Abstract

Introduction: The role of nurse practitioners in pediatric emergency rooms is expanding and on-going education and skills training is required to ensure quality care. Simulation is one tool that has been found to be effective in building and maintaining critical procedural skills among pediatric providers. However, longitudinal assessments of these trainings are absent, and therefore little is known about how clinical judgement and skill retention fare over time.

Methods: Utilizing a longitudinal interventional design, effects of a pediatric and adult resuscitation simulation curriculum for pediatric nurse practitioners were examined by assessing clinical judgment and knowledge retention and/or degradation at baseline, followed by intervals of six and 12 months. Qualitative analyses were also performed regarding nurse practitioner perspectives on simulation content, the utility of simulation in building experience and confidence, and the utility of simulation in learning psychomotor procedure skills.

Results/Findings: Several improvements related to clinical judgement, namely data prioritization and dedication to improvement, were identified among participants. This study also found that knowledge levels increased slightly at six months but decreased slightly at 12 months. Furthermore, only half of the participants felt moderately comfortable leading codes after a year of simulation trainings.

Conclusion: Results suggest that while simulation is valuable, future research is needed to improve measurement of clinical judgement and enhance participants’ knowledge and confidence beyond just the immediate post simulation period.

Keywords:Simulation; Nurse Practitioners; Emergency Medicine; Clinical Judgment; Pediatrics

Abbreviations: NPs: Nurse practitioners; EDs: emergency departments; ABA: American Burn Association; ACS: American Colleges of Surgeons; ACLS: Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support; PALS: Pediatric Advanced Life Support; ENPC: Emergency Nursing Pediatric Course; IRB: Institutional Review Board; LCJR: Lasater Clinical Judgement Rubric

Introduction

Nurse practitioners (NPs) have been frontline providers in emergency departments (EDs) across the United States for nearly fifty years [1], and emerging research suggests that the role of nurse practitioners in pediatric emergency departments continues to grow [2,3]. Furthermore, NPs work in a variety of areas within the emergency department with a majority reporting caring for patients with urgent conditions [4]. Therefore, NPs must be prepared to care for both acutely and critically ill patients, including the ability to respond to complex and deteriorating patient scenarios, perform critical care procedures, and participate in resuscitation. However, while NPs report exposure to a variety of patients and the need to perform a multitude of procedures, extant research demonstrates the need for more education and on-the-job training, as this format is how most nurse practitioners report optimal skill acquisition [4]. Current literature examining pediatric nurse practitioners also reveals reported desires for additional postgraduate training to manage emergent situations involving children, including skills related to airway management, shock management, and rhythm disorders [3]. Finally, as children are accompanied in the emergency department by adults, it is important to be able to recognize and emergently treat the adult caregivers who may suffer from medical emergencies during the pediatric emergency department visit. While pediatric nurse practitioners are trained and board certified to care for children, they must be able to initiate rapid and prompt emergent intervention for these adult patients until they can be stabilized and transferred to adult healthcare providers.

Simulation has been identified as a safe, low risk teaching modality that, under the right conditions, allows learners to acquire and practice clinical skills with increasing complexity [5]. The utility of simulation-based training has been examined across a variety of interdisciplinary settings, including among attending physicians, residents, nurse practitioners [6], nurse practitioner students [7], and among students studying in other health profession curricula [8]. With regards to simulation specific to pediatric emergency and critical care, several studies have examined the use of simulation to practice the management of pediatric emergencies with findings that support improved cognitive performance [9], time to resuscitation, team performance, and team leader performance [10] as well as improved provide confidence, skill level, and communication skills [11] in emergency situations.

While simulation is a promising tool to enhance provider communication, teamwork, and skill execution, there is also a great need to understand how knowledge and skills developed or reinforced in pediatric simulations are retained over time. For example, Yusuf et al. [3] implemented a comprehensive curriculum that included procedural workshops and simulation, and found that advanced practice providers, including nurse practitioners, demonstrated an increase in knowledge at six months without a significant decline at twelve months. However, among adult emergency residents and physicians, Ansquer et al. [12] reported that skill performance after a simulation-based training was best within the six months following training and that skills decrease after the six-month mark to a complete loss of skills at four years.

Skill-reinforcement sessions have been suggested as a method to improve retention over time. As an example, Jani et al. [13] conducted a partially double-blind, controlled study, and found that pediatric residents who participated in a simulationbased PALS refresher curriculum four months after initial PALS training had a statistically significant improvement in their overall retention scores at eight months after the initial PALS course, as compared to those who did not receive the simulation intervention. Further, Stephenson and colleagues [6] designed a comprehensive complex airway management simulation program for neonatal nurse practitioners with the intent to assess skill retention at six months post implementation and found similar skill retention to baseline results [6].

Clearly, research related to skill retention following simulation,

especially over time remains inconclusive and research about skilltraining

reinforcement remains in its infancy. Further, to these

authors’ knowledge, research has not been conducted on clinical

judgement following simulation among pediatric emergency

room nurse practitioners, leaving a large gap in the literature.

Therefore, to expand on what is currently known about the utility

of simulation in pediatric emergency departments, this study

sought to create a pediatric and adult resuscitation simulation

curriculum for pediatric nurse practitioners in the pediatric

emergency department and assess its feasibility at several time

intervals (baseline, six months, and 12 months). To achieve this

goal, the following specific aims were developed:

• Aim 1: To assess nurse practitioner clinical judgment

at baseline, six months, and 12 months using a validated clinical

judgment rubric.

• Aim 2: To assess knowledge retention and/or

degradation at time intervals zero, six, and 12 months using a

multiple-choice assessment.

• Aim 3: To perform a qualitative analysis of nurse

practitioner perspectives at zero, six, and 12 months on

simulation content, the utility of simulation to build experience

and confidence, and the utility of simulation to learn psychomotor

procedure skills, in addition to suggestions for improvement.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in a pediatric emergency department as part of a free-standing children’s hospital in a major metropolitan city. The hospital is designated as a level-one trauma center and a pediatric burn center by the American Burn Association (ABA) and the Committee on Trauma of the American Colleges of Surgeons (ACS). The emergency department has 40 beds, including four resuscitation bays, and sees approximately 60,000 patients per year.

Participants

Thirteen nurse practitioners were evaluated in this study. Fifteen nurse practitioners were approached during recruitment via work email and in-person recruitment approaches, and thirteen consented to participate. Refusal to participate by the other two nurse practitioners was explained by impending decision to terminate position in the workplace. Eligibility criteria required that participants were credentialed and board-certified advanced practice providers in the emergency department with experience caring for patients ranging in age from neonates to young adults. Ten providers were pediatric nurse practitioners with acute care board certification. Two providers were pediatric nurse practitioners with primary care certification, and one was board certified as a family nurse practitioner. All participants were certified in basic and advanced pediatric life support. All providers were credentialed to perform airway and resuscitation procedures on pediatric patients. Experience level as a nurse practitioner ranged from one year to 11 years.

Study Design

This study followed a longitudinal interventional study design. The medical director of the emergency department, in conjunction with a physician colleague and an experienced nurse educator who was certified in providing resuscitation curriculum (Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS), Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and Emergency Nursing Pediatric Course (ENPC)), developed this longitudinal educational curriculum which consisted of multiple simulationbased resuscitation scenarios, as a pilot program for ongoing simulation-based education of emergency department providers. This curriculum was specifically designed to assess clinical judgement, knowledge levels, and to increase team-leading resuscitation skills of the nurse practitioners. Simulation scenarios were designed around resuscitation cases that have the highest rates of occurrence and/or morbidity and mortality in the emergency department. Scenarios followed a format of team simulation followed by facilitated debriefing and procedural skills practice. Each simulation day consisted of three scenarios, two with pediatric patients and one with an adult patient. All simulations were conducted using department-owned simulation technology. The simulation equipment used included the SimMan 3G and SimBaby from Laerdal Medical Corp, and the defibrillator used was the Zoll R Series (Zoll). Feedback from these systems was provided on the simulated patient monitor. Procedural skills training included practicing airway management, intraosseous line placement, and defibrillator use. The curriculum was carried out during a 12-month period using three-month intervals. This study was reviewed by the Central Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB) (#2021357) and deemed to be exempt.

Measures

Data were collected over a 12-month period at three-time intervals: baseline, six months, and 12 months starting in July 2023 and ending in July 2024. Clinical judgment was assessed at baseline, six months, and 12 months using the Lasater Clinical Judgement Rubric (LCJR) [14]. Knowledge retention and/or degradation was evaluated using a multiple-choice assessment. Pre- and post-simulation questionnaires captured participants’ comfort levels as code leaders and with adult patient cases. Both quantitative and qualitative assessments of nurse practitioners’ perspectives related to the utility of simulation were also administered.

Lasater Clinical Judgement Rubric (LCJR)

The LCJR was used to evaluate each nurse practitioner’s clinical judgment skills during simulation at each time interval. Clinical judgement as defined by Tanner [15] is “an interpretation or conclusion about a patient’s needs, concerns, or health problems, and/or the decision to take action (or not), use or modify standard approaches, or improvise new ones as deemed appropriate by the patient’s response” (p. 204). The LCJR was developed by Lasater using the four phases of the Clinical Judgment Model created by Tanner [15]: noticing, interpreting, responding, and reflecting. To define the phases of clinical judgement, noticing indicates the ability to gather and recognize information, interpreting signifies prioritizing and understanding relevant information as it relates to a patient’s condition, responding refers to communication skills, intervention/flexibility, and the use of nursing skills, and reflecting involves self-evaluation and commitment to improvement [16]. The LCJR was selected for this study as it has been found to be a reliable and valid instrument among nursing students in various settings and because it provides a standard language to discuss clinical judgement with participants during debriefing [17]. In this study, the LCJR was used to evaluate nurse practitioners’ simulation performances based on the four phases of clinical judgment (noticing, interpreting, responding, and reflecting) and 11 items on which participants were evaluated as beginner, developing, accomplished, or exemplary. LCJR scores range from 11 to 44, with higher scores indicating better clinical judgment [18].

Knowledge Quiz

The knowledge quiz was a 10-item multiple choice quiz. Participants were asked questions pertaining to the management and resuscitation of infants, children, and adults. This included questions related to physical assessment, airway management, critical procedures, cardiac rhythms and medication management.

Pre- Post-simulation Questionnaires

Pre- and post-simulation questionnaires queried participants about their comfort as a code leader, their comfort level with adult patient critical cases and codes, and the usefulness of simulation. These questionnaires included items about postgraduate training satisfaction, relevance of simulation to job role, if simulation would enhance clinical practice, if simulation should be required, and if respondents would like regularly scheduled simulation training. The post-simulation questionnaire asked questions about the simulation, including whether participants found the simulation devices to be realistic, if simulation was a safe learning environment and good use of time, and if simulation taught or reinforced airway-management skills and critical-procedure skills. Other questions also gauged participants’ feelings about debriefing and interest in future simulation exercises.

Qualitative Questionnaire

The qualitative questionnaire asked additional open-ended questions about the number of simulation training workshops participants had previously attended, whether participants viewed the simulation as a good use of time, how participants envisioned future simulations, and what they felt worked or did not work with the simulation. Participants were also asked to provide feedback about content they would like added to the simulations.

Data Analysis

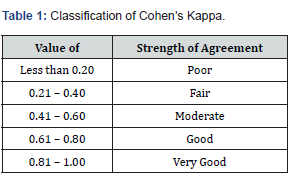

All quantitative analyses were performed using SPSS 29.0 (IBM, NY) statistical software program. Cohen’s Kappa (K) was used to examine inter-rater reliability by two physician raters who utilized the Lasater Clinical Judgement Rubric to evaluate clinical judgement and determine participants’ proficiencies in noticing, interpreting, responding, and reflecting to key elements in the scenario. Nonparametric Related Samples Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance was utilized to examine results of the ten-item skills quiz at baseline, six months, and 12 months. Descriptive statistics were used to report results from the pre- and post-simulation surveys. Finally, qualitative analysis was carried out using basic thematic analysis.

Results

Clinical Judgement Interrater Reliability

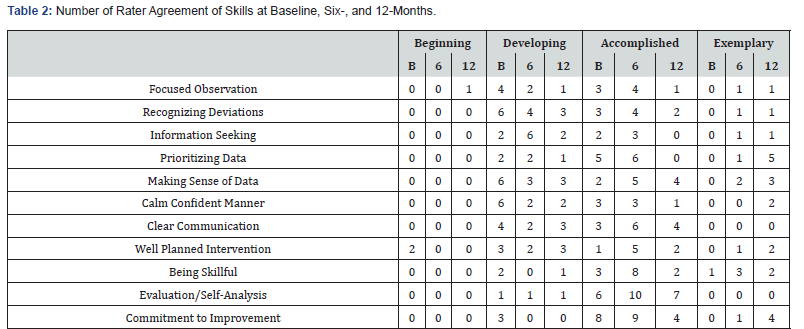

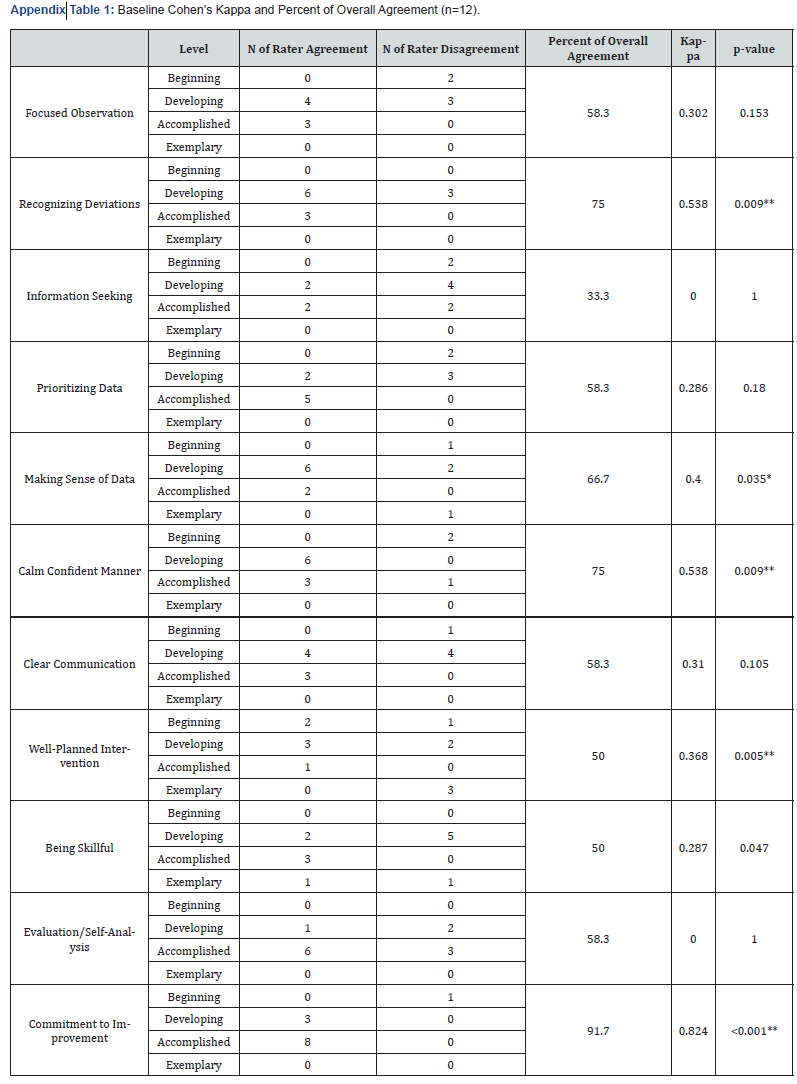

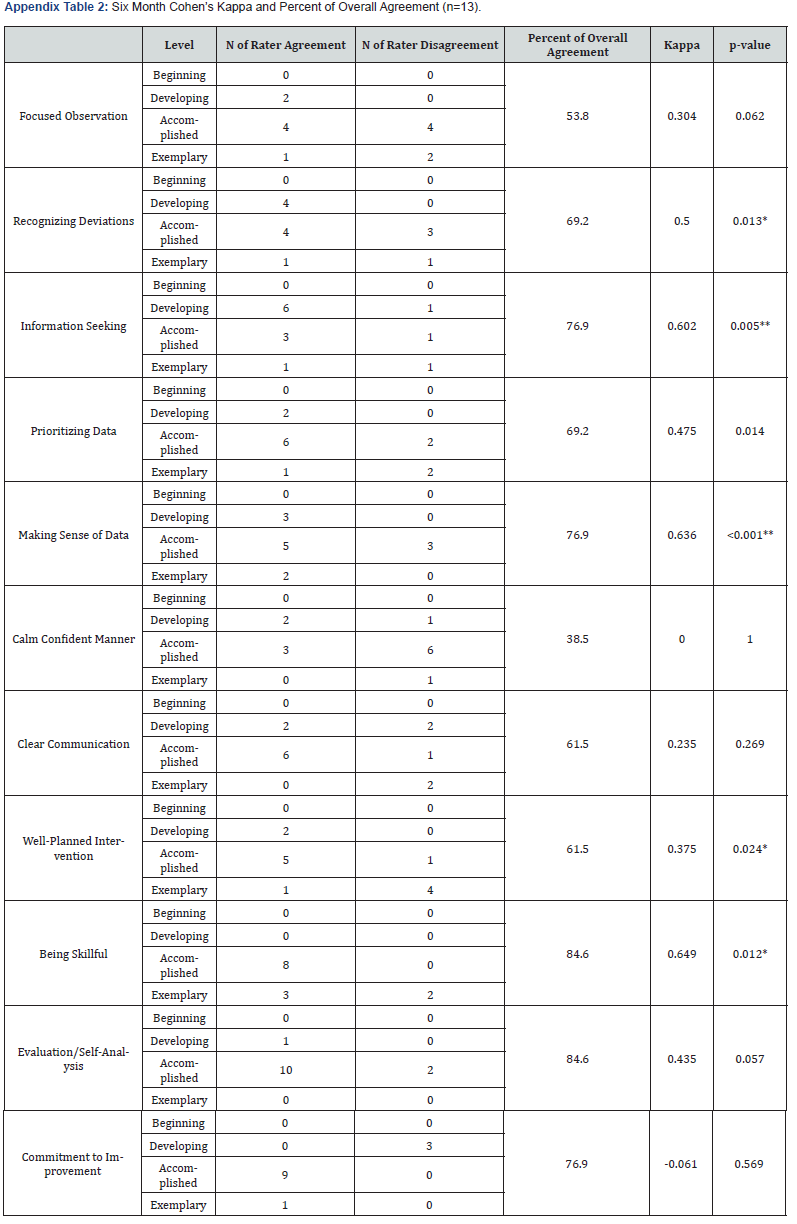

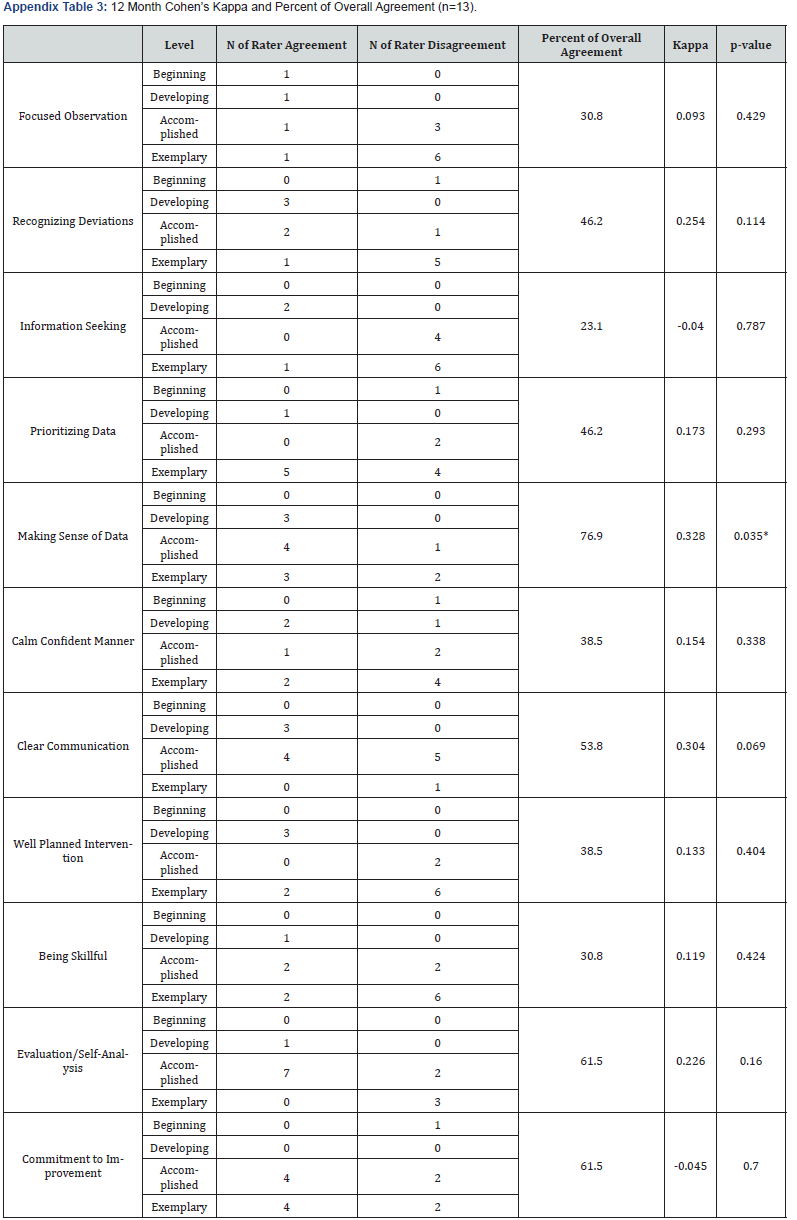

Two raters utilized the LCJR to determine the participants’ proficiencies in four areas at three intervals. Cohen’s Kappa (K) was used to examine inter-rater reliability. The classification of Cohen’s Kappa is presented in Table 1. There were 13 participants at baseline; all participants performed the six- and 12-month simulation exercises with zero attrition. At baseline, five of the 11 ratings (45.5%) between the raters were significant at either the 0.01 or 0.05 levels (see Appendix for detailed tables of all three time periods). The highest K was 0.824 for “commitment to improvement.” All 13 participants were present for the six-month simulation exercises. Six of the 11 ratings were significant (54.5%) at the 0.01 or 0.05 levels. The highest K was 0.649 for “being skillful,” and the K for “commitment to improvement” dropped to -0.061. For the 12-month exercises, one of the K results (0.328 for “making sense of data”) was significant (9.0%), p = .035. The largest agreed-upon gain in skills over time was for “prioritizing data,” with the raters agreeing on five of the participants displaying exemplary skills; this area was followed by “commitment to improvement”. There appeared to be a slight degradation of skills for “focused observation,” as the raters agreed on a beginning level for one participant at 12 months when there was no agreement on a beginning level at baseline or six months. Agreement on the demonstration of developing or accomplished skills also decreased at 12 months for “focused observation” (Table 2).

Participant Clinical Judgement

Few ratings of exemplary were provided at baseline with the following exceptions: “information seeking” (8.3% for one rater), “making sense of data” (8.3% for one rater), “well planned intervention” (25.0% for one rater), and “being skillful” (16.7% for one rater and 8.3% for the other). Exemplary and accomplished percentages were then averaged between the two raters. Skills with the three highest average percentages of exemplary and accomplished at baseline were “evaluation/self-analysis” (35.4%), “commitment to improvement” (33.3%), and “being skillful” (31.3%). The lowest three were “focused observation”, “recognizing deviations”, and “calm confident manner” (all 14.6%).

Exemplary and accomplished ratings increased in all cases at six months except for “information seeking” where a slight decrease was observed (rater 1 rating decreased for accomplished from 33.3% to 30.8%, and rater 2 rating for exemplary decreased from 8.3 to 7.7 and for accomplished decreased from 58.3% at baseline to 38.5%). 12-month ratings varied; increases in average percentages were observed from six months with “focused observation” (32.7% to 34.6%), “recognizing deviations” (28.8% to 30.8%), and “information seeking” with the largest improvement (23.1% to 32.7%). Decreases from six months were observed with “prioritizing data” (38.5% to 36.5%), “calm confident manner” (32.7% to 30.8%), “clear communication” (36.5% to 32.7%), “well planned intervention” (40.4% to 34.6%), “being skillful” (50.0% to 42.3%), “evaluation/self-analysis” (42.3% to 40.4%), and “commitment to improvement” (44.2% to 40.4%). “Making sense of data” did not change between 6 and 12 months (32.7%).

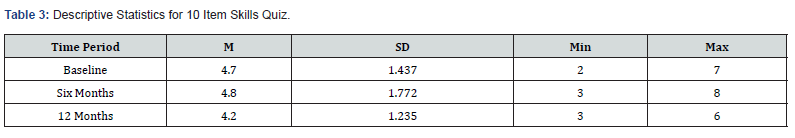

Knowledge Quiz

The participants took a ten-item resuscitation focused knowledge quiz at baseline, six months, and 12 months. Mean scores increased slightly at six months (4.7 to 4.8) and decreased slightly at 12 months (4.8 to 4.2) (Table 3). Given the small sample size and lack of normality, the nonparametric Related Samples Kendall’s Coefficient of Concordance was conducted; the results were not significant (Kendall’s W = 0.016, p = 0.811).

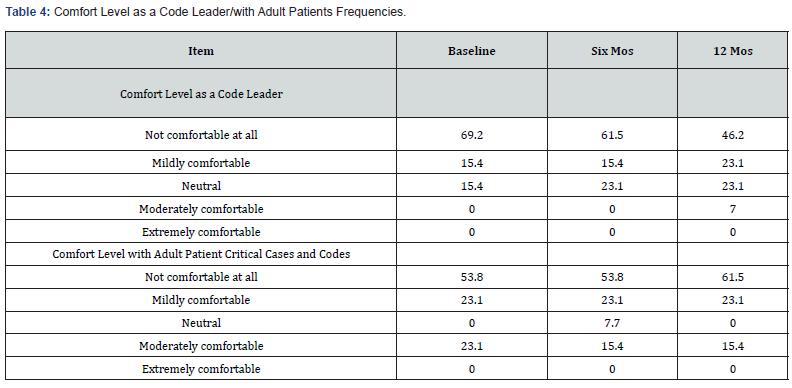

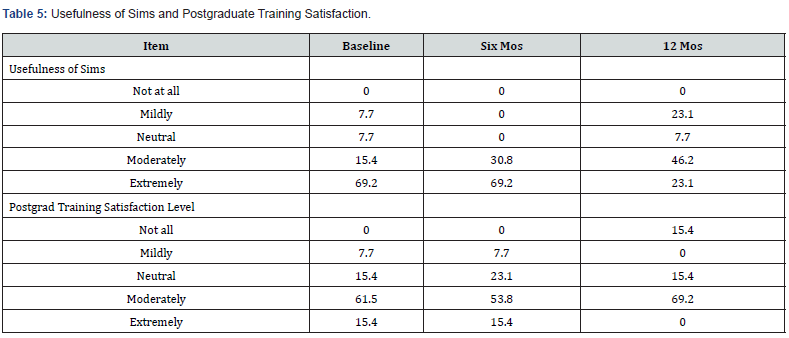

Pre-simulation Questionnaire 1

Participants reflected on the confidence they had in their abilities before taking part in the simulation. Respondents evaluated their comfort as a code leader and their comfort levels with adult patient critical cases and codes using a rating scale of extremely comfortable, moderately comfortable, neutral, mildly comfortable, and not comfortable at all. For comfort level as a code leader, approximately two-thirds of the participants did not feel comfortable at all. This comfort level decreased to under half at 12 months. Comfort level with adult patient critical cases and codes decreased somewhat at 12 months. No participant indicated feeling extremely comfortable at any point for either question (Table 4). The usefulness of simulations and the postgraduate training satisfaction levels were rated as not at all, mildly, neutral, moderately, and extremely. Participants endorsed simulations as being more useful at six months (where 100% rated them as moderately or extremely useful) than at either baseline or 12 months. Satisfaction with the postgraduate training decreased after six months (Table 5).

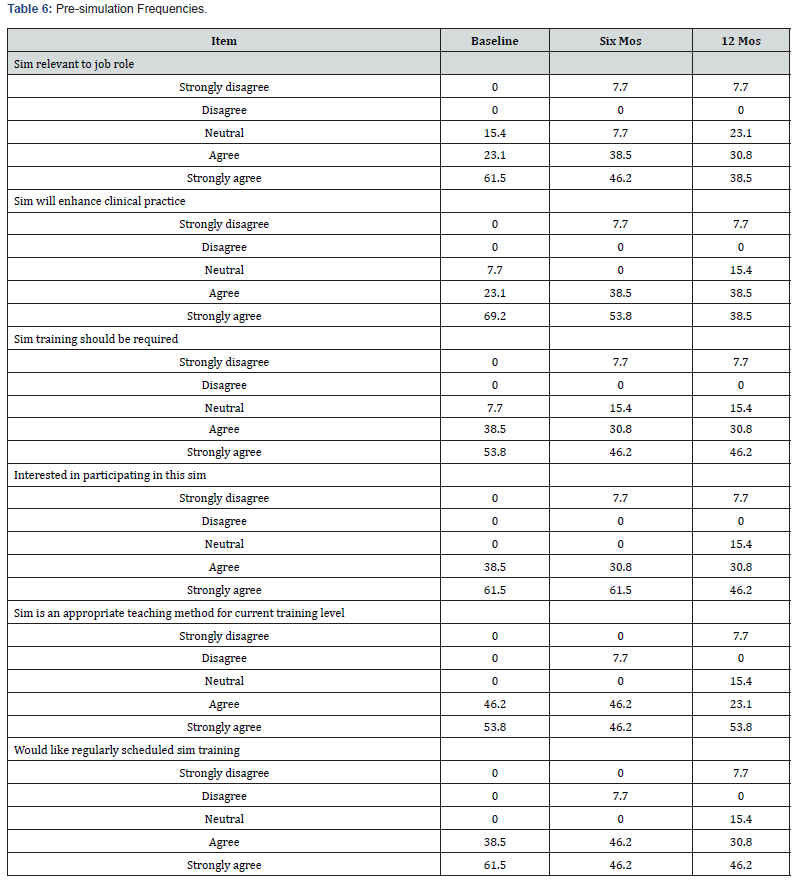

Pre-simulation Questionnaire 2

Participants responded to an additional questionnaire regarding their attitudes toward simulations before participating. The rating options for the second set of pre-simulation questions were strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree. Agreement scores degraded slightly toward twelve months overall (Table 6).

Participants responded to a questionnaire regarding simulations after completing them. The ratings for the postsimulation questions were strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree. Agreement scores were found to degrade slightly toward twelve months overall (Table 7).

Qualitative Questionnaire

During the baseline data collection, five nurse practitioners reported having attended more than 10 postgraduate training workshops utilizing simulation since starting their career. At all data collection timepoints, most participants felt that the simulation was a good use of their time, citing that “the content was great review” (Participant 1) and the simulation environment provided “…a safe space to practice” (Participant 4) as well as learn new procedural skills (Participant 9).

When respondents were asked what they would have liked to have seen done differently, answers varied from wanting more didactic content on some of the simulation case scenarios to wanting more hands-on practice with specific skills, such as intubation. Most participants reported the desire to attend three to four simulation workshops throughout the year to review and maintain skills. When asked to identify what barriers nurse practitioners face in incorporating simulation training into real-life practice, nine NPs reported being assigned too many non-trauma shifts where these skill sets are not utilized, as well as being skipped over by ED attendings during opportunities to perform these skills in favor of having residents or fellows perform them instead. Respondents expressed the desire to learn at the bedside from experienced ED attendings in real patient situations, in addition to receiving a debriefing from ED leadership after every code. All participants reported feeling as though simulation workshops would have been beneficial during employee orientation and reported a preference for simulation training over self-paced instructional modules.

Discussion

This research study examined the effects of a 12-month educational program that focused on simulation-based training for nurse practitioners working in a pediatric emergency department, with a specific emphasis on pediatric and adult resuscitation skills. Nurse practitioners are an integral part of the care in the ER, with an expanding and evolving role. However, only recently has literature begun to explore the preparation and continued education of pediatric nurse practitioners in emergency settings. This study contributes to emergency clinical practice by exploring how PNPs respond to a longitidunal resuscitation simulation curriculum. This includes findings that directly discuss the utility of simulation, the retention of skills overtime, and the need for reinforcement of learning in order maintain skill proficiency.

Several notable findings were identified. First, there were few ratings of exemplary performance at baseline which suggests that pediatric nurse practitioners benefit from additional support and training beyond what is provided in graduate school. This information coupled with current literature that suggests that NPs request and desire this training [3], makes a strong argument for simulation-based training in the post-graduate period. Next, given that exemplary and accomplished ratings increased in all cases at six months except for “information seeking” where a slight decrease was observed, results suggest that simulation has the potential to augment several key components of nurse practitioners’ clinical judgement in the immediate six months after training. However, since 12-month ratings demonstrate improvement in only three areas (“focused observation”, “recognizing deviations” and “information seeking”) and degradation in a majority of others (“prioritizing data”, “calm confident manner”, “clear communication” “well planned intervention”, “being skillful”, “evaluation/self-analysis” and “commitment to improvement”), additional training and reinforcement is needed in order to improve participants’ knowledge and confidence beyond the immediate period following simulation. Looking at individual skills, findings demonstrate that skills were not uniform across all individuals or abilities. Significantly, the practice of “focused observation” revealed a decrease in some participants over time. Therefore, future research should address the importance of comprehending the aspects that impact individuals’ learning paths and tailoring post-graduate education to address these individual needs, as well as creating techniques to improve participants’ retention of skills over time.

The designed simulation-based curriculum in this study emphasized numerous abilities, with airway skills being an important example. There was a decline observed in the rater results regarding the training of airway skills in this cohort. These results are not consistent with previous studies, which has found that teaching airway management and collaborative skills using simulation-based medical curricula is an effective technique to impart such abilities [19]. The significance of the results in this study are unclear – especially given the previous research that supports the use of simulation-based training in airway management. It is possible that participants in this study desired and needed additional teaching that went beyond the scope of what was offered in the simulation. Additionally, given that several participants in this study commented on the need and desire for exposure to patients with complex and critical medical conditions during their actual work shifts, it is also possible that a lack of exposure to patients who require airway management outside of the simulation environment left participants without adequate opportunity to apply the skills learned during simulation, which in turn impacted retention of these skills.

Regarding the improvements in procedural skills, the assessments of NPs in the designed study were variable. Procedural skills are essential in the field of pediatric emergency medicine, but the restricted occurrence of specific types of cases curtails the experience of healthcare providers. Therefore, while simulationbased medical education enables the practicing of infrequent medical techniques and enhances provider confidence [20], these types of educational programs may benefit from offering dedicated shifts that allow for exposure to various procedures. Individual mentoring may also be of benefit.

Additionally, two-thirds of participants initially reported feeling extremely uncomfortable about leading codes, indicating a clear need for assistance and instruction at baseline. Over time, there was a small increase in comfort ratings as a code leader for pediatric patients and a small decrease during codes involving adult patients at 12 months. As evidence of the ongoing difficulty in building readiness and confidence, just half of the participants felt moderately comfortable regarding codes at 12 months, demonstrating the need for additional training in this area. We recommend more simulation opportunities as well as versatility in training modality. Further, given that nine out of the thirteen NPs reported being assigned too many non-trauma shifts where critical skill sets are not utilized and the desire to learn at the bedside from experienced ED attendings in real patient situations, offering nurse practitioners the opportunity to be involved in codes and code management with mentorship is likely to be of most value in improving abilities. This is especially true given previous research that demonstrates that limited clinical experience hinders pediatric emergency medicine providers from acquiring essential procedural and collaboration skills [12] which in turn could influence the quality of care provided.

Clinical judgment was evaluated by two separate ED attendings, and measures of interrater reliability showed that the agreement between evaluators fluctuated widely at different time periods, suggesting some difficulties in maintaining consistent assessment using the tool. For example, while there was greater interrater reliability on the notion of “being skillful”, the category “commitment to improvement,” did not have consistent consensus, as there was a decrease over time. These results indicate possible variations in the understanding and assessment of these characteristics among raters. Given that the LCJR was developed for use with nursing students, further research that examines the use of the LCJR with this population of pediatric nurse practitioners or with emergency medicine physicians as raters, would be warranted.

Finally, analysis of the qualitative questionnaire indicated that participants perceived the simulation as both a valuable allocation of their time and a secure environment for acquiring new procedural skills and honing previously acquired skills. Most participants expressed a preference for attending three to four simulation workshops annually to review content and maintain their abilities.

Limitations

The limited sample size of this study hinders the generalizability of its findings. Secondly, there was a dearth of quantitative data pertaining to the execution of crucial procedures. The absence of statistical significance in the knowledge quiz results may be attributed to the limited sample size and deviation from normal distribution. The study’s dependence on self-reported levels of comfort was susceptible to social desirability bias and could fail to precisely reflect the individuals’ actual comfort levels.

Conclusion

This research examined the effects of a longitudinal simulationbased curriculum on the pediatric and adult resuscitation skills for pediatric emergency medicine nurse practitioners over the course of 12 months. While individuals demonstrated significant growth during simulation scenarios, objective test scores indicated a minor decrease in confidence and clinical judgment at twelve months. These results shed light on participants’ longterm retention of critical skills and knowledge learned during simulation trainings. Simulation evaluations demonstrated the observation of participant skill development in many areas. However, the inconsistency of ratings between different evaluators over time highlights the need for improved evaluation techniques and evaluator training. Future studies are needed to further study findings and continue the longitudinal assessment of resuscitation skill retention and knowledge in this population of healthcare providers (Appendix 1-3).

References

- Cole FL, Kleinpell R (2006) Expanding acute care nurse practitioner practice: Focus on emergency department practice. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 18(5): 187-189.

- Iqbal A U, Whitfill T, Tiyyagura G, Auerbach M (2024) The role of advanced practice providers in pediatric emergency care across nine emergency departments. Pediatric Emergency Care 40(2): 131-136.

- Yusuf S, Hagan JL, Stone S (2022) A curriculum to improve knowledge and skills of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the pediatric emergency department. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners 34(10): 1116-1125.

- Cole FL, Ramirez E (2000) Activities and procedures performed by nurse practitioners in emergency care settings. Journal of Emergency Nursing 26(5): 455-463.

- McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, Scalese RJ (2010) A critical review of simulation- based medical education research: 2003-2009. Medical Education 44(1): 50-63.

- Stephenson E, Salih Z, Cullen DL (2015) Advanced practice nursing simulation for neonatal skill competency: a pilot study for successful continuing education. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 46(7): 322-325.

- Keiser MM, Turkelson C (2019) Using Simulation to Evaluate Clinical Performance and Reasoning in Adult-Geriatric Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Students. The Journal of Nursing Education 58(10): 599-603.

- Turkelson C, Keiser M, Yorke A, Smith L (2018) Piloting a multifaceted interprofessional education program to improve physical therapy and nursing students' communication and teamwork skills. Journal of Acute Care Physical Therapy 9 (3): 107-120.

- Donoghue AJ, Durbin DR, Nadel FM, Stryjewski GR, Kost SI, et al. (2009) Effect of high-fidelity simulation on pediatric advanced life support training in pediatric house staff: a randomized trial. Pediatric Emergency Care 25(3): 139-144.

- Harwani TR, Harder N, Shaheen NA, Al Hassan Z, Antar M, et al. (2020) Effect of a pediatric mock code simulation program on resuscitation skills and team performance. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 44: 42-49.

- Thim S, Henriksen TB, Laursen H, Schram AL, Paltved C, et al. (2022) Simulation-based emergency team training in pediatrics: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 149(4): e2021054305.

- Ansquer R, Mesnier T, Farampour F, Oriot D, Ghazali DA (2019) Long-term retention assessment after simulation-based-training of pediatric procedural skills among adult emergency physicians: A multicenter observational study. BMC Medical Education, 19(1): 348.

- Jani P, Blood AD, Park YS, Xing K, Mitchell D (2021) Simulation-based curricula for enhanced retention of pediatric resuscitation skills: A randomized controlled study. Pediatric Emergency Care 37(10): e645-e652.

- Lasater K (2007) Clinical judgment development: using simulation to create an assessment rubric. The Journal of nursing education 46(11): 496-503.

- Tanner Christine (2006) Thinking Like a Nurse: A Research-Based Model of Clinical Judgment in Nursing. Journal of Nursing Education 45(6): 204-211.

- Miraglia R, Asselin ME (2015) The Lasater Clinical Judgment Rubric as a framework to enhance clinical judgment in novice and experienced nurses. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development 31(5): 284-291.

- Victor-Chmil J, Larew C (2013) Psychometric properties of the Lasater Clinical Judgment Rubric. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship 10(1): 45-52.

- Adamson K A, Gubrud P, Sideras S, Lasater K (2012) Assessing the reliability, validity, and use of the Lasater Clinical Judgment Rubric: Three approaches. Journal of Nursing Education 51(2): 66-73.

- Nguyen L, Bank I, Fisher R, Mascarella M, Young M (2019) Managing the airway catastrophe: Longitudinal simulation-based curriculum to teach airway management. Journal of Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery 48(1): 10.

- Sagalowsky ST, Wynter SA, Auerbach M, Pusic MV, Kessler DO (2016) Simulation-based procedural skills training in pediatric emergency medicine. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine17(3): 169-178.