Abstract

Control of the genome has been revolutionized through epigenetic engineering, and the field stands out as a means of controlling gene expression with the best possible precision, reversibility, and programmability. It does so by changing chromatin states, but not permanently the DNA sequence, so continues to be an important tool in making safe the potential of increasing irreversible mutagenesis effectiveness in both personalized medicine and synthetic biology. This technique relies on the principle of epigenetic switches made of DNA targeting programmable proteins (including deactivated Cas9 (dCas9)) and Zinc Finger domains which can switch epigenetic marks on or off having a subsequent outcome of stable and tunable gene expression. It is demonstrated by the evolutionary utility of this type of mechanism by studying Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which has provided cells with the ability to rapidly switch the epigenome, thereby allowing them to survive changes in their environment without having to alter their genome. Modular CRISPR has enabled dCas9 systems to target various mammalian targets such as BACH2, HNF1A, IL6ST, and MGAT3 that caused persistent transcriptional programs extending to 30 days post-delivery of the genetic material. In addition, alterations on dCas9, fusion protein versions have not only led to a precise range of tools, but also an increase in biosafety due to a significant reduction in off, target effects.

This is ultimately followed by the convergence of finely, tuned epigenetic switches and the synthetic biology, leading to a safer, more precise, and diverse process of disease modeling as well as the therapeutic intervention.

Keywords:Epigenetic Engineering; CRISPR/dCas9; Programmable Gene Regulation; Epigenetic Switching; Personalized medicine.

Abbreviations: CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; dCas9: Deactivated Cas9; sgRNA: Single Guide; RNA ZFNs: Zinc Finger Nucleases; TALEs: Transcription Activator-Like Effectors; TALENs: Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases; DNMT: DNA Methyltransferase; TET1: Ten-Eleven Translocation 1; KRAB: Krüppel-Associated Box; LSD1: Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1; DSBs: Double- Strand Breaks; CpG: Cytosine-phosphate-Guanine

Introduction

During much of its history, the central dogma of molecular biology has truly associated cellular functionality with DNA sequence. Epigenetics fundamentally changed the concept by demonstrating that the changes in gene expression, potentially subject to inheritance, do not require any alterations in the sequence of the DNA [1]. Genetic genome editing other systems including Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), TALENs, as well as the earliest, generation CRISPR, Cas9 systems largely depend on creating double, strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA to modify genetic material [2]. However, these nucleolytic methods involve an extremely high probability of irreversible mutagenesis thus being automatically limited by the dynamic reversibility of safe therapeutic protocols [3]. Another approach in epigenetics, which is a leading and edge, involves the application of deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) and other programmable DNA, binding modules along with chromatin, modifying enzymes. This specificity is very high with such complexes being able to be targeted to the desired genomic locations precisely [4]. These instruments regulate gene expression either by suppressing or activating genes by changing the methylation of DNA or the buildings of histones, being epigenetic switches [5]. Therefore, this is a highly significant attribute to the future of genome editing that will no longer be the case of gene fixes but will be concerned with the gene regulatory networks that are not only intricate but can also be dynamically and temporarily governed [6].

The present article provides a critical evaluation of the potential of epigenetic switches, in which the evolution of synthetic biology constructs into clinical instruments that are ready to use in personalized medicine is analyzed. Examples of the programmable regulatory mechanisms and evolutionary foundation of epigenetic switching based upon research into the model organism such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and implementation of these systems to develop the precise and safe therapeutic intervention to human diseases are also discussed [7, 8].

Methodology and Literature Search Strategy

Subsequent to the above guideline, a systematic search was carried out to find the literature that is relevant to the topic and published from January 2013 to January 2026. The search encompassed leading scientific databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and the MDPI library.

The search strategy used the following inclusion criteria:

• Keywords: Main search terms were “Epigenetic

engineering,” “CRISPR, dCas9, ““Epigenetic Switches, “ “Synthetic

Biology, “ “DNA Methylation Editing, “ and “Personalized Medicine.”

• Article Type: Open Access review articles, high, impact

original research papers, and recent proceedings reporting novel

epigenetic editing tools or clinical applications were preferred.

• Relevance: The selection of the papers was made

considering the focus on programmable gene regulation (dCas9,

TALE, ZFP) as opposed to general epigenetics.

Data from these studies were combined to identify the improvements in three different categories: (1) Mechanisms of synthetic switching, (2) Applications in disease modeling, and (3) Clinical translation and biosafety. Such an organized method makes it possible to review thoroughly how epigenetic engineering is moving from being a concept in biology to a real medical treatment.

Results: Mechanisms and Advances in Epigenetic Switches

Evolution of Programmable DNA-Binding Domains

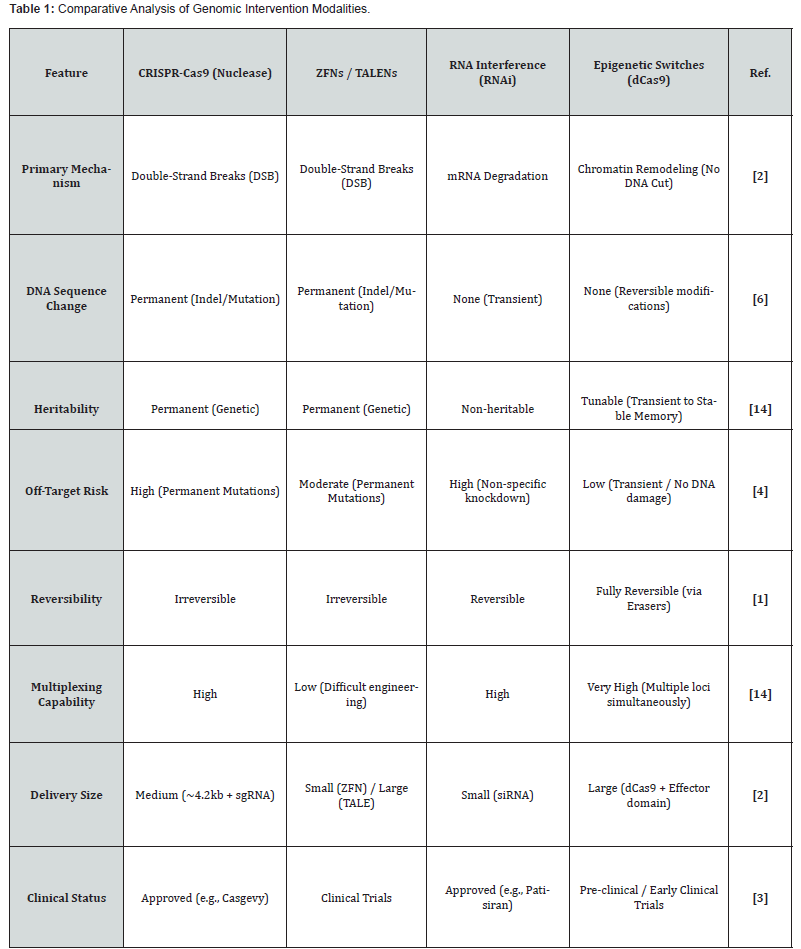

The literature review makes it evident that there is a chronological trend in the “homing devices” that are employed for epigenetic switches. The initial research makes use of Zinc Finger Proteins (ZFPs), which identify 3, 4 base pairs per module. Although they work well, they are chemically very complicated to produce for new targets [9, 10]. Subsequently, TALEs (Transcription Activator, Like Effectors) were introduced, which granted higher specificity but were still very labor, intensive to clone [11, 12]. The major breakthrough happened when CRISPR, dCas9 was introduced. In contrast to the earlier methods, dCas9 is directed by a short RNA sequence (sgRNA), which allows it to be very programmable and modular [13, 14]. A comparison of these methods clearly shows the reasons for which dCas9 has become the go, to tool for epigenetic engineering (Table 1).

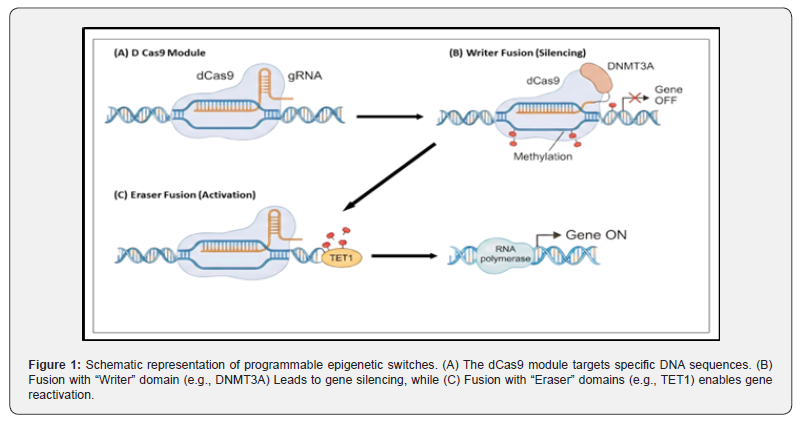

Synthetic Biology: The “Writer” and “Eraser” Toolkit

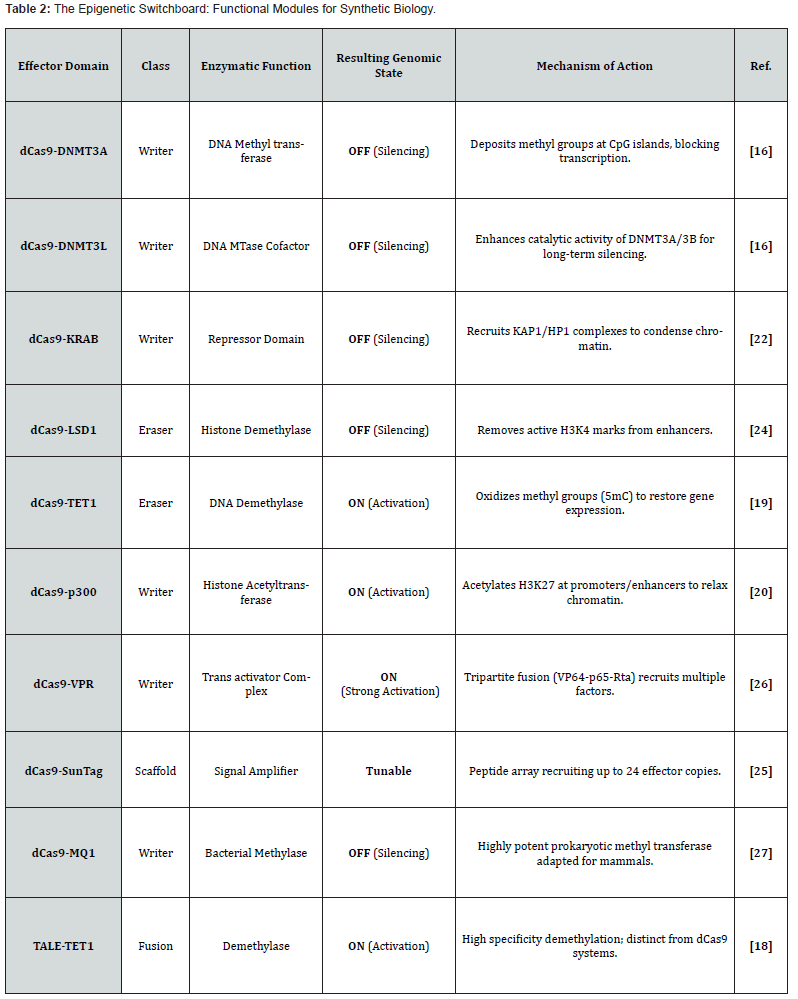

To realize a functional switch, dCas9 has to be connected with catalytic domains that can “write” or “erase” epigenetic marks [15]. It has been shown that fusions with DNMT3A or DNMT3L can be used to place methyl groups at CpG islands, thereby silencing genes [16, 17]. On the other hand, TET1 fusions lead to demethylation thus reactivating tumor suppressors that have been silenced [18, 19]. Furthermore, histone modifications are also altered; dCas9, p300 acetylates histone H3K27 in order to activate enhancers [20, 21] whereas dCas9, KRAB recruits heterochromatin machinery for silencing [22, 23]. A variety of “switchboard” effector domains that can be used in synthetic biology are listed in (Table 2).

Modularity and Heritability

One of the key findings in recent literature is the emergence of “second, generation” systems (e.g., SunTag, SAM) that magnify these signals [25, 26].Importantly, a handful of works that have targeted loci BACH2, HNF1A, IL6ST, and MGAT3 have shown that these changes are capable of inducing “epigenetic memory, “ thus the transcriptional consequence is still maintained even 30 days post, transfection [28, 29].Such a transmission of the induced state resembles the behavior of natural biological switches in S. cerevisiae whereby the epigenetic state is preserved to cope with environmental stress without a genetic mutation [30, 31].

Discussion: Implications for Personalized Medicine

Precision Therapy

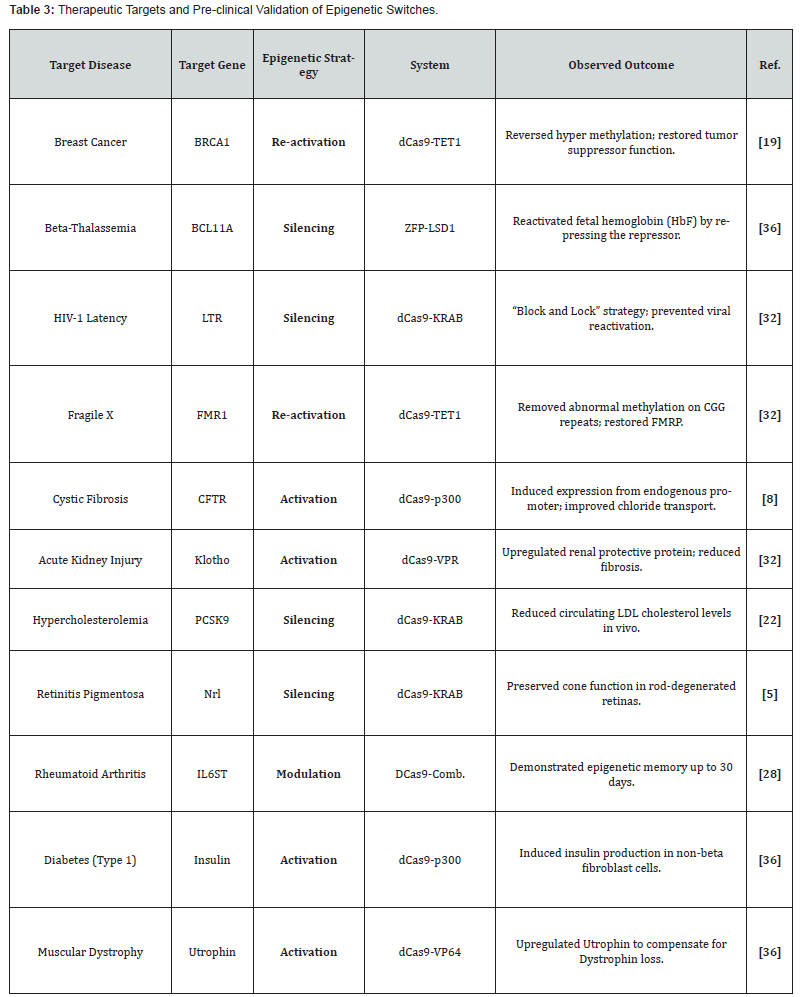

Correcting gene expression that is dysregulated without changing the DNA sequence is a safer way of personalized medicine [32]. Several studies are emphasizing on “epigenetic therapy” for cancer, whereby hyper methylated tumor suppressor genes can be selectively reactivated [33, 34]. Such a strategy is free from the potential dangers of off, target mutagenesis resulting from the use of active Cas9 nucleases [35]. (Table 3) summarizes various diseases in which these epigenetic switches have shown therapeutic effectiveness in animal models (Figure 1).

Challenges and Biosafety

Nevertheless, there are still difficulties after the promise. The research articles point out the “off, target” epigenetic changes as one of the main issues [37]. However, optimization of dCas9 fusion proteins over the last several years has shown that the off, target activity is greatly reduced, which in turn raises the biosafety profile [38, 27]. In addition, the reversibility of the epigenetic changes is an extra safety feature that is not there in case of permanent gene editing [39, 40].

Conclusion

Epigenetic engineering is fundamentally changing the way we think about genome modification. Rather than being tied to changes in the DNA sequence, it provides a precision, programmable and reversible way of controlling genes. Incorporating high, resolution epigenetic switches with synthetic biology concepts is dramatically enhancing our capability to fix the gene networks that are out of regulation. The advent of personalized medicine will see these tools becoming a necessity for handling complicated diseases, thus, presenting treatments that are not only really effective but substantially safer at their core as compared to the mutagenic ones that came before them. In order to fully unlock the clinical potential of this technology, future research has to be geared towards figuring out the delivery of vectors and the long, term stability of epigenetic states that are induced.

References

- JurkowskiTP, Ravichandran M, Stepper P (2015) Synthetic epigenetics-towards intelligent control of epigenetic states and cell identity. Clin Epigenet 7 (1): 18.

- Gaj T, Gersbach, CA, Barbas CF (2013) ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol 31 (7): 397-405.

- Uddin F, Rudin C M, Sen T (2020) CRISPR Gene Therapy: Applications, Limitations, and Implications for the Future. Front. Oncol 10: 1387.

- Qi LS, Larson MH, Gilbert LA, Doudna JA, Weissman JS et al. (2013) Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-Guided Platform for Sequence-Specific Control of Gene Expression. Cell 152 (5): 1173-1183.

- Rajanala K, Upadhyay A (2024) Epigenetic Switches in Retinal Homeostasis and Target for Drug Development. Int J Mol Sci 25(5): 2840.

- Adli M (2018) The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nat Commun 9(1): 1911.

- Kolàřová J, Ehrlich M (2022) Epigenetic Editing: A New Horizon in Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 23(13): 7869

- Mlambo T, Nitzsche B, Wirth T (2022) Epigenetic Editing: The Potential of CRISPR/Cas9 for the Treatment of Human Diseases. Cells 11(22): 3564.

- Beerli RR, Barbas CF (2002) Engineering polydactyl zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat Biotechnol 20(2): 135-141.

- Maeder ML, Thibodeau Beganny S, Osiak A, Wright DA, Anthony RM, et al. (2008) Rapid "open-source" engineering of customized zinc-finger nucleases for highly efficient gene modification. Mol Cell 31(2): 294-301.

- Zhang F, Cong L, Lodato S, Kosuri S, Church GM, et al. (2011) Efficient construction of sequence-specific TAL effectors for modulating mammalian transcription. Nat Biotechnol 29(2): 149-153.

- Boch J, Scholze H, Schornack S, Landgraf A, Hahn S, et al. (2009) Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-type III effectors. Science 326(5959): 1509-1512.

- Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Adamson B, Villalta JE, Chen Y, et.al. (2014) Genome-Scale CRISPR-Mediated Control of Gene Repression and Activation. Cell 159(3): 647-661.

- Dominguez AA, Lim WA, Qi LS (2016) Beyond editing: repurposing CRISPR-Cas9 for precision genome regulation and interrogation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17(1): 5-15.

- Park M, Patel N, Keung AJ, Khalil AS (2019) Engineering epigenetic regulation using synthetic biology. Philos. Trans R Soc B 374: 20180445.

- Liu XS, Wu H, Ji X, Stelzer Y, Wu X, et al. (2016) Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome. Cell 167(1): 233-247.

- Vojta A, Dobrinić P, Tadić V, Bočkor L, Korać P, et al. (2016) Repurposing the CRISPR-Cas9 system for targeted DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res 44(12): 5615-5628.

- Maeder ML, Anger M, Davies B, Lattanzi A (2013) Targeted DNA demethylation and activation of endogenous genes using programmable TALE-TET1 fusion proteins. Nat Biotechnol 31(12): 1137-1142.

- Choudhury SR, Cu Y, Lubecka K, Stefanska B, Irudayaraj J (2016) CRISPR-dCas9 mediated TET1 targeting for selective DNA demethylation at BRCA1 promoter. Oncotarget 7(29): 46545-46556.

- Hilton IB, D'Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, Thakore PI, Crawford GE, et al. (2015) Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat Biotechnol 33(5): 510-517.

- Perez-Pinera P, Kocak DD, Vockley CM, Adler AF, Kabadi AM, et al. (2013) RNA-guided gene activation by CRISPR-Cas9-based transcription factors. Nat Methods 10(10): 973-976.

- Thakore PI, D'Ippolito AM, Song L, Safi A, Shivakumar NK, et al. (2015) Highly specific epigenome editing by CRISPR-Cas9 repressors for silencing of distal regulatory elements. Nat Methods 12(12): 1143-1149.

- Yeo NC, Chavez A, Lance-Byrne A, Chan Yk, Menn D, et al. (2018) An enhanced CRISPR repressor for targeted mammalian gene regulation. Nat. Methods 15 (8): 611-616.

- Kearns NA, Genga RM, Enuameh MS, Garber M, Wolfe SA, et al. (2014) Cas9 effector-mediated regulation of transcription and differentiation in human pluripotent stem cells. Development 141(1): 219-223.

- Tanenbaum ME, Gilbert LA, Qi LS, Weissman JS, Vale RD (2014) A protein-tagging system for signal amplification in gene expression and fluorescence imaging. Cell 159(3): 635-646.

- Konermann S, Brigham MD, Trevino AE, Joung J, Abudayyeh O, et al. (2015) Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature 517 (7536): 583-588.

- Goell J, Hilton IB (2021) CRISPR/Cas9-based epigenome editing for research and therapy. Trends Biotechnol 39: 645-646.

- Amabile A, Migliara A, Capasso P, Biffi M, Cittaro D, et al. (2016) Inheritable Silencing of Endogenous Genes by Hit-and-Run Targeted Epigenetic Editing. Cell 167(1): 219-232.

- Nuñez JK, Chen J, Pommier GC, Cogan JZ, Replogle JM, et al. (2021) Genome-wide programmable transcriptional memory by CRISPR-based epigenome editing. Cell 184(10): 2503-2519.

- Acar M Mettetal JT, van Oudenaarden A (2008) Stochastic switching as a survival strategy in fluctuating environments. Nat Genet 40(4): 471-475.

- Bintu L, Yong J, Antebi YE, McCue K, Kazuki Y, et al. (2016) Dynamics of epigenetic regulation at the single-cell level. Science 351(6274): 720-724.

- Breuer GA, Earley EJ, Saxena T, Park M, Păun O, et al. (2021) Designing the Epigenome: A Review of the Current State of Epigenetic Editing. Front Genet 12: 765733.

- Jones PA, Baylin SB (2002) The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 3(6): 415-428.

- Saunderson EA, Enciso J, Gribben JG (2017) Epigenetic editing: a new toolkit for dissecting and treating cancer. Blood 130: 2366-2367.

- Komor AC, Badran AH, Liu DR (2017) CRISPR-based technologies for the manipulation of eukaryotic genomes. Cell 168(1-2): 20-36.

- Boudadi E, Stower H (2020) CRISPR/Cas9-based epigenome editing: A new era for disease therapy Mol Ther. Nucleic Acids 22: 57-65.

- Tycko J, Myer V E, Hsu PD (2016) Methods for specificity profiling of genome editing nucleases. Mol Cell 63(3): 355-370.

- Pulecio J, Verma N, Mejía-Ramírez E, Huangfu D, Raya A (2017) CRISPR/Cas9-based engineering of the epigenome. Cell Stem Cell 21(4): 431-447.

- Cano-Rodriguez D, Gjaltema RA, Juenemann S, Sasikumar P, Zwart W, et al. (2016) Writing of H3K4me3 overcomes epigenetic silencing in a sustained but not heritable manner 7: 12284.

- Kungulovski G, Jeltsch A (2015) Epigenome editing: state of the art, concepts, and perspectives. Trends Genet 32(2): 101-113.