Spiritual Care in the NICU from the Parents’ Perspective: A Mixed Methods Study

Keren Genstler1*, Alexis Barajas Terrones1, Brittany Chow1, Kristopher Roxas1, John Tan1, Barbara Couden Hernandez1, Douglas Deming1 and Chad Vercio1,2

1Loma Linda University Health, 11234 Anderson St, Loma Linda, CA 92354

2Riverside University Health System, 26520 Cactus Ave, Moreno Valley, CA 92555

Submission: September 14, 2022; Published: December 01, 2022

*Corresponding author: Keren Genstler, MD, Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital, Division of Neonatology, 11175 Campus St. Suite 11121, Loma Linda, CA 92350-1700, Tel: (909) 651-5746; Fax: (909) 558-0298

How to cite this article:Genstler K, Terrones AB, Chow B, Roxas K, Tan J, et al. Spiritual Care in the NICU from the Parents’ Perspective: A Mixed Methods Study. Acad J Ped Neonatol 2022; 12(2): 555889. 10.19080/AJPN.2022.12.555889

Abstract

Objective: The importance of whole person care interventions is increasingly appreciated in the literature. Spiritual care is one of these dimensions and has been desired by a large percentage of clinical populations in critical care situations. A typical assumption is that spiritual care would be provided by chaplains. There is limited research exploring parents’ perspectives on spiritual care from the medical team in general and from physicians particularly. The objective of this study was to further elucidate the parent experience on receiving spiritual care from varied members of the medical team.

Methods: An anonymous survey was distributed to parents and caregivers at a single institution. A smaller subset of parents were further interviewed in order to obtain qualitative data which was analyzed using a general inductive approach.

Results: Quantitative and qualitative data were collected from the caregivers and legal guardians of NICU patients in the form of 108 quantitative surveys and 16 qualitative interviews. Parents indicated openness to receiving spiritual care from various members of the medical team and did not have strong barriers to receiving various types of spiritual care, nor significant barriers to receiving spiritual care from those of differing faiths or spiritual beliefs.

Conclusion: Guardians typically expect spiritual care from chaplains, however this study demonstrates caregivers also appreciate spiritual care from other members of the healthcare team including their physician. This validates the importance of educating physicians in how to provide spiritual care for families in critical care settings.

What’s new: Literature is increasingly demonstrating the importance of spiritual care to families and patients. Limited studies explore the experience of NICU families who receive spiritual care from physicians and medical care team members.

Keywords: spiritual care, spiritual belief, religious, whole person care, neonatal intensive care unit, physician

Abbreviations: NICU, HOPE tool, FICA

Introduction

Whole person care has been increasingly recognized as a critical dimension in the practice of medicine [1-4]. It involves considering all aspects that affect the patient and family’s experiences, from emotional, spiritual, psychosocial, or financial perspectives in addition to medical pathophysiology [5]. Previous studies demonstrate that spirituality is an important source of strength and resilience for patients and their families [2,6-10]. However, many of these sentinel studies were completed decades ago and it is reasonable to question whether these represent the contemporary desires of society. The focus of neonatal practitioners typically focuses on physical well-being; however emotional, psychosocial, and spiritual support are each important aspects of care given to families in the neonatal intensive care unit [9] and assists patient families cope by giving hope and meaning to a difficult moment in life [11]. Spiritual care involves finding a deeper connection and creating a pathway to find meaning with others [9]. Victor Frankl has provided a framework for understanding that in times of deep suffering humans are capable of finding hope and meaning [12]. Spirituality is one important way that humans are able to develop meaning in their suffering and also find avenues for hope therefore is an important access point for relationships with parents in the NICU.

Spiritual care has been described by Christina Pulchalski, and includes listening, being present and compassionate, asking about spiritual background and preferences, and incorporating those practices as appropriate [4]. A large percentage of the US population is spiritual and believes in a higher power [13]. Over 80% of Americans share the belief that prayer can increase the likelihood of recovering and over 70% endorse the belief that God can cure patients, regardless of what medical science supports.

Previous studies have demonstrated a desire amongst patients and patients’ families to discuss spirituality and religion in medical settings as these both can have a significant impact on their experience of their illness. In a meta-analysis of 54 studies with >12,000 participants, it was found that a majority of patients express interest in discussing spiritual concepts [2,14] and in some areas in the country, a majority (~90%) of hospitalized patients use religion as a key component in accepting their disease with 40% using it as the primary mechanism to cope [11] This has particularly been true for the critical care setting when questions such as the value, purpose, and meaning of life are brought to the surface [9,15,16]. Studies done in adult and pediatric ICU settings showed that serious illness or end of life and palliative care increase the desire for spiritual care [10,17]. The intervention of spiritual care before and after a significant traumatic event or in an end of life setting can help in one’s grieving process [9]. A study consisting of over 3,000 patients identified the importance of spiritual care and supported the claim that addressing spiritual needs increases trust and satisfaction [18]. The NICU is a setting of uncertainty for parents where the questions of suffering, meaning and value may surface and cause distress.

Historically, a common assumption is that spiritual professionals such as chaplains or faith group leaders provide spiritual care [19]. It is less typical for healthcare providers such as physicians and nurses to provide religious or spiritual care [20]. However, in 2011, 76% of pediatricians stated that spirituality and religious concerns are an important component of their practice in medicine. Despite this view, only ~10% incorporate it into their routine practice [9]. It is likely that many physicians do not feel comfortable providing spiritual or religious care, or may not feel that it is their place [21]. Others feel that physicians on occasion could offer spiritual intervention, but only if members of the chaplaincy or others specifically spiritually trained are not present [22]. Often there is hesitation in providing spiritual care due to the varied background of spiritual and religious perspectives. Providers are uncertain how to provide interfaith spiritual care due to lack of training [23]. Thus, spirituality is integral to many patients and families’ experience in life and particularly their experience in the hospital setting. While several studies have demonstrated the positive effects on clinicians from compassion rounds [24] or otherwise including spiritual care in their medical practice, the perspectives of parents in the NICU and their experiences receiving spiritual care from physicians is currently underreported. This study aims to explore the experience of parents in our NICU and their viewpoint of receiving spiritual care from physicians, in addition to their perspective on interfaith spiritual care.

Methods

Study design

The study was designed to gather information from primary caregivers or legal guardians, primarily parents of patients hospitalized at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital NICU, regarding the spiritual care they desired to receive. The local institutional review board approved this study. The goals of the study were to (i) understand the importance of spiritual care from various members of the medical team, from physicians and nurses to chaplains and social workers, (ii) understand if there were preferences or differences in experience for spiritual care from those varied roles, (iii) obtain a rich description of the experience of families receiving spiritual care from the medical team, specifically from physicians.

Inclusion criteria involved parents or guardians who had a child/children currently admitted to the NICU and were able to read English or Spanish. Exclusion criteria included inability to read English or Spanish. Study personnel asked participants to complete a single paged, anonymous survey consisting of 14 questions ranging from religious demographics to Likert scale questions comparing desire for spiritual care intervention and importance of spirituality in daily life. Questions on the importance of spirituality in daily life were taken from a previously validated spirituality survey [25]. Informed consent was obtained at the time of enrollment prior to survey participation. Following survey completion, parents were asked if they would be willing to engage in a further interview at a later time. Sixteen parents completed an in person, phone or online interview. The interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis using the general inductive approach. In this approach, textual data is condensed into a summary format of themes and links are evaluated. Then a framework is developed from the experiences described in the data [26].

Data analysis

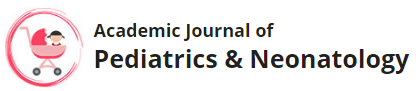

Likert scale questions were assigned numerical values and standard descriptive statistics were produced. For the qualitative portion, four authors (B.C., K.R., A.B., K.G.) independently analyzed the transcripts of the interviews for thematic evaluation using a general inductive approach [26]. Each coder developed a list of emerging themes by first identifying responses to each interview question. Secondly, the remainder of each transcript was examined to identify related comments for each theme that were stated in response to other questions. Third, each theme was examined to determine sub themes that further defined the meanings and variations within each theme. The team then met together to compare and negotiate theme names and meanings, creating a code book with the results. Trustworthiness of the analysis of the data was accomplished through multiple reviews of the data with the developed themes and sub-themes as well as the review by two experienced research team members (C.V., B.H.) who performed secondary checks and evaluated the results. A model (Figure 1) was developed from the major themes that emerged from the data: the spiritual and emotional components of spiritual care, with sub themes of qualifications and professions that provide spiritual care and the experience of receiving it. These themes and sub themes are discussed in detail below.

Results

Religious breakdown and other demographics

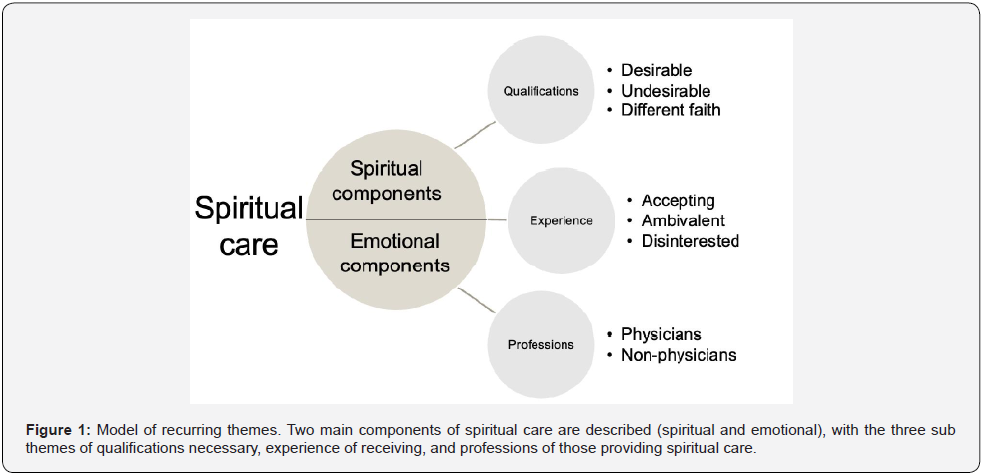

The participants in the study had similar religious demographics to the United States as stated by the PEW research center, with 70.37% of the 108 participants identifying as a type of Christian [27,28] (Table 1). Our participants primarily chose to respond in English, with only 2 of 108 surveys completed in Spanish. The participants had a broad spectrum of NICU stay experience with varying lengths and full spectrum of ages of prematurity and various disease presentations. Mean length of NICU stay was 18.3 days, with a minimum of 1 and maximum of 99 days. Mean gestational age was 33.34 weeks, ranging from 23 to 41 weeks gestational age at birth.

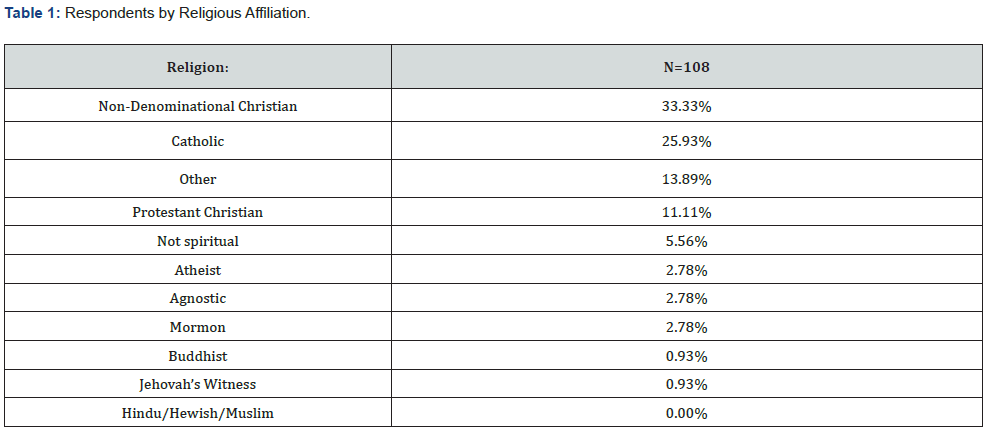

The terms religion and spirituality are often used interchangeably. Religion is often described as the individual or group practice of beliefs and rituals involving the transcendent. Spirituality is often defined as the belief in something larger, or a higher power, outside oneself [11]. However, despite these definitions there is much overlap between religion and spirituality. The survey administered used questions from previously validated surveys to determine the respondent’s spirituality [25]. The participants were actively spiritual and found meaning and importance in spiritual things (Figure 2). In regards to spirituality of the participants at baseline, parents responded to three questions on the importance of spirituality in their daily life (from 1 = very unimportant to 5 = very important with mean of 4.2, SD of 1.0), if they sought comfort in spiritual things (1 = never/almost never and 6 = Many times a day, with mean of 4.6, SD 1.6), and if they asked for divine help (1 = never/almost never and 6 = many times a day, with mean of 4.1, SD 1.7).

Quantitative data on spiritual care from members of the healthcare team

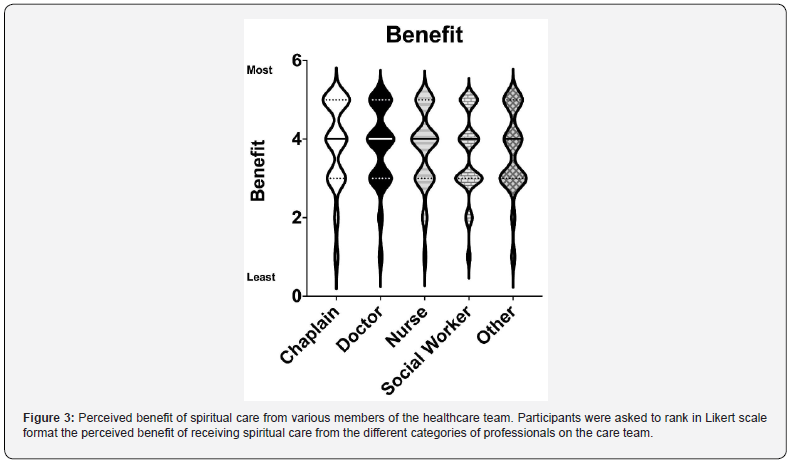

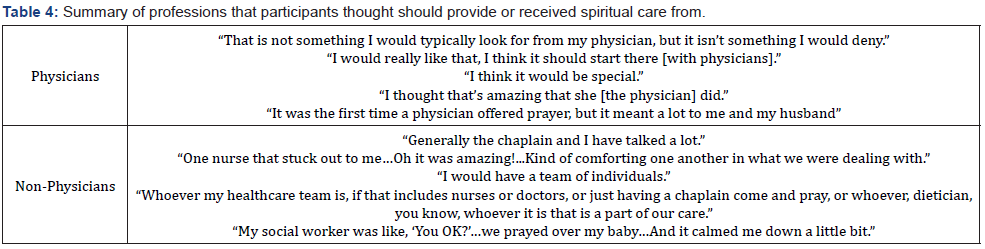

A majority of parents responded either neutrally or favorably when asked if they benefited from spiritual care from medical members of the healthcare team. In response to questions on perceived benefit of spiritual care from members of the healthcare team, 33% responded that they feel they would benefit from spiritual care from a physician and 28% felt they would strongly benefit, 28% would feel neutral benefit, 4.6% disagreed with feeling benefits, and 3.7% strongly disagreed with feeling benefits, with 2.8% who chose not to respond. (Figure 3). Participants were also asked to rank their preference of professions to provide spiritual care. 79 of 108 survey respondents completed this ranked question. Parent responses indicated they felt they could primarily benefit from spiritual care from chaplains, followed by physicians, ranking highest in the agree and strongly agree responses (Figure 4).

Qualitative data on spiritual care from members of the healthcare team

Throughout the qualitative interviews, participants expressed appreciation for spiritual care provided by various medical team members. Figure 1 provides the model for the following findings. Two significant overarching components of spiritual care emerged: emotional and spiritual support. The emotional component was described as providing “a sense of comfort and relief and encouragement,” and “empathizing, sympathizing with you” and “being present”. Participants expressed the spiritual component as involving prayer, “having someone say, ‘Let me pray for you’”. Additionally, spiritual care included specific religious aspects beyond prayer, such as religious rites like “...saying the verses and referring to the Bible” and “they prayed and baptized her, and I got a lot of comfort from it”. Other non-religious aspects that were cited as having spiritual benefits were being encouraged to get outdoors and listening to music. The participants described three major aspects regarding spiritual care from members of the healthcare team: qualifications necessary to provide spiritual care, the experience of receiving spiritual care, the professions of those providing spiritual care.

Qualifications necessary to provide spiritual care

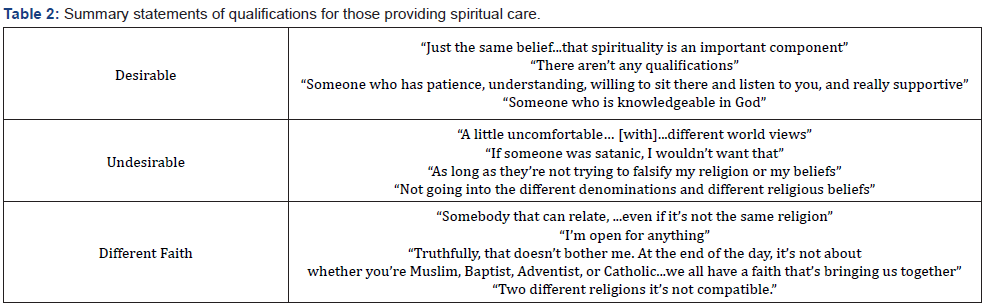

Participants expressed that “There are so many people from different backgrounds who don’t necessarily believe the same thing, but they’re there for you, I think that’s what matters most”. Participants ranged from desiring few qualifications for who provided their spiritual care, “I’m open for anything” and “It wouldn’t matter to being more reserved, “…two different religions, it’s not compatible”. Desirable qualifications included similar beliefs, a sense of presence, patience, and being knowledgeable about God (Table 2). Responses included the spiritual care provider having “the same belief...that spirituality is an important component”. Undesirable qualifications included providers not sharing the same beliefs, with some participants being “a little uncomfortable…[with] different world views,” or “not going into the different denominations and different religious beliefs”. Qualifications for spiritual care from one of a different faith were described as “willing to sit there and listen to you”0 (Table 2).

Experience of receiving spiritual care

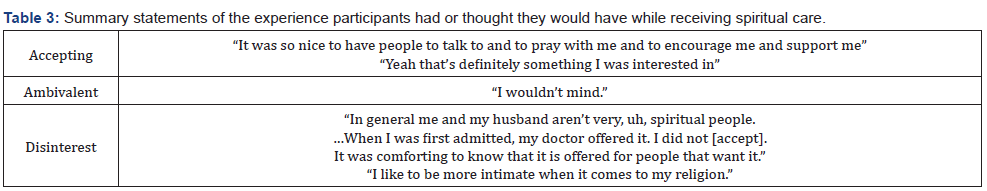

Participants were generally accepting of spiritual care from various members of the medical team, “It was so nice to have people to talk to and to pray with me and to encourage and support me”. Table 3 summarizes the experiences participants had or wished to have in receiving spiritual care. Several respondents were ambivalent, reporting, “I wouldn’t mind”. Others expressed disinterest: “I like to be more intimate when it comes to my religion”. One participant stated, “In general me and my husband aren’t very spiritual people… When I was first admitted, my doctor offered it. I did not [accept]. It was comforting to know that it is offered to people that want it”.

Professions providing spiritual care

Participants described whom they believed should provide spiritual care from a variety of professions, with one participant stating “I would have a team of individuals”. In regard to spiritual care from a physician, one participant said, “That is not something I would typically look for from my physician, but it isn’t something I would deny”, while others reflected, “I think it should start there [with physicians],” and “I think it would be special”. A mother was admitted with high blood pressure who recalled being terrified of the terms, “Severe” pre-eclampsia and the barrage of unfamiliar medication names: “It was the first time a physician offered prayer, but it meant a lot to me and my husband”. Respondents’ perspectives are summarized in Table 4 as to the professions they thought should provide spiritual care, or professions from whom they received care.

Discussion

The findings of this study regarding families’ experience receiving spiritual care from members of the medical team may change how providers give care if replicated and confirmed in future research. The patient and family desire for discussion of religion and spiritual care in medical settings is well documented in the literature [2,17]. Many sentinel articles on spiritual care were published several decades ago leaving many wondering if the results from those studies are still applicable, given the values and cultural shifts in society. This study offers a contemporary view of the desires for spiritual care interventions. Historically the expectation has been for spiritual care professionals such as chaplains, priests, etc., to be the sole providers of anything spiritual or religious related. Although faith leaders and chaplains are considered the providers of spiritual care in hospitals, the qualitative and quantitative results provide evidence that NICU families can appreciate spiritual care intervention from a variety of healthcare team members, including and not limited to physicians and nurses. Providers may fear that if they do have dissimilar same spiritual beliefs from the patient or family that the discussion of spiritual matters would be unwanted. The results of this study demonstrate that NICU families are often open to receiving spiritual care from providers of a variety of faith backgrounds.

Unfortunately, there is often a lack of awareness as well as absence of training for physicians and medical professionals to provide the spiritual aspect of holistic care [29]. Additionally, there is division amongst physicians as to whether they feel comfortable providing spiritual care [30]. Various models and acronyms have been created to assist physicians in knowing how to introduce spiritual care such as HOPE questions (H: sources of hope, O: organized religion, P: personal spirituality and practices, E: effects on medical care and end of life issues) and FICA tool (F: faith and belief, I: importance, C. community, A: address in care) [13]. Future efforts should be made to educate physicians about these tools and how to provide appropriate spiritual care. Such training and education could also positively affect the parent’s experience in receiving spiritual care from physicians.

There are several limitations of this study. It was performed at a single center, which is a faith-based academic institution, as such the healthcare team providers such as physicians and nurses may have some training in providing spiritual care. Even without formal training, it is likely the staff at this institution have seen spiritual care modeled more frequently and may be more comfortable providing it than at other institutions. This experience could improve the families’ experience in receiving care. The families that are admitted in our NICU may also expect more spiritual care than at other centers given the religious affiliation. It is also possible that the respondents could be more religious than at other institutions, however participant religious demographics reflected those of the larger United States population. The results were also similar to previous studies demonstrating significant interest for spiritual care interventions [2,14].

Due to the nature of a large academic unit, data was not collected on the faith background of the nursing, physician, and chaplain staff that provided the spiritual care in this study. Families discussed their openness for spiritual care from a variety of faith backgrounds. However, it is unknown whether they experienced receiving spiritual care from a provider of a differing faith, which could affect the perspectives of the participants.

With regards to demographics, the results were from a relatively small number of participants, and these results may not be widely generalizable. The participants largely responded in English, which could imply a narrow cultural focus. However, many of the participants chose to respond in English despite the opportunity to respond in Spanish as the language of their cultural heritage. Replication of the study with a wider demographic pool would be helpful to determine generalizability. One potential limitation is that all participants in the interviews were female. Some studies have demonstrated that females have a stronger predisposition to benefiting from psychosocial spiritual healing than males [31]. It is possible that the study shows that women respond favorably to spiritual care intervention from healthcare professionals, however the interplay of gender and spiritual care offerings must be further investigated.

There is a growing body of evidence supporting the role of whole person care in medicine, with spiritual care being important to a majority of patients and families. There is also an increased desire for spiritual interventions in end of life and critical care settings [4,6,8-10,32]. Typically, the expectations are for a chaplain to provide any spiritual care, however there is growing evidence that families appreciate spiritual intervention from a variety of providers in the medical team [7,9,33]. The quantitative and qualitative data from this study suggests that many parents of our NICU families indicated they would benefit from spiritual care from the medical team. Those who experienced a physician providing spiritual care had an overall positive encounter. Spiritual care from the family’s perspective can have emotional and spiritual aspects and is acceptable even from those of differing faith backgrounds.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Financial disclosures.

References

- Pulchalski CM (2002) Spirituality and end of life care. In: A Berger, R. Portenoy, and D. Weissman. Principles and practice of palliative care and supportive oncology (2d ed.), ed. Pp. 799-812.

- Best M, Butow P, Olver I (2015) Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns 98(11): 1320-1328.

- Koenig HG, Larson DB, Larson SS (2001) Religion and coping with serious medical illness. Ann Pharmacother 35(3): 352-359.

- Pulchalski C, Ferrell B. Making Health Care Whole: Integrating Spirituality.

- Thomas H, Mitchell G, Rich J, Best M (2018) Definition of whole person care in general practice in the English language literature: a systematic review. BMJ Open 8(12): e023758.

- Madrigal VN, Carroll KW, Faerber JA, Walter JK, Morrison WE, et al. (2016) Parental Sources of Support and Guidance When Making Difficult Decisions in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. J Pediatr 169: 221-226.e4.

- Arutyunyan T, Odetola F, Swieringa R, Niedner M (2018) Religion and Spiritual Care in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit: Parental Attitudes Regarding Physician Spiritual and Religious Inquiry. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 35(1): 28-33.

- MacLean CD, Susi B, Phifer N, Schultz L, Bynum D, et al. (2003) Patient preference for physician discussion and practice of spirituality. J Gen Intern Med 18(1): 38-43.

- Rosenbaum JL, Smith JR, Zollfrank R (2011) Neonatal end-of-life spiritual support care. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 25(1): 61-69; quiz 70-71.

- Hexem KR, Mollen CJ, Carroll K, Lanctot DA, Feudtner C (2011) How parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care use religion, spirituality, or life philosophy in tough times. J Palliat Med 14(1): 39-44.

- Koenig HG (2012) Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012: 278730.

- Frankl VE (1985) Man’s Search For Meaning. Simon and Schuster.

- Saguil A, Phelps K (2012) The spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician 86(6): 546-550.

- Koenig HG (2014) The Spiritual Care Team: Enabling the Practice of Whole Person Medicine. Religions 5(4): 1161-1174.

- Chen J, Lin Y, Yan J, Wu Y, Hu R (2018) The effects of spiritual care on quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness: A systematic review. Palliat Med 32(7): 1167-1179.

- Gordon BS, Keogh M, Davidson Z, Griffiths S, Sharma V, et al. (2018) Addressing spirituality during critical illness: A review of current literature. J Crit Care 45: 76-81.

- Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Gries CJ, Glavan B, Curtis JR (2007) Spiritual care of families in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 35(4): 1084-1090.

- Lichter DA (2013) Studies show spiritual care linked to better health outcomes. Health Prog 94(2): 62-66.

- Handzo G, Koenig HG (2004) Spiritual care: whose job is it anyway? South Med J 97(12): 1242-1244.

- Kannan S, Gowri S (2020) Spiritual Care: Define and Redefine Self. J Relig Health 59(1): 470-483.

- Christensen AR, Cook TE, Arnold RM (2018) How Should Clinicians Respond to Requests from Patients to Participate in Prayer? AMA J Ethics 20(7): E621-E629.

- Post SG, Puchalski CM, Larson DB (2000) Physicians and patient spirituality: professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Ann Intern Med 132(7): 578-583.

- Liefbroer AI, Olsman E, Ganzevoort RR, van Etten-Jamaludin FS (2017) Interfaith Spiritual Care: A Systematic Review. J Relig Health 56(5): 1776-1793.

- McManus K, Robinson PS (2020) A thematic analysis of the effects of compassion rounds on clinicians and the families of NICU patients. J Health Care Chaplain 28(1): 69-80.

- Underwood LG (2011) The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Overview and Results. Religions 2(1): 29-50.

- Thomas DR (2006) A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. American Journal of Evaluation. 27(2): 237-246.

- Klarsfeld A, Syed J, Mumtaz A (2021) An analysis of Religious Diversity Index (RDI) by Pew Research Center. In: Handbook on Diversity and Inclusion Indices. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/

- Bar-Sela G, Schultz MJ, Elshamy K, Rassouli M, Ben-Arye E, et al. (2019) Training for awareness of one’s own spirituality: A key factor in overcoming barriers to the provision of spiritual care to advanced cancer patients by doctors and nurses. Palliat Support Care 17(3): 345-352.

- Smyre CL, Tak HJ, Dang AP, Curlin FA, Yoon JD (2018) Physicians’ Opinions on Engaging Patients' Religious and Spiritual Concerns: A National Survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 55(3): 897-905.

- Luna MJ, Ameli R, Sinaii N, Cheringal J, Panahi S, et al. (2019) Gender Differences in Psycho-Social-Spiritual Healing. J Womens Health 28(11): 1513-1521.

- Meert KL, Thurston CS, Briller SH (2005) The spiritual needs of parents at the time of their child’s death in the pediatric intensive care unit and during bereavement: a qualitative study. Pediatr Crit Care Med 6(4): 420-427.

- Holston JT (2015) Supporting Families in Neonatal Loss: Relationships and Faith Key to Comfort. J Christ Nurs 32(1): 18.