Pulmonary Hypertension in Children with Esophageal Varices: Frequency and Relation to N-Terminal Pro B-Type Naturetic Peptide

Nagla H Abu Faddan1*, Duaa M Rafaat1, Tahra M K Sherif2 and Madleen AA Abdou2

1Department of Pediatrics, Assiut University, EgyptPocasset Family Dental, USA

2Department of Clinical Pathology, Assiut University, Egypt

Submission: September 14, 2016; Published: October 06, 2016

*Corresponding author: Nagla Hassan Abu Faddan MD. Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Assuit University, Assiut University Children Hospital, Assiut, Egypt, Post code: 71111, Tel:+20882368371; Fax:+20882368371; Emailnhi-af@hotmail.com

How to cite this article: Nagla H A F, Duaa M R, Tahra M K S, Madleen A. Pulmonary Hypertension in Children with Esophageal Varices: Frequency and 006 Relation to N-Terminal Pro B-Type Naturetic Peptide. Acad J Ped Neonatol. 2016; 1(5): 555573. DOI: 10.19080/AJPN.2016.01.555573

Abstract

Background:Portopulmonary hypertension (PPHTN) is a distinct pulmonary vascular complication of portal hypertension. There is no much information on PPHTN occurring in children. Detection of PPHTN at an early stage requires systematic screening at regular intervals by echocardiography (ECHO) in children with portal hypertension.

Aim of the work:to study the frequency of PPHTN in children attending Assiut University Children Hospital with esophageal and/ or fundal varices, to measure serum levels of Human N-Terminal Pro B-type Naturetic Peptide (NT-proBNP) and to evaluate its correlation with the occurrence of pulmonary hypertension in these children.

Patients and methods:This cross sectional study included 40 children with portal hypertension and 20 controls. All children with portal hypertension underwent Pulse oximetry and echocardiographic studies (ECHO). Serum levels NT-proBNP was measured in all cases and controls.

Results:6 (15%) were diagnosed as PPHTN. Dyspnea on exertion was detected in four children with PPHTN (66.7%), hypoxia was not detected in any of them. NT-proBNP was not significantly higher in children with portal hypertension than controls. There was no significant correlation between peak systolic pulmonary artery pressure (SPAP) and ALT, nor NT-proBNP. Circulating Levels of NT-proBNP did not correlate significantly with a right ventricular diameter or right ventricular anterior wall diameter.

Conclusion:Portal hypertension is an important risk factor of development of pulmonary hypertension in children. ECHO is a non invasive, safe and reliable screening method for children with PPHTN. Further researches are needed to evaluate the diagnostic and prognostic values of NT-proBNP in these children.

Keywords:Pulmonary hypertension; Children; Esophageal varices

Introduction

TThe vascular set of the liver is unique. The portal vein reaches the liver, where it branches into the liver sinusoids and comes out of the liver as hepatic veins which pours the blood into the inferior vena cava hence to the right atrium and right ventricle. From the right ventricle arises the pulmonary artery that carries the blood to the lungs. It can be therefore understood that rises in portal vein pressure, especially with the occurrence of portosystemic varices would lead to a secondary rise in the pulmonary arterial pressure. So that Portopulmonary hypertension (PPHTN) is a distinct pulmonary vascular complication of hepatic and extrahepatic portal hypertension in the absence of underlying cardiopulmonary disease [1-6]. The end result is a progressive remodelling of the wall of the small pulmonary arteries with vasoconstriction and thickening of the arterial wall resulting in a histopathological pattern of plexogenic arteriopathy. Because clinical symptoms are nonspecific and often subtle, a high index of suspicion for diagnosis is required [7]. PPHTN has chiefly been studied in adults [3]. There is not much information on PPHTN occurring in children; it has been reported in children with portal hypertension resulting from both cirrhosis and from congenital or acquired portal vein abnormalities. However, most reports deal with a small number of patients, and little is known of its prevalence and severity in children with liver disease [7,8]. Detection of PPHTN at an early stage requires systematic screening at regular intervals by echocardiography (ECHO) in children with portal hypertension. A careful ECHO surveillance of pulmonary artery pressure must be set up in such patients to allow early diagnosis and treatment of PPHTN. ECHO is the most widely used screening method for the detection of pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH). It provides a reasonably reliable and comprehensive assessment of the right heart and the pulmonary circulation [9].

Human N-Terminal Pro B- type Naturetic Peptide (NT-proBNP) is released from the ventricles in response to volume and pressure overload and serves as a noninvasive marker of right ventricular systolic impairment [10]. Recent attention has focused on these biomarkers as a potential screening tool for early pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) in high-risk populations [11].

Aim of the Work

To study the frequency of PPHTN in children attending Assiut university children’s hospital with esophageal and/ or fundal varices due to portal hypertension, to measure serum level of NT-proBNP and to evaluate its correlation with occurrence of pulmonary hypertension in these children.

Patients and Methods

This cross sectional study included 40 children with portal hypertension (24 males, 16 females) and 20 apparently healthy age and sex-matched children as a control group. Patients were consecutively recruited from pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy unit of Assiut university children hospital during the period from January 2013 to December 2015. The only inclusion criterion was the presence of portal hypertension diagnosed by endoscopic evidence of esophageal and/or gastric varices. All patients with histological evidence of cirrhosis, or Doppler ultrasonography evidence of portal vein thrombosis or cavernous transformation of the portal vein were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they had primary lung or heart disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome or spleen resection. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University, according to the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from participants’ parents/legal guardians. All studied children were subjected to full history taking through clinical examination, including age, gender, duration of illness, underlying diagnoses, causes of portal hypertension, prior complications and management of portal hypertension. Physical examinations were performed to evaluate for clinical evidence of portal hypertension and any clinical evidence of PAH.

Complete blood count measured using the CE11–DYN 3700 spectra–USA apparatus, liver function tests measured using a Synchron CX Pro auto-analyzer, Beckman Counter (Tokyo, Japan), prothrombin time and concentration and international normalized ratio (INR) were obtained. 3ml of venous blood samples were collected from patients and controls under standardized conditions in plain tubes were centrifuged (at 3000 g for 10min.) and serum samples were divided and stored in aliquots at – 20 °C until analyzed. Assay of serum levels of Human N-Terminal Pro B-type Naturetic Peptide (NT-proBNP) was performed using ELISA Kit (from WKEA Med Supplies-China catalog.No.WH- 219Lot No.20151119).

Pulse oximetry was used to screen for hypoxia in all patients. Arterial oxygen saturation (the amount of oxygenated hemoglobin in the blood) was recorded using a portable, battery powered pulse oximeter (Mini SPO2T manufactured by the Medair Hudiksvall, Sweden; Ref. LS1P- 9 Q) with the sensor device placed over the finger (index or middle) or the big toe. A reading that was stable for at least 3 minutes was noted down. Hypoxemia was defined as an arterial oxygen saturation of 90% recorded by pulse oximetry [12].

Evaluation for PPHTN

All children with portal hypertension underwent echocardiographic studies using M– mode, two dimensional, and Doppler techniques using commercially available phased array system employing a 4 and 7 MHZ transducer respectively (Magic bright 2, Vivid 3, Vingmed-Tech). Measurements were performed using the machine’s incorporate analysis package. Standard echo assessment was done using the standard parasternal view (longitudinal and transverse), apical view 4 and 5 chambers, also subcostal and suprasternal views.

On the echocardiography scan, special attention was given to

- Right ventricular Size This was measured in the m-mode parasternal short axis biventricular view [13].

- Interventricular septum. If there was a D shape in RV in parasternal short axis view [14].

- Hemodynamic assessment using Doppler echocardiography.

- Systolic pulmonary artery pressure (SPAP). Tricuspid regurge jet exceeding 2.5m/Sec considered significant. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure estimated from a peak tricuspid regurg velocity by a continuous wave Doppler using the modified Bernoulli equation to determine the RV systolic pressure. RVSP=SPAP=4(TRmax)2 + mean RA pressure (m RAP). A proper angulation and a sufficient envelope were taken in apical views [15].

- Diastolic pulmonary artery pressure. The diastolic pulmonary artery pressure (DPAP) was estimated from the velocity of the end-diastolic pulmonary regurgitant velocity using the modified Bernoulli equation: DPAP=4V (enddiastolic pulmonary regurgitation velocity square)2 + RA pressure [14].

- Mean pulmonary artery pressure. mPAP=4V (Early peak pulmonary regurgitation velocity)2 + RA pressure. This equation has been shown to correlate well with invasive measurements in adults and children [16].

The normal estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure (SPAP) is >35mmHg [17]. Mild PAH can be defined as an SPAP of approximately 36–50mmHg [18].

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were described by number and percent (N, %), while continuous variables were described by mean and standard deviation (Mean, SD and Median).

The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution, using Kolmogrove Smirnov test and Q-Q Plots. To compare between continuous variables t-test (parametric test) and Mann Whitney U test (non-parametric test) were used. Kruskal-Wallis H used for multiple comparisons. Pearson Correlation coefficient used to assess the association between continuous variables. A two-tailed p0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with the SPSS 20.0 software.

Results

Kruskal-Wallis H (nonparametric test) used to compare between all studied groups, Mann Whitney U (non parametric test) used to compare between each two groups).

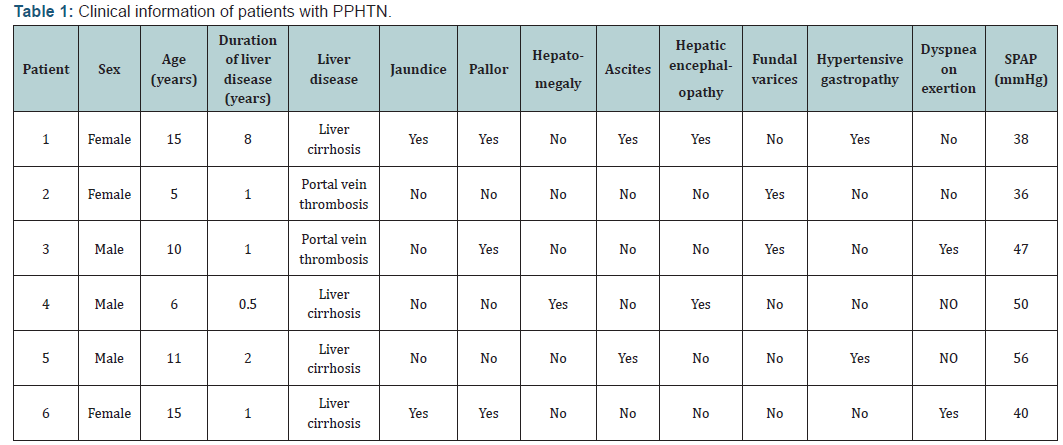

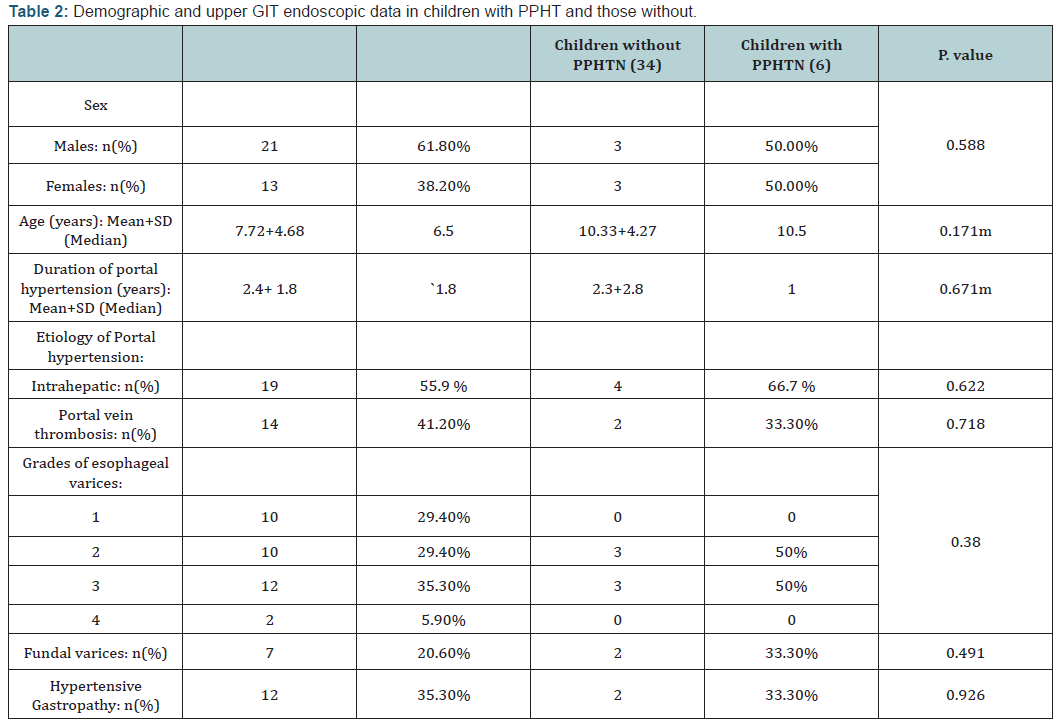

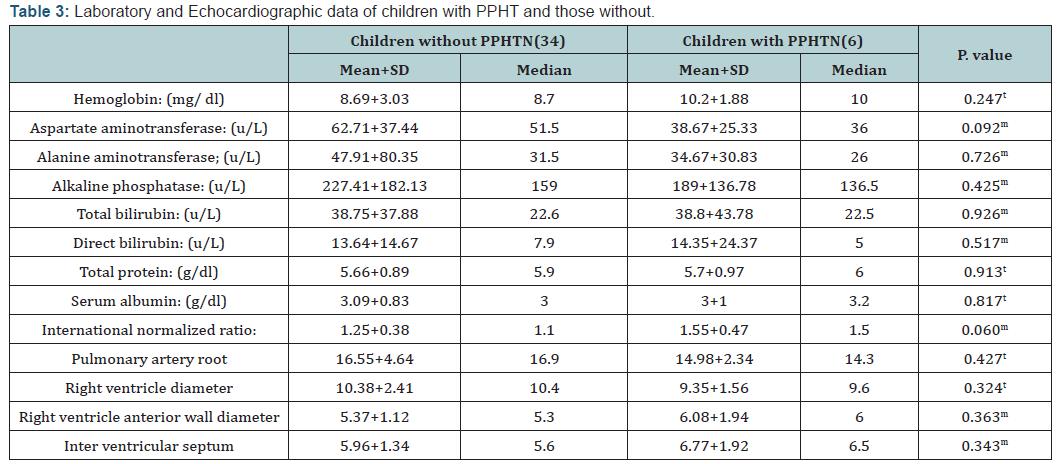

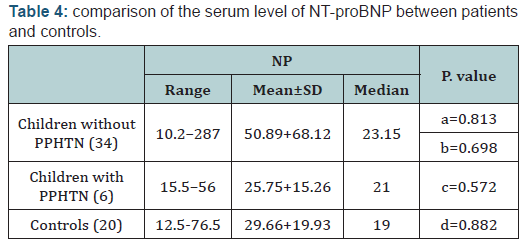

Among 40 children with portal hypertension included in this study, 6 (15%) were diagnosed as PPHTN (SPAP >35mmHg). Our results are shown in Tables 1-4. Regarding the clinical signs of pulmonary hypertension, dyspnea on exertion was detected in four children with PPHTN (66.7%), other clinical signs of PAH were not detected in any of them. Using pulse oximetry, hypoxia (arterial oxygen saturation of 90%) was not detected in any of children with PPHTN. The results of this study demonstrated that there is no statistically significant difference in serum levels of NT-proBNP between children with PPHTN and those without. In addition, circulating Levels of NT-proBNP did not correlate significantly with PSAP, right ventricular diameter or right ventricular anterior wall diameter (r=0.154; p=364), (r=0.192; p=0.236) and (r=0.093; p=0.567) respectively. Furthermore, there was no significant correlation between SPAP and ALT (r=0.1; p=0, 54)

Discussion

PPHNT is an important consequence of portosystemic shunting in children with chronic liver diseases or with extra hepatic portal vein obstruction/thrombosis. It is essential to be recognized early to prevent irreversible vascular remodelling [19]. Only small series of affected children have been reported and the incidence and clinical features of PPHTN in children have not been adequately described [20]. Out of 40 children included in this study, we report a series of 6 (15%) children with PPHTN. Our figure is higher than that reported by previous authors [7,8,19,21,22]. This difference may be due to the difference in the inclusion criteria between different studies or the difference in methods of PPHTN detection. In the present study, we included children with portal hypertension complicated with hematemesis due to esophageal and /or fundal varices, which may explain the high percentage of children with PPHTN in this study. Regarding screening of PPHTN, currently there is no accepted universal screening protocol for PPHTN in children with portal hypertension [7]. Although diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension is traditionally obtained by right heart catheterization (RHC) [23,24]; which is an invasive, risky procedure in small children and bleeding complications are a concern among patients with liver disease, other forms of diagnosis are preferred [20]. In the present study the children were screened by ECHO because it is non invasive, safe, reliable and previous studies reported that results of ECHO are comparable to RHC in patients with pulmonary hypertension [25,16]. Furthermore the European Respiratory Task Force’s recommended ECHO as a screening test for PPHTN [26]. The present study shows that there was no statistically significant difference between children with PPHTN and those without regarding demographic or laboratory data. These results are different from previous studies who reported that females [27] and low hemoglobin level [20] are risk factors, but agree with other study [28] who stated that the presence of portal hypertension and portosystemic shunts are thought to be the single most important factors determining the risk of development of pulmonary hypertension. Regarding the clinical pictures and severity of PPHTN in children included in this study, fortunately most cases (83.3%) with PPHTN diagnosed in this study were mild (PSAP 50mmHg). Furthermore, the clinical signs of pulmonary hypertension were not detected in our patients except dyspnea on exertion in four children with PPHTN (66.7%) which is a nonspecific symptom. Hypoxia was not detected in any of them. In the present study, we screened for hypoxia using pulse oximetry because of its non-invasive nature in order to avoid obtaining arterial blood gas measurements because of ethical consideration and previous studies reported that SaO2 by pulse oximetry is an appropriate alternative to arterial blood gas measurements to screen children with portal hypertension [21]. In the present study only one child (16.7%) had SPAP 56mmHg; interestingly he did not have any clinical sign of PAH. Because our policy is avoiding invasive procedure in these children unless they will achieve a great benefit and this child is already suffering from chronic liver affection, we avoided the idea of doing RHC to this child.

The results of the present study showed that there was no significant correlation between PSPA with liver function. These results are in agreement with previous study [20] however, these results are based on small number of cases and large studies are required to verify this correlation.

NT-proBNP are cardiac biomarkers released by myocytes in response to ventricular wall stress due to pressure overload and volume expansion [29,30]. The value of these biomarkers in the diagnostic approach of PAH has already been investigated in adults, with promising results. In some studies, there is increasing evidence that NT-proBNP may be a useful marker for right ventricular dysfunction and predict outcome in patients with PAH [31,32]. Circulating levels of NT-proBNP correlate with mPAP [33]. While in others there is not enough evidence to rely on BNP as a diagnostic marker of patients with PAH [34]. Pediatric studies are still scarce [27]. The results of this study demonstrated that NT-proBNP was not significantly higher in children with PPHTN than those without. Furthermore, circulating Levels of NT-proBNP did not correlate significantly with PSPA. Casserly et al. [32] reported that elevations in NT-proBNP levels are usually not seen until pulmonary artery pressure is high enough to cause right ventricular strain. In this study, all cases with PPHTN diagnosed were mild and this may explain the absence of significant elevation of circulating levels of NT-proBNP in children with PPHTN than those without. The usefulness of these biomarkers in clinical care is also still a debate, some authors stated that these biomarkers do not replace the clinical parameters, but may provide additional information [35]. Others reported that both baseline levels of plasma BNP and its increase during a 3-month follow-up period are strong independent prognostic factors in patients with PAH [36]. So, further research would be needed to assess the diagnostic and prognostic values of the biomarkers. Finally, important issues regarding screening and management of PPHTN in children remain unanswered. There are no controlled, prospective studies that have addressed the question of which medications are most efficacious and safe in PPHTN patients. Whether liver transplantation should be used for treating a child with PPHTN complicating or whether PPHTN should be treated by pulmonary vasodilators remains open to discussion [8,37].

Conclusion

Portal hypertension is an important risk factor of development of pulmonary hypertension in children. ECHO is a non invasive, safe and reliable screening method for children with PPHTN. Further researches are needed to evaluate the diagnostic and prognostic values of NT-proBNP in these children.

Funding

Available resources of Assiut University.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interests.

- All authors declare that the submitted version of this paper is original and is not under simultaneous consideration for publication elsewhere and tables in this study did not reproduced from another source.

- All authors have seen and agreed to the submitted version of the paper in this journal

- All Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest and source of funding is the available resources of Assiut University.

- This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Assuit University according to the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from participant’s parent/legal guardian.

- Rodriguez-Roisin R, Krowka MJ, Herve P, Fallon MB (2004) Pulmonaryhepatic vascular disorders (PHD). Eur Respir J 24(5): 860- 880.

- Porres-Aguilar M, Altamirano JT, Torre-Delgadillo A, Charlton MR, Duarte-Rojo A (2012) Portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome: a clinician-oriented overview. Eur Respir Rev 21(125): 223-233.

- Cartin-Ceba R, Krowka MJ (2014) Portopulmonary hypertension. Clin Liver Dis 18(2): 421-438.

- Porres-Aguilar M, Zuckerman MJ, Figueroa-Casas JB, Krowka MJ (2008) Portopulmonary hypertension: state of the art. Ann Hepatol 7(4): 321- 330.

- Krowka MJ (2004) Portopulmonary Hypertension: Understanding Pulmonary Hypertension in the Setting of Liver Disease. Pulmonary Hypertension Association: Advances in Pulmonary Hypertension 3: 4-8.

- Hoeper MM, Krowka MJ, Strassburg CP (2004) Portopulmonary hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome. The Lancet 363(9419): 1461-1468.

- Condino AA, Ivy DD, O’Connor JA, Narkewicz MR, Mengshol S, et al. (2005) Portopulmonary hypertension in pediatric patients. Pediatr 147(1): 20-26.

- Ecochard-Dugelay E, Lambert V, Schleich JM, Duche M, Jacquemin E, et al. (2015) Portopulmonary Hypertension in Liver Disease Presenting in Childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 61(3): 346-356.

- Milan A, Magnino C, Veglio F (2010) Echocardiographic indexes for the non-invasive evaluation of pulmonary hemodynamics. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 23(3): 225-239.

- Blyth KG, Groenning BA, Mark PB, Martin TN, Foster JE, et al. (2007) Nt-probnp can be used to detect right ventricular systolic dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 29(4): 737-744.

- Lau EM, Manes A, Celermajer DS, Galiè N (2011) Early detection of pulmonary vascular disease in pulmonary arterial hypertension: time to move forward. Eur Heart J 32(20): 2489-2498.

- Basnet S, Adhikari RK, Gurung CK (2006) Hypoxemia in Children with Pneumonia and Its Clinical Predictors. Indian J Pediatr 73(9): 777-781.

- Kassem E, Hump lT, Friedberg MK (2013) Prognostic significance of 2-dimensional, M mode, and Doppler echo indices of right ventricular function in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am Heart J 165(6): 1024-1031.

- Jone PN, Ivy DD (2014) Echocardiography in pediatric pulmonary hypertension. Front Pediatr 12(2): 124.

- Hatle L, Angelsen BA, Tromsdal A (1981) Non-invasive estimation of pulmonary artery systolic pressure with Dopplerultrasound. Br Heart J 45(2): 157-165.

- Abbas AE, Fortuin FD, Schiller NB, Appleton CP, Moreno CA, et al. (2003) A simple method for non invasive estimation of pulmonary vascular resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol 41(6): 1021-1027.

- https:/McQuillan BM, Picard MH, Leavitt M, Weyman AE (2001) Clinical correlates and reference intervals for pulmonary artery systolic pressure among echocardiographically normal subjects. Circulation 104(23): 2797-2802.

- Galiè N, Torbicki A, Barst R, Dartevelle P, Haworth S, et al. (2004) Guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. The Task Force on Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 25(24): 2243-2278.

- Sokol RJ (2015) Portopulmonary hypertension: opportunities for precision pediatrics. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 61(3): 268-269.

- Chen HS, Xing SR, Xu WG, Yang F, Qi XL, et al. (2013) Portopulmonary hypertension in cirrhotic patients: Prevalence, clinical features and risk factors. Exp Ther Med 5(3): 819-824.

- Whitworth JR, Ivy DD, Gralla J, Narkewicz MR, Sokol RJ (2009) Pulmonary vascular complications in asymptomatic children with portal hypertension. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 49(5): 607-612.

- Bernard O, Franchi-Abella S, Branchereau S, Pariente D, Gauthier F, et al. (2013) Congenital portosystemic shunts in children: recognition, evaluation and management. Semin Liver Dis 32(4): 273-287.

- Krowka MJ (2006) Evolving dilemmas and management of portopul¬monary hypertension. Semin Liver Dis 26(3): 265-272.

- Golbin JM and Krowka MJ (2007) Portopulmonary hypertension. Clin Chest Med 28(1): 203-218.

- Scapellato F, Temporelli PL, Eleuteri E, Corrà U, Imparato A, et al. (2001) Accurate noninvasive estimation of pulmonary vascular resistance by Doppler echocardiography in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 37(7): 1813-1819.

- Rodríguez-Roisin R, Krowka MJ, Hervé P, Fallon MB; ERS Task Force Pulmonary-Hepatic Vascular Disorders (PHD) Scientific Committee (2004) pulmonary-hepatic vascular disorders. Eur Respir J 24(5): 861- 880.

- Kawut SM, Krowka MJ, Trotter JF, Roberts KE, Benza RL, et al. (2008) Clinical risk factors for portopulmonary hypertension. Hepatology 48(1): 196-203.

- Anikethana GV, Ravikumar TN, Chethan KKL (2014) Study Of Portopumonary hypertension in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J of Evidence Based Med & Hlthcare 1(7): 518-528.

- Levin ER, Gardner DG, Samson WK (1998) Natriuretic peptides. N Engl J Med 339(5): 321-328.

- Cracowski JL, Leuchte HH (2012) The potential of biomarkers in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol 110(6 Suppl): 32S-38S.

- Lammers AE, Hislop AA, Haworth SG (2009) Prognostic value of B-type natriuretic peptide in children with pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 135(1): 21-26.

- Casserly B, KlingerJR (2009) Brain natriuretic peptide in pulmonary arterial hypertension: biomarker and potential therapeutic agent. Drug Des Devel Ther 3: 269-287.

- Nagaya N, Nishikimi T, Okano Y, Uematsu M, Satoh T, et al. (1998) Plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels increase in proportion to the extent of right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 31(1): 202-208.

- Ten Kate CA, Tibboel D, Kraemer US (3) B-type natriuretic peptide as a parameter for pulmonary hypertension in children. A systematic review. Eur J Pediatr 174(10): 1267-1275.

- Takatsuki S, Wagner BD, Ivy DD (2012) B-type natriuretic peptide and amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide in pediatric patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Congenit Heart Dis 7(3): 259- 267.

- Nagaya N, Nishikimi T, Uematsu M, Satoh T, Kyotani S, et al. (2000) Plasma brain natriuretic peptide as a prognostic indicator in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 102(8): 865-870.

- Whitworth JR, Sokol RJ (2005) Hepato-portopulmonary disorders -- not just in adults! J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 41(4): 393-395.

Author’s Contributions

DR Nagla Abu Faddan who collect the scientific data for this study and write the manuscript, Dr Duaa Rafaat, who perform the Echo examination for all children. Dr Tahra and Dr Madleen who perform the laboratory work in this study.