in adults, as various studies show a correlation

between adults who experienced ACEs and exponentially higher

risk for diabetes, heart attack, obesity, cardiovascular and

respiratory diseases, and cancer, and those who have experienced

six or more ACEs die approximately 20 years earlier than those

who have not experienced ACEs [2,3]. Childhood trauma and ACEs

also result in cognitive, emotional, and behavioral issues such

as poor academic performance, problems in language, memory,

inhibition and attention deficits; propensity to depression; altered

arousal level of the amygdala and the fear response which leads

to hypervigilance, enhanced emotional responses, and difficulties

with emotional regulation; changes in the hippocampus, directly

altering the formation of memory; and affected prefrontal cortex

higher order functioning, impeding problem solving, planning,

impulse control, and decision making [4]. Childhood trauma

and ACEs also result in negative consequences for individuals,

families, communities, and society economically. as these

impacted areas put a strain on services, with ACEs accounting for

a significant amount of a country’s annual gross domestic product

[5]. Childhood trauma and ACEs have been found to adversely

alter specific brain structures and neurobiological connectivity.

A systematic review found the following consistencies within

neurobiological and physiological alterations in individuals who

had experienced ACEs:

(1) reduced cortisol responses to stressors;

(2) low-level inflammation;

(3) heightened amygdala responses to emotionally distressing

stimuli; and

(4) Reduced hippocampal grey matter volume, and that these

neurobiological alterations found in posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) are also found in

individuals without the disorder, but who have experienced ACEs,

suggesting that ACEs could be an epidemiological or contributing

factor to the development of PTSD and MDD through these specific

neurobiological alterations [6].

Other studies have identified correlations between specific types of ACEs and childhood trauma and specific neurobiological modulations: sexual abuse was found to be associated with structural deficits in the reward circuit and Genito sensory cortex, emotional abuse is associated with alterations in the frontal limbic socioemotional networks, neglect is associated with white matter integrity and connectivity disruption in several brain networks, autonomic dysregulation was identified as being associated with “severe” types of childhood trauma, and other alterations, such as reduced frontal cortical volume, were common to all types of ACEs [4]. These findings have demonstrated specific structural and functional brain system alterations as a result of exposure to different types of ACEs that can result in various multi-systemic complications.

While the research is limited, evidence shows that “the gene expression patterns of parents who have experienced ACEs or inflicted ACEs on their children could be biologically inherited… Parents’ experience of being abused has been revealed to considerably increase the risk of abusing their own children” (p.15) [6], perpetuating the augmentation of childhood trauma and ACEs, and their subsequent deleterious long-term effects. Given these findings, particularly on the potential perpetuation of childhood trauma and ACEs by those who have experienced ACEs, evidence-based trauma-focused mental health treatment interventions appropriate in the treatment of symptoms and disorders caused by ACEs and childhood trauma are crucial to individual and collective health. Interventions that utilize “approaches to trauma memory processing that address not only memories of specific focal traumatic events but also the impact of cumulative exposure to multiple types of traumatization” are considered optimal for mitigating the effects of childhood trauma and ACEs and in the treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms, PTSD, and Complex PTSD [7]. Emphasis has also been made on the need for interventions that minimize the need for verbalization to overcome potential cultural and developmental barriers, while some researchers suggest the incorporation of art therapy in trauma-treatment interventions with children [8].

v

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is a trauma-focused treatment with a standardized protocol and extensive empirical support [9-15]. It outperforms other therapies in terms of cost-effectiveness [16]. EMDR therapy has been found to be effective in reducing PTSD diagnosis and PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents and is recommended in several clinical practice guidelines [17]. Eleven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated the efficacy of EMDR therapy in reducing PTSD diagnosis and PTSD symptoms among children aged 4-18 years [18].

EMDR-IGTP-OTS

The EMDR-integrative group treatment protocol (EMDR-IGTP) for early intervention was developed by members of the Mexican Association for Mental Health Support in Crisis (AMAMECRISIS) to deal with the extensive need for mental health services after Hurricane Pauline ravaged the coasts of the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero in the year 1997 [19]. It is the first EMDR therapy protocol for individual treatment in a group format. The protocol combines the eight EMDR therapy treatment phases with a group therapy model and an art therapy format. It uses the EMDR Butterfly Hug (BH) as a form of self-administered bilateral stimulation [20,21]. Later, Jarero et al., adapted the EMDR-IGTP to treat older children, adolescents, and adults living with recent, present, or past prolonged adverse experiences (e.g., ongoing or prolonged traumatic stress) and developed the EMDR-IGTP for Ongoing Traumatic Stress (EMDR-IGTP-OTS) [22,23]. Both protocols have the most extensive research in the EMDR early intervention and ongoing traumatic stress field [24]. These protocols have shown effectiveness in the reduction of PTSD symptoms in child victims of severe interpersonal trauma and adolescents with multiple adverse childhood experiences, as well as the epigenetic impact in these population [25-27].

Objective

The objective of this multisite randomized controlled trial (RCT) with an intention-to-treat analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing-Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress (EMDR-IGTP-OTS) in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and loss of PTSD or Complex PTSD (CPTSD) diagnostic status, in polytraumatized children and adolescents affected by prolonged adverse childhood experiences, neglect, and maltreatment.

Method

Study Design

To measure the effectiveness of the EMDR-IGTP-OTS on the dependent variable PTSD symptoms, this study, with an intentionto- treat analysis, used a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) with a waitlist no-treatment control group design. PTSD symptoms were measured at three time points for all participants in the study using the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Time 1. Pre-treatment assessment; Time 2. Posttreatment assessment, and Time 3. Follow-up assessment. To establish the PTSD and Complex PTSD (CPTSD) diagnoses based on the International Classification of Diseases 11 (ICD-11), the International Trauma Questionnaire Child and Adolescent Version (ITQ-CA) was used at two time points for all participants: Time 1. Pre-treatment assessment and Time 3. Follow-up assessment. For ethical reasons, all participants in the control group received the treatment intervention after the follow-up assessment was completed.

Ethics and Research Quality

The research design protocol was reviewed and approved by the EMDR Mexico International Research Ethics Review Board (also known in the United States of America as an Institutional Review Board) in compliance with the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommendations, the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice of the European Medicines Agency (version 1 December 2016), and the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013. The quality of research of this study was based on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 Statement and the Standard Protocol Items Recommendation for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 checklist [28,29].

Participants

This study was conducted in Mexico City and Querétaro City, Mexico, from December 2024 to January 2025, with the Mexican (Latino) child and adolescent population with pathogenic memories from adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), neglect, and maltreatment. To prevent the stigmatization of those who fulfill the inclusion criteria, all two hundred and seventy-five children and adolescents living in the twelve social assistance centers under the Mexican government’s protection were interviewed, randomly assigned to the Treatment or Control Group, and participated in the six EMDR-IGTP-OTS sessions conducted during two consecutive days. Of two hundred and seventy-five, one hundred and nine participants (15 males and 94 females) fulfilled the Inclusion criteria: (a) being a child or adolescent between 7 and 17 years-old, (b) having pathogenic memories from ACEs, neglect, and maltreatment causing current distress, (c) voluntarily participating in the study, (d) not receiving specialized trauma therapy, (e) not receiving drug therapy for PTSD symptoms, (f) having a PCL-5 total score of 30 points or more. Exclusion criteria were: (a) ongoing self-harm/suicidal or homicidal ideation, (b) diagnosis of schizophrenia, psychotic, or bipolar disorder, (c) diagnosis of a dissociative disorder, (d) organic mental disorder, (e) a current, active chemical dependency problem, (f) significant cognitive impairment (e.g., severe intellectual disability, dementia), (g) presence of uncontrolled symptoms due to a medical illness. Participants’ ages ranged from 7 to 17 (M =11.84 years). Participation was voluntary, with the participants and their legal guardians signed informed consent in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Safety and symptoms worsening

We determined the safety of this two-day intensive traumafocused treatment program by recording the number of adverse effects (e.g., symptoms of dissociation, fear, panic, freeze, shut down, collapse, fainting), events (e.g., suicide ideation, suicide attempts, self-harm, homicidal ideation) or clinically significant worsening/exacerbation of symptoms on the PCL-5 reported by the participants during treatment or at follow-up.

Instruments for Psychometric Evaluation

A. We used the Trauma Screen Checklist from the Child

PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and

adolescents for the study participants to choose the traumatic

events they had experienced prior to being removed by the

Mexican government. This list contains 15 frightening or stressful

events that can happen to children, and all of them fulfill DSM-5

PTSD Criterion A. Participants chose the event that bothered them

the most to answer the PCL-5 during the three assessment times

and during the ITQ-CA two assessment times [30].

B. To measure PTSD symptom severity and treatment

response, we used the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

for DSM-5 (PCL-5) provided by the National Center for PTSD

(NCPTSD), with the time interval for symptoms to be the past

week. This weekle administered version of PCL-5 is largely

comparable to the original monthly version [31]. The instrument

was translated and back-translated into Spanish. It contains 20

items. Respondents indicated how much they have been bothered

by each PTSD symptom over the past week using a 5-point Likert

scale ranging from 0=not at all, 1=a little bit, 2=moderately, 3=quite

a bit, and 4=extremely. A total symptom score of zero to 80 can

be obtained by summing the items. The sum of the scores yields

a continuous measure of PTSD symptom severity for symptom

clusters and the whole disorder. Psychometrics for the PCL-5,

validated against the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale-5 (CAPS-

5) diagnosis, suggest that a score of 31-33 is optimal to determine

probable PTSD diagnosis [32-33].

C. To establish the PTSD and Complex PTSD (CPTSD)

diagnoses based on the ICD-11, we used the ITQ-CA 7 to 17 years.

It consists of 12 items with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0

(never) to 4 (almost always). The ITQ consists of three symptom

clusters referring to PTSD (re-experiencing, avoidance, and sense

of threat) and three additional symptom clusters referring to

disturbances in self-organization (DSO; affective dysregulation,

disturbances in relationships, and negative self-concept). The

ITQ-CA diagnostic criteria have not been altered in comparison

to the ITQ. The CPTSD diagnosis is constructed as a combination

of all PTSD symptom clusters and all DSO symptom clusters.

Every symptom cluster consists of two symptoms, and only

severity scores of 2 or higher are used to indicate a symptom.

For both PTSD and CPTSD diagnoses, the endorsement of one

of two symptoms from each symptom cluster and an additional

functional impairment is required. A patient cannot receive both

PTSD and CPTSD diagnoses. The total severity of PTSD and DSO

symptom scores is calculated by, respectively, summing up items

1 to 6 and 7 to 12, with a total ITQ score ranging between 0 and

48 (PTSD+DSO). In addition, the three DSO symptom clusters

separately have an overall scoring range of 0 to 8, with a total DSO

symptom score ranging between 0 and 24 [34,35].

Reliable Change Index and Clinically Significant Change Margin

In this study, we used the Reliable Change Index (RCI) and the Clinically Significant Change (CSC) Margin to determine whether PTSD symptoms change indicates reliable and clinically significant change [36].

Procedure

Randomization, Allocation Concealment Mechanism, and Blinding Procedure

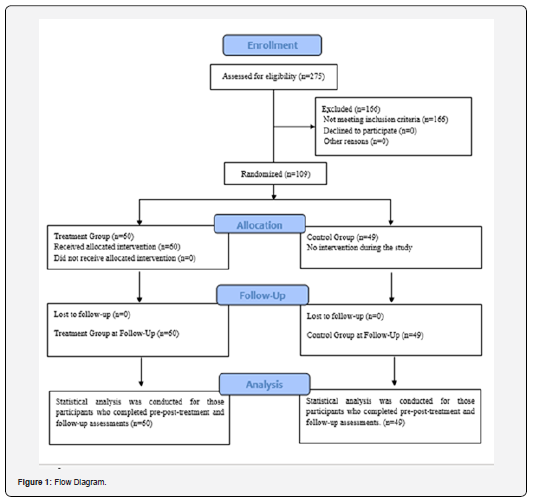

A computer-generated simple randomization with a 1:1 allocation ratio was used for the two hundred and seventyfive children and adolescents living in twelve social assistance centers. Two independent assessors, blind to treatment conditions, conducted the randomization process to avoid allocation influence. The treatment random allocation sequence was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed, and stapled envelopes, opened only after irreversibly assigned to the participants. The safekeeping of the envelopes and the assignment of participants to each arm of the trial (implementation of the random allocation sequence) was overseen by a person not involved in the research study and independent of the enrollment personnel. The participants’ treatment allocation was blinded to the research assistants who conducted the intake interview, initial assessment, and enrollment, as well as the independent assessors who conducted the follow-up assessments. Participants were instructed not to reveal their treatment allocation to those conducting the assessments. Only the data of the one hundred and nine participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria was included in this study. Sixty participants were allocated to the Treatment Group (TG) and forty-nine participants to the Control Group (CG). At pre-treatment assessment, TG had 11 (18.33%) participants who fulfilled the PTSD criteria, 27 (45%) who fulfilled the CPTSD criteria, and 22 (36.66%) who did not fulfill either of those diagnoses. The CG had 8 (16.33%) participants who fulfilled the PTSD criteria, 20 (40.81%) who fulfilled the CPTSD criteria, and 21 (42.85%) who did not fulfill either of those diagnoses (Figure 1).

Enrollment, Assessment Times, Blind Data Collection, and Confidentiality of Data

Treatment Group (TG) and Control Group (CG) participants completed the instruments in person and on an individual basis during distinct assessment moments. During Time 1, research assistants formally trained in all of the instruments’ administration, who were not blind to the study, but blind to the participant’s treatment allocation, conducted the intake interview, collected demographic data (e.g., name, age, gender,), assessed potential participants for eligibility based on the inclusion/ exclusion criteria, obtained signed informed consent from the participants and their legal guardians, conducted the pretreatment application of instruments, and enrolled participants in the study. The research assistants also assisted the participants in identifying the pathogenic memory of their worst adverse experience or Index Event from the Trauma Screen Checklist from the Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents to be treated with the EMDR-IGTP-OTS. Each identified memory (Index Event) was written down by the research assistants on the Memory Record Cards used by the participants during the group treatment and the three assessment times to ensure participants were focusing on the same event when they received the treatment intervention and the specific assessment time when they completed the assessment tools. To obtain maximally interpretable PCL-5 scores and ITQ diagnoses, research assistants and independent assessors a) discussed with each participant the purpose of the instrument in detail, b) encouraged attentive and specific responding, c) invited participants to read each question carefully before responding and to select the correct answer, d) clarified their questions about some of the symptoms, such as differentiating between intrusive memories and flashbacks, e) reworded conceptually complex symptoms (i.e., symptoms in the reexperiencing cluster) when necessary, f) reminded participants of the last-week symptom’s time frame, as well as g) to only report symptoms related to the pathogenic memory of their worst adverse experience (Index Event), and not based on their everyday general distress.

During Time 2 (post-treatment assessment, 7 days after treatment), and Time 3 (follow-up assessment, 30 days after treatment), assessments were conducted for all participants by blind to treatment allocation, independent assessors with formal training in the administration of the instruments. The data safe keeper independent assessor received the participant’s assessment instruments that were answered during Times 1, 2, and 3. All data was collected, stored, and handled in full compliance with the EMDR Mexico International Research Ethics Review Board requirements to ensure confidentiality. Each study participant and their legal guardians gave their consent for access to their data, which was strictly required for study quality control. All procedures for handling, storing, destroying, and processing data were in compliance with the Data Protection Act 2018. All the people involved in this research project were subject to a signed professional confidentiality agreement.

Withdrawal from the Study and Missing Data. All research participants had the right to withdraw from the study without justification at any time and with assurances of no prejudicial result. If participants decided to withdraw from the study, they were no longer followed up in the research protocol. There were no withdrawals or missing data during this study.

Treatment

In this study, EMDR therapy was provided in an intensive format [37,38]. Evidence suggests that more frequent scheduling of treatment sessions maximizes PTSD treatment outcomes [39]. This intensive format allowed the participants to complete the full course of treatment in a short period. Participants in the treatment group completed a total of six treatment sessions provided during two consecutive days, three times a day.

Clinicians and Treatment Fidelity

The EMDR-IGTP-OTS was provided in person by licensed EMDR clinicians who were formally trained in the protocol administration. To protect the minors’ identities, videotapes or pictures were not allowed. The EMDR therapists’ strict observance of all steps of the scripted protocol fulfilled treatment fidelity and adherence to the protocol.

Treatment Description and Treatment Safety

Treatment was provided by licensed EMDR clinicians who were formally trained in the protocol administration. Each treatment group participant received an average of six hours of treatment provided during six group treatment sessions, three times daily, during two consecutive days, inside the twelve social assistance centers. The EMDR-IGTP-OTS treatment focused on the pathogenic memory of their worst adverse experience, or Index Event, from the Trauma Screen Checklist from the Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. During this process, participants followed the directions from the team leader and worked quietly and independently on their pathogenic memories. The first treatment session lasted an average of 95 minutes. Subsequent treatment sessions lasted an average of 50 minutes. The time for rest between sessions lasted an average of one hour. Activities during rest time include watching TV, talking, or resting after lunch. During the protocol’s Phase 2 Preparation, participants learned three self-soothing exercises (i.e., abdominal breathing, concentration on the breath, and recalling a pleasant memory). To encompass the whole traumatic stress spectrum, the team leader asked each of the participants to “Please, with your eyes closed or partially closed, run a mental movie of the whole event in your Memory Record Cards, from right before the beginning until today, or even looking into the future and open your eyes when you finish.” The initial treatment target was the Index Event. In subsequent sessions, the team leader asked participants to run the mental movie again and then to target any memory that was currently disturbing, noticing associated emotions and body sensations.

Participants in this study used the Butterfly Hug (BH) 36 times as a self-administered bilateral stimulation method to process traumatic material. During the BH, participants were instructed to stop when they felt in their body that it had been enough. This instruction allowed for enough sets of bilateral stimulation (BLS) for processing the traumatic material. This helped to regulate the stimulation to maintain the patients in their window of tolerance, allowing for appropriate reprocessing [40,41]. All participants reprocessed more than one pathogenic memory. Clinicians working at the center regularly were in charge of reporting any adverse effects, events, or worsening of symptoms during the study to the research project Clinical Director. The TG participants reported no adverse effects or events during the treatment procedure administration or at the thirty-day follow-up. None of the participants in the TG showed clinically significant worsening/ exacerbation of symptoms on the PCL-5 after treatment.

Examples of the Treated Pathogenic Memories

Participants chose an average of three of the fifteen traumatic events from the Trauma Screen Checklist. Examples of pathogenic memories treated during the EMDR-IGTP-OTS sessions were: a) becoming involved with hitmen and witnessing them beat and kill their girlfriend; b) being repeatedly raped along with their sister by their father; c) being stabbed in the stomach by their father; d) witnessing the violent murder of their father; e) witnessing their father suffocate their mother with a pillow; f) seeing their father attempting to kill their mother with a machete; g) witnessing the murder of their uncle during a family party; h) witnessing their father shooting their mother; i) being repeatedly raped by their uncle and being beaten by their mother for “lying” about it; j) Seeing their mother’s blood on her body after their father beat her; k) seeing their uncle kill their father.

Statistical Analysis

A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to compare PTSD scores (PCL-5) across three time points (T1, T2, and T3) for two groups: the Treatment group and the waitlist no-treatment control group. The analysis also included an interaction effect between time and group. Eta squared (η2) is included for effect size. Independent samples t-tests were conducted to compare PTSD scores between the treatment and control groups at each time point. Paired samples t-tests were conducted to compare PTSD scores within each group across the three time points. Cohen’s d was calculated to estimate effect sizes.

Results

ITQ Diagnoses

Regarding PTSD and CPTSD diagnoses, 63.33% of the Treatment Group participants fulfilled the diagnostic criteria at pre-treatment, whereas only 11.66% still met the criteria at follow-up. This reflects a diagnostic loss of 51.67%. In contrast, 57.14% of the Control Group fulfilled the criteria at pre-treatment, and 69.39% at follow-up, indicating an increase of 12.25% in diagnostic status. A Chi-square test confirmed that the proportion of participants meeting diagnostic criteria at follow-up differed significantly between groups, χ²(1) = 35.88, p < .001.

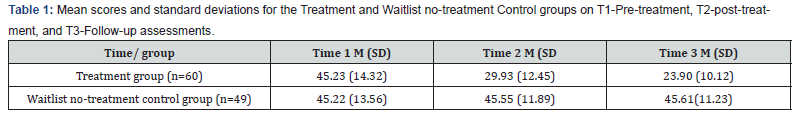

Instruments for Psychometric Evaluation

ANOVA analyses showed a significant main effect of time, F (2,196) = 147.87, p <.001, η2 = 0.60. This indicates that PTSD scores significantly changed over the three points. A significant main effect of group was also found, F (1,98) =12.34, p = .001, η2 = 0.11. The treatment group showed greater reductions in PTSD scores compared to the control group. An interaction effect (time × group) was observed, F (2,196) = 45.67, p <.001, η2=0.32, confirming that the changes in PTSD scores over time differed between the treatment and control groups. Mean comparisons between groups were calculated through independent samples t-tests. Results showed no significant difference between the treatment group (M = 45.23, SD = 14.32) and the waitlist control group (M = 45.22, SD = 13.56) at pre-treatment, t (107) = 0.004, p = .997, Cohen’s d = 0.001. There was a significant difference between the treatment group (M = 29.93, SD = 12.45) and the waitlist control group (M= 45.55, SD = 11.89) at post-treatment, t (107) = −6.73, p < .001, Cohen’s d = −1.28 and there was a significant difference between the treatment group (M = 23.90, SD = 10.12) and the waitlist control group (M= 45.61, SD = 11.23) at follow-up, t (107) = −10.70, p < .001, Cohen’s d = −2.04. Mean comparisons within groups showed a statistically significant decrease for the treatment group comparing scores from pretreatment (M = 45.23, SD = 14.32) to post-treatment (M = 29.93, SD = 12.45), t (59) = 10.34, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.14. There was a statistically significant decrease from post-treatment (M = 29.93, SD = 12.45) to follow-up (M = 23.90, SD = 10.12), t (59) = 4.94, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.53. There was a statistically significant decrease from pre-treatment (M = 45.23, SD = 14.32) to followup (M = 23.90, SD = 10.12), t (59) = 13.25, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.72. Within t-test for the waitlist control group demonstrated that there was no significant change from Time 1 (M = 45.22, SD = 13.56) to Time 2 (M = 45.55, SD = 11.89), t (48) = −0.22, p = .830, Cohen’s d = −0.03. There was no significant change from Time 2 (M = 45.55, SD = 11.89) to Time 3 (M = 45.61, SD = 11.23), t (48) = −0.05, p = .962, Cohen’s d = −0.01 and there was no significant change from Time 1 (M = 45.22, SD = 13.56) to Time 3 (M = 45.61, SD = 11.23), t (48) = −0.28, p = .778, Cohen’s d = −0.04. (Table 1, Figure 2)

Discussion

The aim of this multisite randomized controlled trial (RCT) with an intention-to-treat analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing-Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress (EMDR-IGTP-OTS) in reducing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and loss of PTSD or Complex PTSD (CPTSD) diagnosis status, in polytraumatized children and adolescents by adverse childhood experiences, neglect, and maltreatment. This study evaluated the efficacy of a treatment intervention for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) using PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) scores across three time points (pre-treatment, post-treatment, follow-up) in a treatment group and a waitlist control group. Data from 109 participants (treatment group: n = 60; control group: n = 49) were analyzed via repeated-measures ANOVA, independent- and paired-samples t -tests, and Cohen’s d effect sizes. The results demonstrate a significant reduction in PTSD scores over time in the treatment group, as evidenced by the repeated measures ANOVA and paired samples t-tests. The large effect size (η2=0.60) for the withinsubjects effect of time shows the substantial reduction in PTSD symptoms among participants in the treatment group. In contrast, the control group showed minimal change in PTSD scores across the three time points, with no significant differences observed within the group.

The independent samples t-tests further revealed that the treatment group achieved significantly lower PTSD scores than the control group at T2 and T3, indicating the sustained efficacy of the intervention. These results suggest that the treatment not only reduces symptoms in the short term but also maintains these improvements over time. Although the loss of PTSD or CPTSD diagnostic status was significant with six group sessions, not all participants lost their diagnostic status. One possible explanation is that each participant in the group reprocesses pathogenic memories at a different rate, and six sessions may not be sufficient for their complete reprocessing. Hence, there is a need for more group or individual therapy sessions for these participants in particular. Based on the protocol authors’ fieldwork experience, we recommend conducting a seven-day post-treatment assessment and, depending on the PCL-5 scores, offering three group booster sessions in a one-day intensive format, only to those with PCL- 5 scores over 30 points. These findings suggest the treatment effectively reduced PTSD symptoms, with effects sustained at follow-up. The absence of change in the control group indicates the treatment’s specificity in driving symptom improvement over time. Results highlight the intervention’s potential as a viable therapeutic approach for PTSD.

Conclusions

The prevalence of those who have experienced childhood trauma and ACEs seems to be increasing, with some explanation provided by the recent and novel research in relation to epigenetics and ACEs. While prevention is the first line of defense, unfortunately, prevention is not always possible. When prevention is not possible, we must utilize an evidence-based treatment that demonstrates the effectiveness and safety in treating children who have experienced childhood trauma and ACEs. These treatments must be appropriate not only developmentally and culturally, but also temporally: the treatment of pathogenic memories caused by prolonged or ongoing traumatic stress requires a different approach than those associated with a single-incident PTSD Criterion A traumatic event or adverse experience. The EMDRIGTP- OTS is specifically designed for prolonged or ongoing traumatic stress and incorporates the desired elements of nonverbalization and art therapy and is developmentally and culturally appropriate for children of different cultural, socio-economic, and linguistic backgrounds, making it accessible to a wide range of children and adolescents. This study demonstrates that the EMDR-IGTP-OTS is effective and safe in the provision of trauma treatment to children and adolescents. The hope is that children who are treated early on will avoid those detrimental long-term outcomes and will not perpetuate abuse, neglect, or maltreatment of their own children in the future, resulting in individual, familial, and collective healing.

Limitations and Future Directions

The follow-up assessment at 30 days, due to ethical reasons (providing treatment to the CG participants as soon as possible), is a limitation of this study. We recommend future multicenter randomized controlled trials with an intention-to-treat analysis, with larger samples, follow-up assessment at three- and sixmonths, following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 Statement and the Standard Protocol Items Recommendation for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 checklist.

Data availability statement

Due to privacy concerns, the study participants and their legal guardians were assured that raw data would remain confidential and would not be shared.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude to all the EMDR clinicians and research assistants that participated in this study, and especially to: Paola Careaga Escobar, Laura Alvarado Castellanos, Mariana Zanatta Uribe, Nancy Alvarado Suárez, Guadalupe Ilián Vega Ibarra, Martha Berenice Carrasco Ponce, Renata Valeria Caldiño Díaz, David Yair Lugo Rosas, and Alfonso Poiré Castañeda. We also appreciate the support of the Bocar Family Foundation, Gigante Foundation, Compartamos Foundation, Promotora Social México, Dibujando un Mañana Foundation, and National Monte de Piedad Foundation for their financial support to the Social Assistance Centers that protect the children and adolescents who participated in this study.

References

- Vasiliki Tzouvara, Pinar Kupdere, Keiran Wilson, Leah Matthews, Alan Simpson, et al. (2023) Adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and social functioning: A scoping review of the literature, Child Abuse & Neglect, 139.

- Monnat M, Chandler RF (2015) Long-Term Physical Health Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences. The Sociology Quarterly 56(4): 723-752.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, et al. (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction tomany of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse ChildhoodExperiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine14(4): 245-258.

- Maudgil, S. (2024) Effects of childhood trauma on brain functioning. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Approaches in Psychology 2(4).

- Kafui Sawyer, Samantha Kempe, Matthew Carwana, Nicole Racine. (2024) Global and Inclusive considerations for the future of ACEs research. Child Protection and Practice 3.

- Yuko Hakamata, Yuhki Suzuki, Hajime Kobashikawa, Hiroaki Hori (2022) Neurobiology of early life adversity: A systematic review of meta-analyses towards an integrative account of its neurobiological trajectories to mental disorders. Frontiers Neuroendocrinology 65: 100994.

- Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Fyvie C, Grandison G, Garozi M, et al. (2020) Adverse and benevolent childhood experiences in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and Complex PTSD (CPTSD): implications for trauma-focused therapies. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1): 1793599.

- Gkintoni E, Kourkoutas E, Yotsidi V, Stavrou PD, Prinianaki D (2024) Clinical Efficacy of Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Children (Basel) 11(5):579.

- Shapiro F (2018) Eye movements desensitization and reprocessing. Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd Edtn) Guilford Press, New York, United States.

- Author (2013) Guidelines for the management of conditions that are specifically related to stress. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Guideline Watch (2009) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. American Psychiatric Association.

- Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults (2017) American Psychological Association.

- ISTSS Guidelines Committee (2019) posttraumatic stress disorder prevention and treatment guidelines methodology and recommendations. Oakbrook Terrace.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2018) Post- traumatic stress disorder. Evidence reviews on care pathways for adults, children and young people with PTSD.

- (2017) VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder.

- Mavranezouli I, Megnin-Viggars O, Grey N, Bhutani G, Leach J, et al. (2020) Cost-effectiveness of psychological treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults. PloS One 15(4): e0232245.

- Carlijn de Roos, Julia Offermans, Samantha Bouwmeester, Ramón Lindauer, Frederike Scheper (2025) Preliminary efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for children aged 1.5–8 years with PTSD: a multiple baseline experimental design (N =19), European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 16: 2447654.

- Matthijssen S, Lee C, Roos C, Barron I, Jarero I, et al. (2020) The Current Status of EMDR Therapy, Specific Target Areas, and Goals for the Future. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 14: 241-284.

- Jarero I, Artigas L (2009) EMDR integrative group treatment protocol. Journal of EMDR Practice & Research 3(4): 287-288.

- Artigas L, Jarero I (2014) The Butterfly Hug. In M. Luber (Ed.) Implementing EMDR Early Mental Health Interventions for Man-Made and Natural Disasters. Springer, New York, United States pp: 137-130.

- Jarero I, Artigas L (2025) The EMDR Therapy Butterfly Hug Method for Self-Administered Bilateral Stimulation. Research Gate.

- Jarero I, Givaudan M, Osorio A (2018) Randomized Controlled Trial on the Provision of the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol Adapted for Ongoing Traumatic Stress to Patients with Cancer. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 12(3): 94-104.

- Osorio A, Pérez MC, Tirado SG, Jarero I, Givaudan M (2018) Randomized Controlled Trial on the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol for Ongoing Traumatic Stress with Adolescents and Young Adults Patients with Cancer. American Journal of Applied Psychology 7(4): 50-56.

- Jarero I (2025) EMDR Protocols, ASSYST Treatment Interventions and EMDR Butterfly Hug Method for Early Intervention and Prolonged Adverse Experiences Bibliography. Technical Report.

- Jarero I, Roque-López S, Gómez J (2013) The Provision of an EMDR-Based Multicomponent Trauma Treatment with Child Victims of Severe Interpersonal Trauma. Journal of EMDR Practice & Research 7(1): 17-28.

- Susana Roque-López, Elkin Llanes-Anaya, María Jesús Alvarez-López, Megan Everts, Daniel Fernández, et al. (2021) Mental health benefits of a 1-week intensive multimodal group program for adolescents with multiple adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect 122: 1-11.

- Kaliman P, Cosín-Tomás M, Madrid A, Roque López S, Llanez-Anaya E, et al. (2022) Epigenetic Impact of a 1-week Intensive Multimodal Group Program for Adolescents with Multiple Adverse Childhood Experiences. Scientific Reports 12(1): 17177.

- David Moher, Sally Hopewell, Kenneth F Schulz, Victor Montori, Peter C Gøtzsche, et al. (2010) Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials. (CONSORT) 2010 Statement 340: 869.

- An-Wen Chan, Jennifer M Tetzlaff, Douglas G Altman, Andreas Laupacis, Peter C Gøtzsche, et al. (2013) Standard Protocol Items Recommendation for Interventional Trials. (SPIRIT) 2013 Checklist. Retrieved at 158(3): 200-207.

- Edna B Foa, Anu Asnaani, Yinyin Zang, Sandra Capaldi, Rebecca Yeh, et al. (2018) Psychometrics of the Child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 for Trauma-Exposed Children and Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 47(1): 38-46.

- Darnell CB, et al. (2025) Psychometric evaluation of the weekly version of the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 Sage.

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, et al. (2016) Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders- Firth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess 28(11): 1379-1391.

- Franklin CL, Raines AM, Cucurullo L-A, Chambliss JL, Maieritsch KP, et al. (2018) 27 ways to meet PTSD: Using the PTSD-checklist for DSM-5 to examine PTSD core criteria. Psychiatry Research 261: 504-507.

- Cloitre M, Shevlin M, Brewin C, Bisson J, Roberts N, Maercker A, Hyland P (2018) The international trauma questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica 138(6): 536-546.

- Baker S, Smyth C, Bartholomew E, Buchanan B, Hegarty D (2025) A Review of the Clinical Utility and Psychometric Properties of the International Trauma Questionnaire - Child and Adolescent Version (ITQ-CA): Percentile Rankings and Qualitative Descriptors. NovoPsych.

- Marx BP, Lee DJ, Norman SB, Bovin MJ, Sloan DM (2021) Reliable and Clinically Significant Change in the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 and PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 Among Male Veterans. Psychological Assessment. Advance online publication 34(2): 197-203.

- Hurley EC (2018) Effective Treatment of Veterans With PTSD: Comparison Between Intensive Daily and Weekly EMDR Approaches. Front. Psychol. 9: 1458.

- Bongaerts H, Van Minnen A, de Jongh A (2017) Intensive EMDR to treat patients with complex posttraumatic stress disorder: A case series. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 11(2): 84-95.

- Gutner CA, Suvak MK, Sloan DM, Resick PA (2016) Does timing matter? Examining the impact of session timing on outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 84(12): 1108-1115.

- Ogden P, Minton K, Pain C (2006) Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York, NY: Norton.

- Siegel DJ (1999) The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. New York, NY: Guilford Press.